Can this Young Photographer Dissolve the Drama of Gender?

Akin to Caravaggio, the humanist Baroque painter of the double-edged scene, Michael Bailey-Gates serves ambiguity atop ambiguity to get at the underlying truths of living in a pre-apocalyptic world. This is accomplished most directly by Bailey-Gates’s capacious understanding of the work of the close-up and a refracted, almost restrained use of color. The close-up has become visual lingua franca in the age of the selfie. It was Nan Goldin and Cindy Sherman in the 1970s and ’80s who borrowed the close-up from cinema to speak truth to power in a divided Thatcher-era, Reaganomics world. Whereas Goldin’s close-ups are of half bodies, writhing together so that the tail-end of one sits on the mouth of another in a Mobius strip of nonlinear, undefinable narrative arch, Bailey-Gates’s close-up always includes the eyes of the subject(s) and often the knees. This redoubled fixation on the computational apertures onto human experience and the joints which propel action through the world is startling.

Through Goldin and Sherman, we learned that the close-up lends a humanist lens with which to view an event, but occludes knowledge of everything else in the frame. The close-up provides deep information about a single situation, but renders everything else in fractals. The close-up under their respective kneading became symptomatic of Western culture’s slippage into the postmodern. Bailey-Gates flips this existential form born of cultural angst on its ass—turning transgression into emo transliteration for this new post-postmodern milieu. The close-up in the social media era is now referential of the early-modern painted allegories that were neither sacred texts nor portraiture, but instead a third genre, one conscious of the subject’s transition from human to critical referent. Whether in studio shots, movement studies, genre scenes of bodies in nature, or staged images lit by candles and studio lights, Bailey-Gates frames a close-up that is neither the caress of a third lover nor the blatant impatient stare of the voyeur, but rather the wink of collusion by a knowing accomplice.

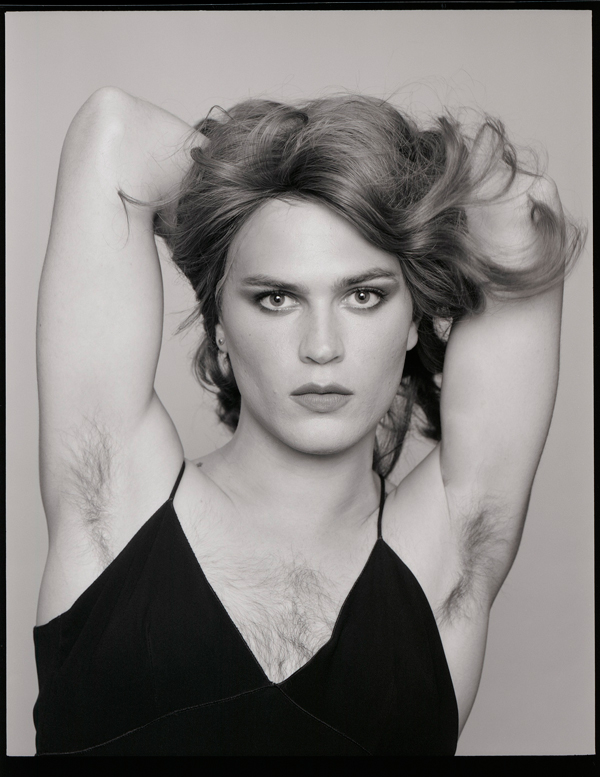

The existential drama of gender and being dissolves before Bailey-Gates lens. Bailey-Gates’s photographs don’t so much interrogate gender as bypass it. With these photos, I’m not just unconcerned with reading the gender of the bodies before me, it’s also futile. The photographic close-up is now an opportunity to collaborate, to collude, to build the little life of a narrative where there was none. The subject becomes less important for who and what they are and dearer to us because of the network of intimacies and experiences they represent.

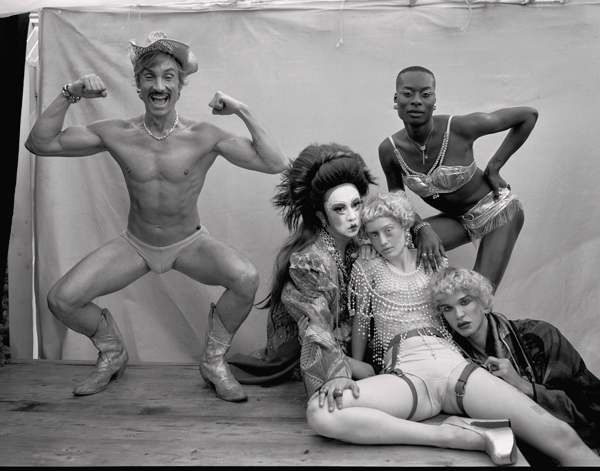

This post-postmodern matrix of ever-expanding intimacies and experiences is what links and distinguishes Bailey-Gates’s attentions to and from the lush austerity of George Dureau or the slick provocations of Robert Mapplethorpe. There is something quintessentially New York about Mapplethorpe; something indelibly Cajun about the New Orleans born-bred-and-died Dureau. There are no tell-tale signs of where Bailey-Gates’s images are conjured from, only a decisive when: the now of our imaginings. I can’t help but see this distinction as one of color, that shifting and shifty attenuator of form and light. Both Dureau and Mapplethorpe are hip to the close-up game: using intimate acts as a way to turn the circus tent and the bathhouse into a studio. Both employ light as a way of rendering the nude or leather-clad body as sculpture, with all the tricks and displacements neoclassicism provides in a postcolonial world.

Yet both photographers were decidedly male and decidedly gay, with a decidedly uninterrogated male gaze. Both men often photographed their subjects against light backgrounds so the formal taxonomy of limb-to-limb ratios could be enacted. This doesn’t mean their work sucks or is unimportant, it just means the images have no desire to appeal equally to canonical and individual standards of beauty. Their work is not interested in providing a modulated, inclusive vision of truth. Bailey-Gates does not fall into this myopia. Entanglements of power and dependency—electric, historic, proximate—form the compositional landscapes of Bailey-Gates’s formal intersubjectivity. Whether shooting from above and looking down on subject(s) giggling on a bed, or from below with subject(s) carousing above, or shooting bang dead-on, the camera’s aperture filling with the light from subject(s) eyes, Bailey-Gates gives us an expansive gaze—often photographing against dark or riotous backgrounds so that the composition is sonic rather than lucrative and tight.

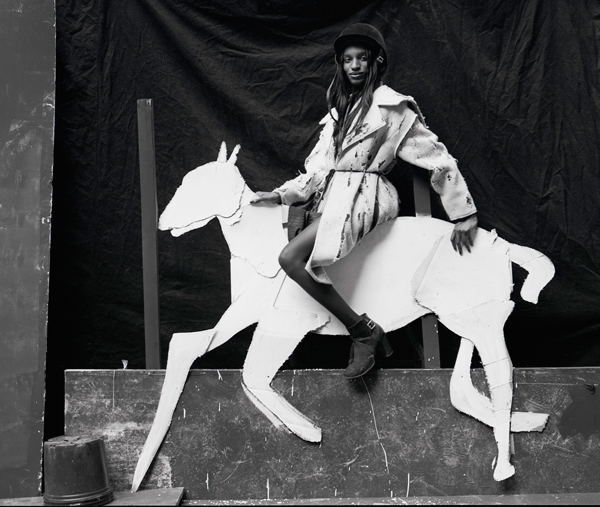

And while Mapplethorpe and Bailey-Gates are both referential (Mapplethorpe to Thomas Eakins; Bailey-Gates to Marc Jacobs looking at Mapplethorpe looking at Thomas Eakins), only Bailey-Gates is able to mobilize color as a way of referencing past and coeval commercial and editorial modes of looking. These images capture the criticality of pop culture citation and the body’s relation to luxe fashion as both an experience of material and an imagined fluidity of pigment. It seems to my eye that color and citation function in a Bailey-Gates photograph as analogues to critical relations to gender: something we step in and out of, something we try on, wear, perform, then discard if it prevents the kind of encounter we crave.

It is the worst-kept secret in culture that sculpture, fashion, and the photograph are the same boi in a new wig. The triplets arise from the same impulse to capture and sustain the body mid–free fall as it navigates Time. These three visual modes provide a body or a subject added dimensionality as it moves. Judith Butler reminds us that gender is constituted in these visual and material mediations through time and space. Neither fixed nor periodically stable, gender is for Butler a tenuous “locus of agency” that provide an illusion of coherence via a stylized sense of repetitive acts. To put it more succinctly, gender is its own dimension through which the human subject as form walks in and out of with every word, act, and thought.

Back to color. For Bailey-Gates, color is applied across these photographs conscientiously in order to suture the photographic event in Time. The black-and-white images do not read as matte or neutral, but as substantial poetic forms in which our expectations are meant to be affirmed then subverted. The photographs with warm palettes leave the realm of deep time and position us in the immediate present where a decision is about to be made and we are about to bear witness to its unfolding. Color implicates the viewer in the mutual creation of a communal gaze that is joined and spread digitally. I cannot tell where the spiraling web of fashion affecting Instagram affecting ourselves and our posts to Instagram affecting what’s on trend begins. What Michael Bailey-Gates’s images convey, however, is the enduring importance of this ever-widening gyre to include more narratives and more bodies in the “visual tectonics” of culture. But where will it lead?

In a future time, say two, three generations from now, cyborgs will recover the photographs of Michael Bailey-Gates as the first flourishing of themselves. Cyborgs, you understand, don’t have sex. They don’t need to, as the network they are all tuned into for their being is a constant and consistent matrix of connection and interrelationality. They also don’t do clothes. But the cyborg body is a pleasuredome of expanse served in circuited refractions of genderplay and agency, and the digital photograph serves this up with all the jolt of mainlining caffeine. They keep their humanoid shape as homage to us, their great grandparents.

All photographs courtesy the artist

Bailey-Gates knows this. Bailey-Gates’s surname will flicker in neon Helvetica across the cyborg chest—between the on and reset switches of memory. The transmodalities of the cyborgian mind-space continuum allow them to conjure the pages of MATTE from thin air in order to learn when the photograph in the digital age stopped serving facets of reality and began inventing futurities. Bailey-Gates is going to be a band name of epic post-hip-hop-punk potentiality in this future age. Draft an email to your children’s children. Tell them you peeked this visual revolution first.

This essay originally appeared in MATTE magazine, issue 53, 2019, and is republished courtesy the author.