Spiral City

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York

While Mexico City has been intermittently a progressive and modern city with a cosmopolitan culture, it has been equally notorious for state-, military-, and narcotic-related violence and corruption, along with sharp class distinctions. On September 19, 1985, one of the country’s most devastating earthquakes occurred in the city. Hundreds of buildings fell, and thousands of lives were lost. Whole neighborhoods in the center lay abandoned, and distrust in the government was rampant, a condition that was exacerbated in the years that followed, as in 1994, when Mexico entered into the North American Free Trade Agreement with the United States and Canada, widely considered at the time to be serving only the elite. Against this backdrop, however, something of a renaissance took place in the 1990s, with sudden attention being paid to the city by contemporary artists. In the wake of another devastating earthquake in 2017, occurring thirty-two years to the day after the 1985 tragedy, it’s instructive to look back at a formative period of Mexico City’s role in today’s globalized art market and at the work of artists who impacted the continuing image of the metropolis as precarious and creative in equal measure.

Among the markers of this shift was the arrival of European artists—including Francis Alÿs, Santiago Sierra, and Melanie Smith—who chose Mexico as a place where they could work outside the confines of the established art circuit. Alongside a number of Mexican artists—Miguel Calderón, Silvia Gruner, Yoshua Okón, and Gabriel Orozco, to name but a few—these contemporaries frequently used the social milieu as a studio in which to enact performances, interventions, and works of assemblage from and amidst the prolific detritus that could be found in the streets and markets. Hostile bureaucracy butting up against the anarchic informality of street life became the physical backdrop and sounding board for their practices. For many, the Zócalo, Mexico City’s edgy and dilapidated historic center, particularly around the Calle Licenciado Verdad, provided both constant stimulus and affordable rent and, in turn, became a place where artist-run galleries emerged, as documented in Daniel Montero’s 2014 exploration of a pivotal moment in contemporary art—and the emergence of a critical debate on Mexico’s increasingly significant position in a global market—El cubo de Rubik, arte mexicano en los años 90 (The Rubik’s Cube: Mexican art in the ’90s). Others colonized the Condesa area, opening exhibition spaces such as La Panaderia in the then run-down neighborhood that has since been gentrified.

© the artist and courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York

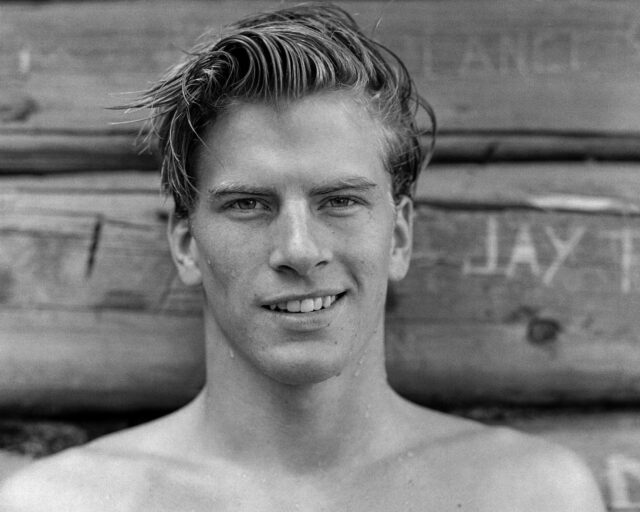

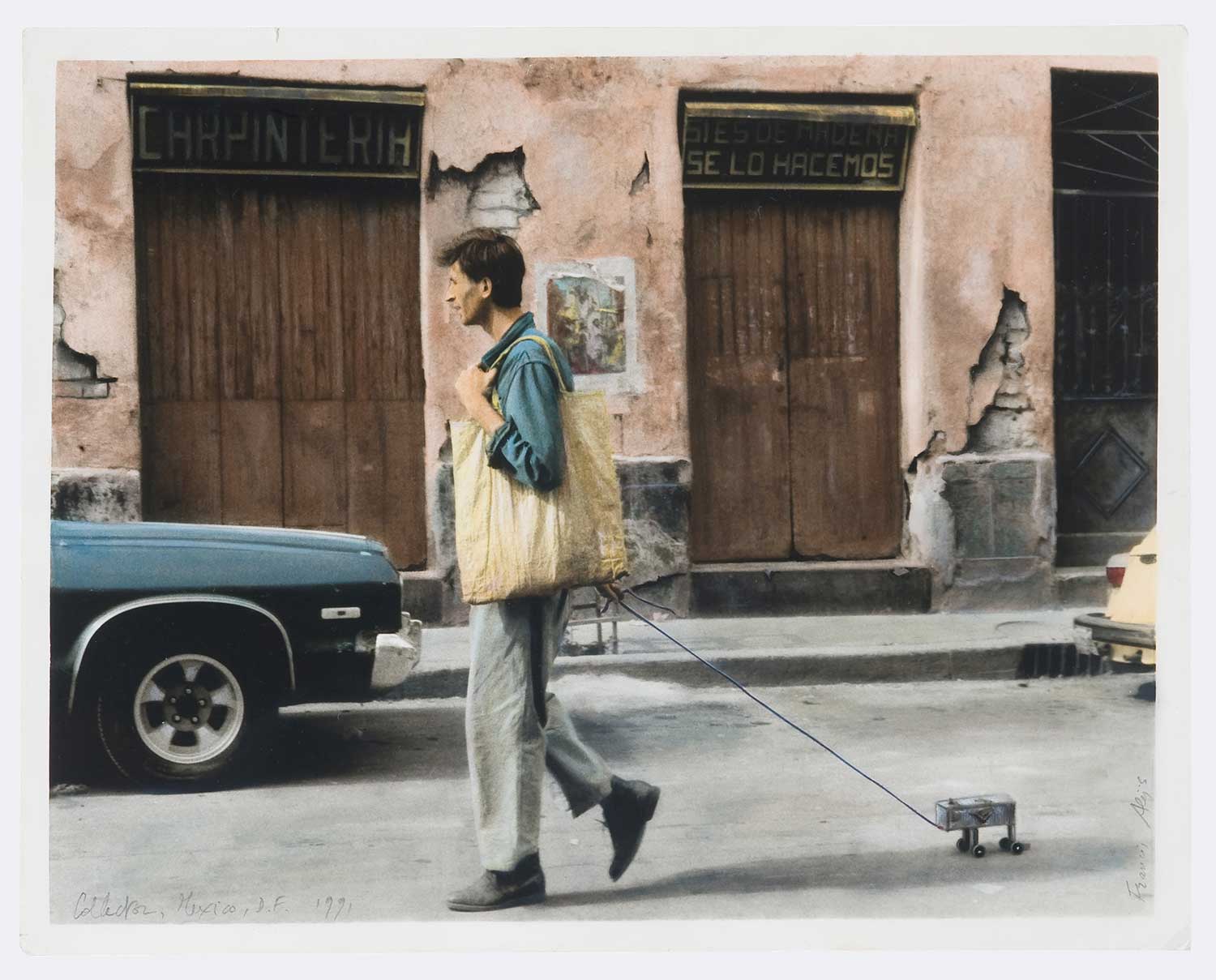

Mexico City street life displays both petty freedoms and ad hoc systems. For these transplanted artists, one might consider it a mise-en-scène, but something of a partial one, alongside the stereotyped images of the megalopolis. Trained as an architect, Belgian artist Francis Alÿs arrived as part of a humanitarian project to aid reconstruction following the 1985 earthquake. In his earlier artwork, Alÿs had developed distinctive, poetic, and personal investigations of a city’s flows and ambiences more than its physical environments. This approach lent itself to an artistic practice that coalesced in Mexico, where he chose to remain. Alÿs’s walking excursions through the dilapidated city center saw him tapping into its own sometimes languid, sometimes staccato rhythms. Activities such as pushing a block of ice through the streets until it melted into nothingness or wearing a magnetic pair of shoes that attracted nails, bottle tops, and other discarded shrapnel of the comings and goings of the city’s inhabitants were among his strategies. Often derived from observation of everyday activities, they presented an appropriation of psychogeographical methods in a “third-world” context. In his meanderings, Alÿs was especially drawn to the contrast of modern and premodern found in the urban fabric, which he described as paradoxically existing in the Zócalo, around which many of these works were made. As he has described it: “Does it matter even if or up to which point this modernity has really been lived here . . . ? What matters today is just the memory of it, fictitious or real. . . . All the ingredients of modernity may be there, but the city often continues to function on the basis of a pre-modern parallel economy.”

Whether Alÿs was reenacting and reframing the overlooked quotidian aspects of people’s routines and labors or commissioning premodern laborers to copy his own paintings, his images and actions accrued their potency from the city itself. Alÿs’s works also avoided a singular definition: photographic documentation of his performances was presented in the gallery, alongside video and drawings, while reproduced images on postcards, with short didactic texts adopting the style of Conceptual art, were intended to be distributed beyond its confines. As philosopher Jacques Rancière writes, the aesthetic revolution of modern times “shifts the focus from great names and events to the life of the anonymous; it finds symptoms of an epoch, a society, or a civilization in the minute details of ordinary life.” Alÿs and his contemporaries created their own exceptional moments that circulated within the ordinary.

© the artist and courtesy Lisson Gallery, London

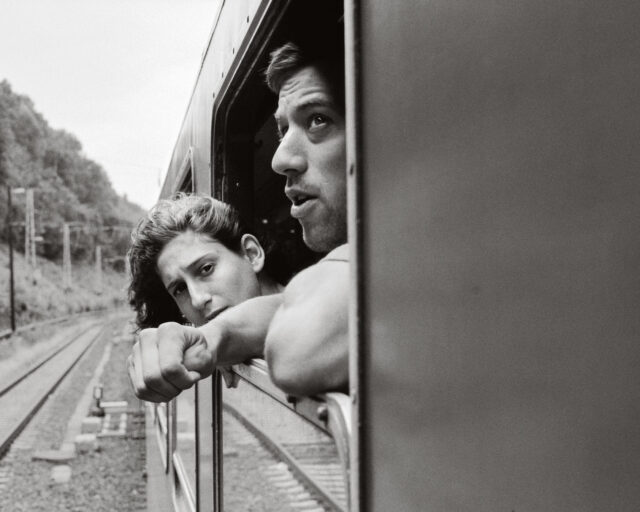

The Spanish artist Santiago Sierra took a more antagonistic approach to the city’s movements of traffic and people. Simply documented in black-and-white photographs and video, his piece Obstruction of a Freeway with a Truck’s Trailer, Anillo Perférico Sur, Mexico City, Mexico. November 1998 (1998) appears to depict an unusual, quasi-criminal action. Sierra refers to the work in terms that blur sociopolitical and Minimalist aesthetics, stating that it “consisted of positioning a white prism perpendicular to the road, generating a traffic jam.’’ As the artist also noted, “the driver didn’t mind’’ being asked to perform a five-minute rupture on the at times dystopic Fordian roadways that are more often than not at a standstill anyway. The work reenacts a significant experience of the city many would recognize; delivery trailers reversing to jam the traffic on a Mexico City freeway exit are not, in fact, uncommon. Nor is its location arbitrary. The work is observed from a footbridge loaded with its own history of violence and protest, while toward the rear stands Gonzalo Fonseca’s 1968 Torre de los vientos (Tower of the winds), a sculpture that forms part of the Ruta de la Amistad (Route of friendship), a seventeen-kilometer-long sculpture park designed to be viewed by drivers on their way to the Olympic stadiums for the 1968 games.

Courtesy Archivo Historico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City

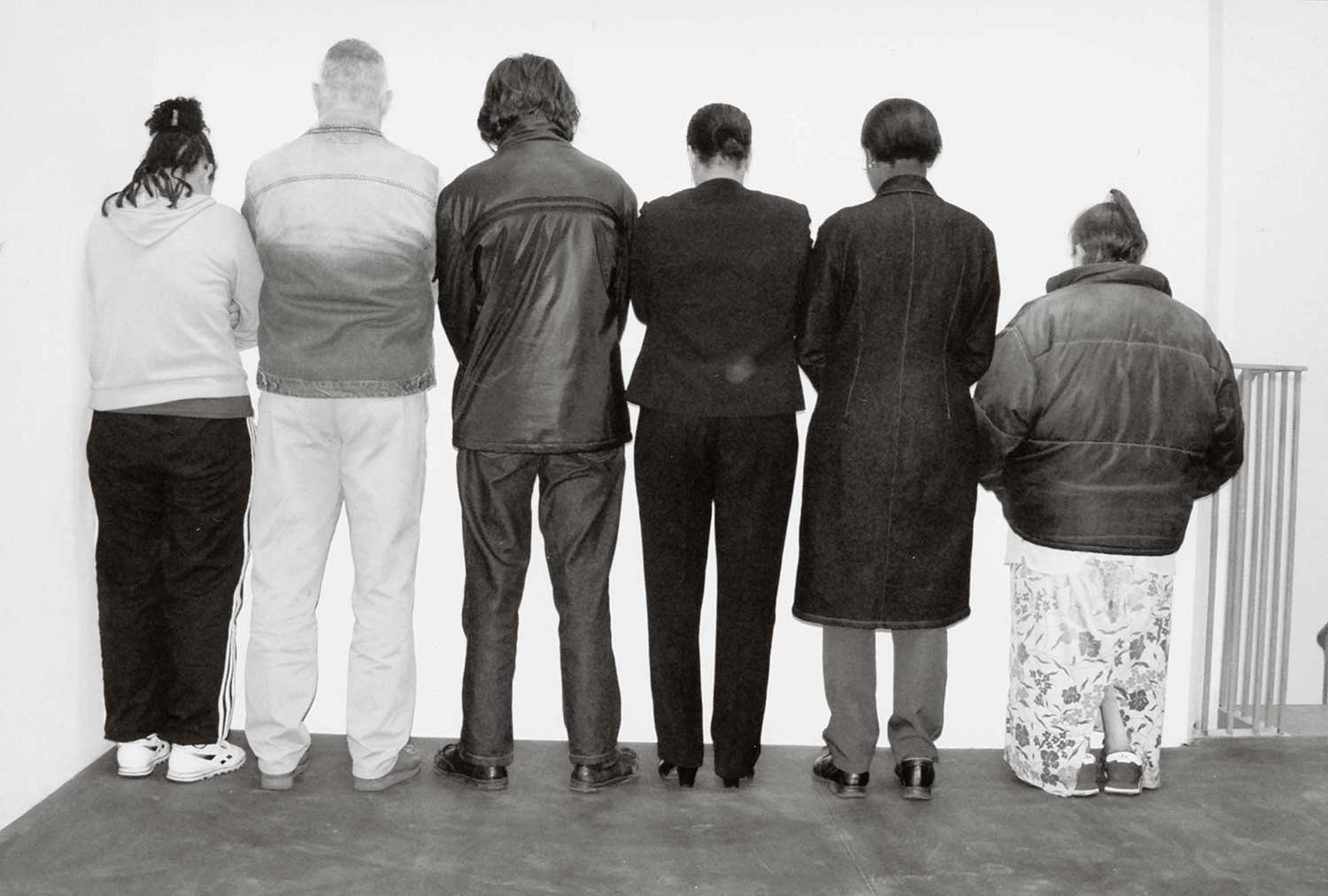

More broadly, Sierra’s actions emphasized capitalist imbalances and dehumanizations as part of a broader question of institutional power versus the individual. In a series of works realized both in Mexico and elsewhere, Sierra imposed his art directly on people’s bodies, replicating the conditions of exploitation for remuneration that are often found in Latin America. The lines of bodies that appear in his photographic documents—whether of addicts being paid the price of a heroin fix to be tattooed or of the unemployed to simply stand against a wall—echo photographs of the student oppression by police during the protests at the time of the 1968 Olympics. In particular, one piece of reportage stands out as an antecedent: Manuel Gutiérrez Paredes’s photograph of the police searching detained protesters. Cemented in the Mexican cultural imagination, this lineup of subjugated students arrested at the Tlatelolco demonstrations, where forty-four people were killed, lingers more than the constructed media images that the games were meant to project. As the president of the Organizing Committee of the games stated: “Of least importance was the Olympic competition; the records fade away, but the image of a country does not.’’ Undoubtedly, such brutal authoritarianism would be the lasting image, even if it was a distinctly modern one, compared with the rural depictions that persisted prior to the 1960s. It is not merely the physical but also the psychic resonance that is embedded in reportage of events like this, or of the subsequent traumas, captured by photographers such as Enrique Metinides, of violent robberies, plane crashes, and disasters. While veracious in many respects, these pictures amplified imagery of violence and “low’’ culture over other more positive aspects of life in Mexico City.

Sierra’s and Alÿs’s photographic works are often deliberate snapshots not intended to be part of the photographic canon per se, but rather a use of the camera as an apparatus of vérité and documentation. Sierra’s images, perhaps more than others, are consciously engaged in creating a particular idiom. The choice of black and white at a time when color film was already the norm lent a deliberately staged air to the records of his actions. Both Sierra’s and Alÿs’s form of photography sits between journalism, documentary, and the street photography of Weegee and his ilk. Certainly it is informed by these traditions in its framing and intention, just as it is informed by post-Minimalist and Conceptual art imported from the United States and Europe.

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich

In 2002, Melanie Smith, a British-born artist (who contributed to the 1990s art scene in Mexico City with the weekly Mel’s Café she ran in her studio then), created Spiral City, a project including a movie and still photography of Mexico City that pay homage to Spiral Jetty (1970), Robert Smithson’s landmark earthwork tucked behind a remote promontory of Utah’s Great Salt Lake and his film of the same name. Smithson’s film is not only an image of Spiral Jetty and its landscape; it also explores cultural ideas and phenomena that are just as influential in constructing the mythology of a place, such as science fiction and natural-history museums. These intercut references add a modern mythical dimension to his documentation. Smith applied Smithson’s methodology to Mexico City, itself constructed on a drying lake bed. In Spiral City, the seemingly boundless grid of Mexico City’s housing, all low-rise and barren, whether in low-income or middle-class neighborhoods, has the same sense of accretion as Smith’s inspiration. Her film moves at a biological rather than geological speed as it pans over mainly informal and unplanned dwellings. Seen in this way, the city resembles Mike Davis’s description of it, in his book Planet of Slums (2005): “The giant amoeba of Mexico City, already having consumed Toluca, is extending pseudopods that will eventually incorporate much of central Mexico, including the cities of Cuernavaca, Puebla, Cuautla, Pachuca, and Queretaro, into a single megalopolis.’’

This is not to suggest that these practices were the only approaches of relevance in the 1990s and into the early 2000s. Gabriel Orozco was producing sculptural interventions in dilapidated interiors, vacated lots, and other liminal urban sites in both Mexico and New York, where he was simultaneously based. Many of these assemblages of discarded materials appear animate, suggestive of mythical figures as much as of playful forms, drawing on two distinct histories of modern and premodern to forge his own hybrid aesthetics. Silvia Gruner was using her own body as a tool to explore relations with traditions and identities, which also reflect the dualistic time frame in which Mexico seemed to exist.

Courtesy Estate of Candy Jernigan and Greene Naftali, New York

Mexico City has always been full of extreme contrasts. Another facet, one that few artists have engaged, is that of the enclosures of the wealthy industrial classes, the thirty-eight families who control the majority of economic and political power in the country. Daniela Rossell’s portraits of society women in their homes, grouped together under the series Ricas y famosas (Rich and famous, 1994–2001) and Third World Blondes (2000–2002), are the exception, although they also play with certain stereotypes. How these images were produced and circulated are as significant as what they portray, revealing the codes of viewing embedded in both local and international contexts even more acutely than artists who work in Mexico City’s public spaces. Rossell’s portraits are remarkable on many levels. Among the first thing one notices about their main subjects is their propensity to be blond, a social marker among Mexican wealthy classes that differentiates them from their housekeepers and maids, many of whom appear in the photographs in subservience to their employers. The homes of these women have been referred to as gilded cages, and the overadornment of their interiors is akin to those of the bodies that inhabit them, often with fantastical implications—for instance, one woman is seen dressed as a mermaid with Medusa-like hair, with the bed as her sea, and a Native American doll lying beside her.

Courtesy Estate of Candy Jernigan and Greene Naftali, New York

Rossell’s work was produced in full cooperation with her subjects; Rossell, who is from the same class herself, was able to gain access to these extravagant homes through family and social ties. We can see these photographs as representations of people as they choose to present themselves. In this light, perhaps it is too easy to judge the excessive taste and apply the same criteria to the person within the image. Somewhat inevitably, once unveiled to the world at large, these isolated creatures and their exotic artificial universes were critically addressed in the media and by art-world cognoscenti for the brash way in which they displayed and performed wealth. Once it became clear that they had become the subject of ridicule, many of those pictured withdrew their consent. Given the nature of family businesses and the nature of business itself in Mexico, often intertwining legitimate and not-so legitimate practices, Rossell found it impossible to continue with the project, and found herself under genuine threat.

The images in Ricas y famosas are, in fact, neither celebratory nor parodic, but rather a means of addressing attitudes toward women, particularly in the media. It should not be overlooked that the series’ title is itself taken from a long-running telenovela and suggestive of the vacuous stereotypes it portrays. Arguably, Rossell’s lens reveals not just the absurdities of wealth but also the public mores and judgments of the upper class—demonstrating a self-awareness that is noticeably lacking in the art of her European colleagues working in Mexico during the same era, who often placed acts within a deprived social sphere without truly being part of it.

Read more from Aperture issue 236, “Mexico City,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

(Visita gatopardo.com para leer este artículo en español.)