For a New World to Come

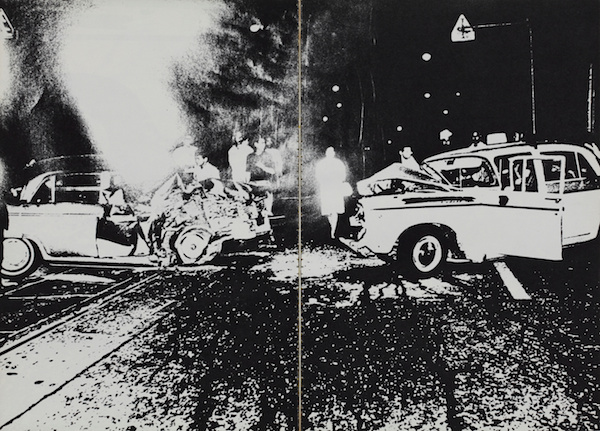

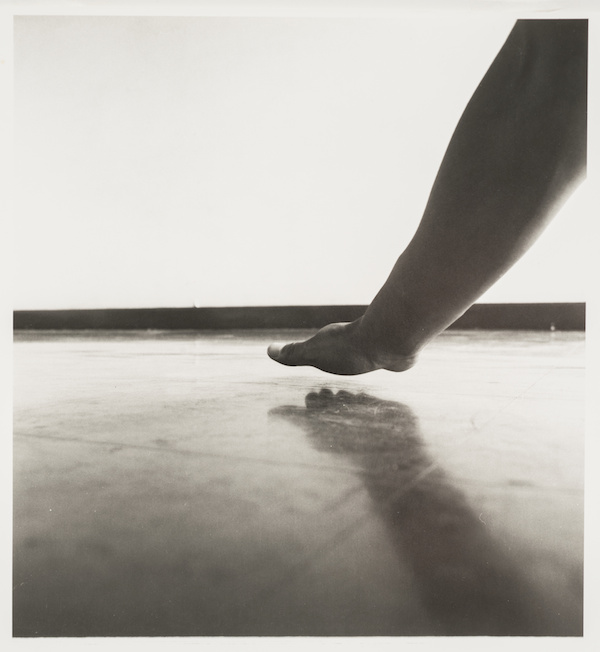

Daido Moriyama, from Asahi Camera, 1969 © Daido Moriyama and courtesy Tokyo Polytechnic University, Shadai Gallery and Taka Ishii Gallery

Aficionados of photography from Japan will find surprises—and their assumptions challenged—among roughly 250 works included in the fascinating exhibition For A New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Photography, 1968-1979. The exhibition explores avant-garde artistic output during a decade in Japan marked by widespread student protests, economic flux, and transformative urban growth. While the show includes legends like the Provoke-era master Daido Moriyama, the famously provocative Nobuyoshi Araki, and Shomei Tomatsu, who cast a critical eye on the American occupation of Okinawa, many of the twenty-nine artists featured in this show have never been exhibited before in the United States. By delving into the nexus of photography and conceptual art, the exhibition presents a trove of unseen works in the forms of gelatin-silver prints, graphically seductive books and magazines, homespun Xerox projects, videos, and other pieces that bridge photography, painting, and sculpture. The exhibition, which is accompanied by a catalog full of scholarly essays, is revelatory and opens up a rich history for American audiences.

Aperture magazine editor, Michael Famighetti, recently spoke with curator Yasufumi Nakamori about his show, which opened at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, before traveling to New York, where it was split between Japan Society and the Grey Art Gallery, New York University. Nakamori also contributed a related essay to Aperture magazine’s “Tokyo” issue.

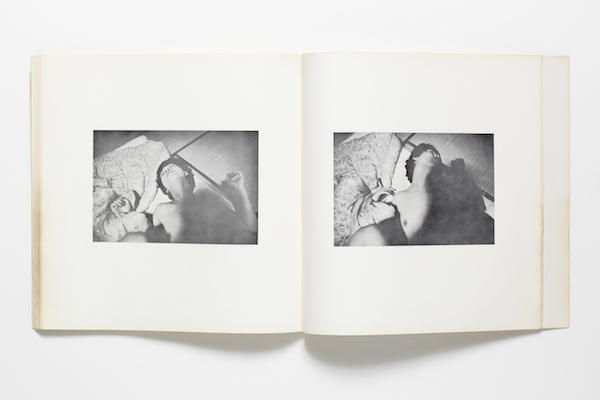

Araki Nobuyoshi, Sentimental Journey, 1971 © Nobuyoshi Araki

Michael Famighetti: This exhibition is, in part, a response to curator John Szarkowski’s 1974 MoMA exhibition New Japanese Photography, which introduced an American audience to post-War figures, such as Shomei Tomatsu and Daido Moriyama. For a New World to Come includes some of these same names but introduces many other practitioners. What was the starting point for your research into experimental work of this period?

Yasufumi Nakamori: The exhibition research continued for two years. My research partner, Yuri Mitsuda, a Tokyo-based art critic, and I first looked at several dozen photographers and artists (painters and sculptors) who were making experimental work with the camera in the 1970s, and at several exhibitions that took place mostly in Japan, as well as in the U.S. and Europe.

We meant “experimental” to mean a wide range of experiments, both personal and collective, including emerging conceptual and post-minimal practices. This was a decade when Japanese society had undergone radical transformations in politics, economy, and cultural production. We were primarily interested in how artists and photographers, freed in the late 1960s from the rigorous orthodoxy imposed by the academy, responded artistically to this cultural shift. Artists crossed the boundaries of fine arts and photography; the two mediums had their own distinct histories until then. We were interested in finding out what had not been shown (as an exhibition) or discussed (within scholarship). In our exhibition and publication, we have shown successfully that, contrary to the general perception, in the 1970s, numerous Japanese artists and photographers were engaged in experimental practices with the camera. They were aware of international trends and laid a foundation for the field of contemporary art, where photography plays a critical role.

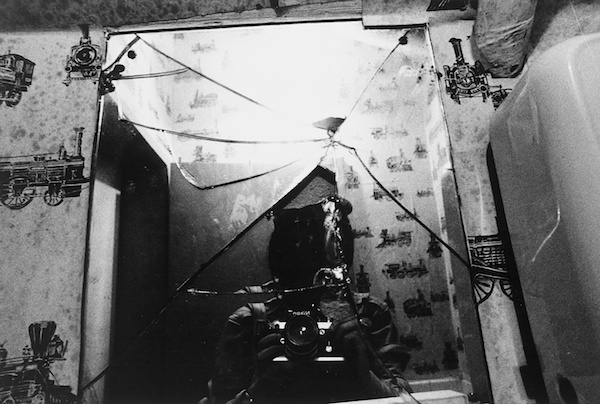

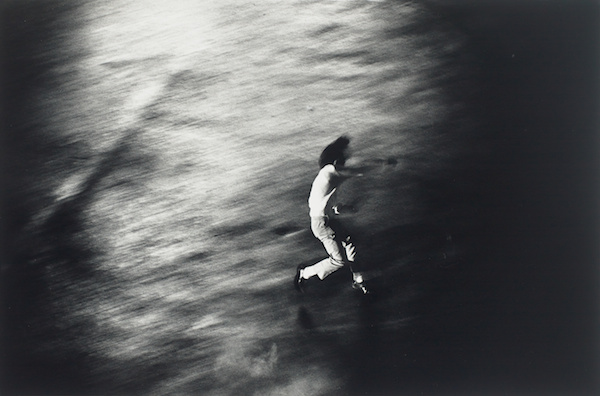

Takuma Nakahira, Untitled, 1968–1973, printed 2014 © Takuma Nakahira

MF: The exhibition’s title is a play on Takuma Nakahira’s book For a Language to Come (1970). How does Nakahira serve as a touchstone for the show?

YN: His publication, filled with his Provoke-era photographs of the city, characterized as are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus), is certainly the beginning of the exhibition. However, I was more interested in his shift that took place in the early 1970s, from his signature black-and-white photographs to his large-scale installation (twenty feet across) of forty-eight color photographs, known as Overflow (1974). Earlier, Nakahira insisted that written language was no longer sufficient to portray the complexities and nuances of the time, and proposed for photography to fill the older medium’s deficiency, as the new Japanese culture known as eizo gengo (image language) surfaced.

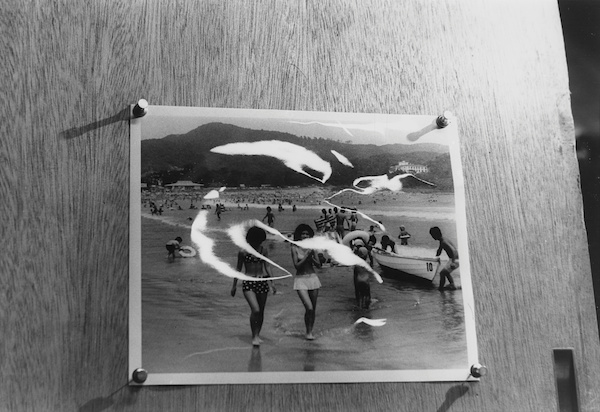

Jiro Takamatsu, Photograph of a Photograph (No. D-2401), 1972 © The Estate of Jiro Takamatsu and courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates

With his anthology of essays titled “Why an Illustrated Botanical Dictionary?” (1973), Nakahira defied his then-recent past and advocated for color photography to accurately reflect Japanese society in the 1970s. In the installation at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, I traced this shift in Nakahira’s photographic practice. Additionally, Nakahira was important for the exhibition because he connected the worlds of photography and contemporary art in 1970s Japan. For example, his photograph of a desolate part of the Tokyo Bay was used on the cover of the catalogue of the 10th Tokyo Biennale, titled Between Man and Matter (1970), an important exhibition that introduced conceptualism to Japanese audiences. In my show, I featured artists Jiro Takamatsu, Koji Enokura, Hitoshi Nomura, and Tatsuo Kawaguchi, who were shown in Between Man and Matter.

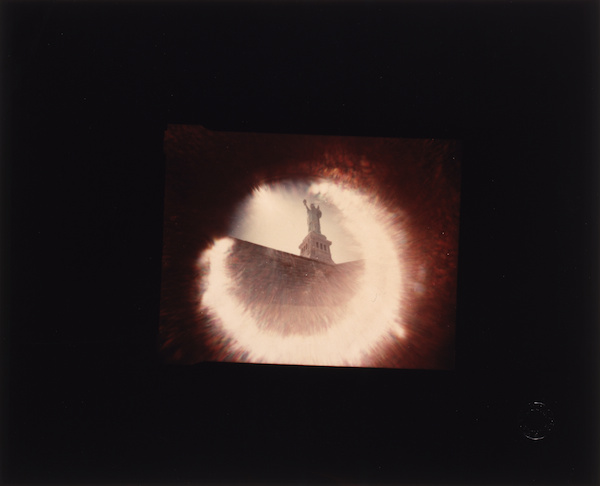

Nobuo Yamanaka, Manhattan in Pinhole 1, 1980 © Nobuo Yamanaka

MF: Such names will likely be new to visitors of the show in the States, but how well known are these artists in Japan?

YN: Artists such as Kazuyo Kinoshita, Masafumi Maita, Nobuo Yamanaka, and photographers like Kiyoshi Suzuki, and Kenshichi Heshiki are known among specific (and relatively small) audiences in Japan.

Yuri Mitsuda and I both grew up in the 1970s in the Osaka/Kobe area and we were keen on moving away from Tokyo-centric art and photography. This is what has been shown in a number of U.S. exhibitions of post-War Japanese art, such as New Japanese Photography (MoMA, 1974), Japan: A Self-Portrait (ICP, 1979), and Tokyo: A New Avant-Garde, 1955–1970 (MoMA, 2013). However, exhibitions like Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky (Guggenheim Soho, 1994), Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s to 1980s (QMA, 1999), and Gutai: A Splendid Playground (Guggenheim, 2013) certainly indicated a direction for an interdisciplinary methodology for my current exhibition.

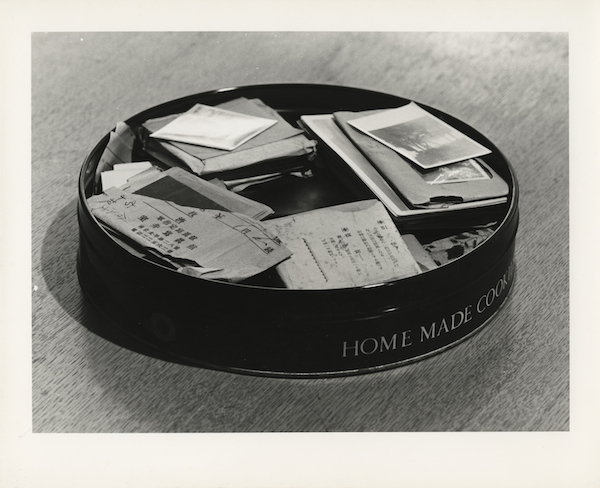

Kiyoji Otsuji, Past of One Tin Can, from the series Otsuji Experimental Laboratory, 1977 © Seiko Otsuji

MF: The Provoke figures were influenced by French thought, by authors such as Alain Robbe-Grillet, to name one example. A poet was among the founders of Provoke. Nakahira saw photography as exceeding written language. What was the relationship between the literary and photography worlds in Tokyo at this time?

YN: An excellent question. Nakahira studied Spanish, French philosophy, and literature. Takahiko Okada, one of the Provoke collective members (the only non-photographer member), edited, along with the Surrealist and photographer Kiyoji Otsuji, the December 1968 issue of Bijutsu techo (Artists’ Notebook) that was entirely devoted to the history of photography. Another Provoke collective member Koji Taki, who was familiar with, among many other things, the literature by Walter Benjamin, soon began writing criticism on art, photography, culture, and architecture. Provoke was certainly marketed in both photography and literary circles. Nakahira can be situated in a group of writers and artists who advocated for the emerging field of eizo gengo (image language) in the 1970s. The terminology is arguably derived from the French film critic André Bazin’s book What Is Cinema?, which was released in Japanese translation in 1970. Nakahira’s familiarity with the literature and films by French artists, such as Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962) were relevant to his photographic projects, like his 1971 Circulation: Date, Place, and Events, created at the Paris Biennale. Nakahira’s color photo installation Overflow (1974) can be interpreted his dreamlike non-narrative of a city wanderer, a psycho-geographical photographic experiment, perhaps informed by Guy Debord.

Shomei Tomatsu, Protest 1, from the series Oh! Shinjuku, 1969, printed 1980 © Shomei Tomatsu and INTERFACE

MF: A tension between Tomatsu and his vision of photography, which was experimental in its own right, and the Provoke photographers, plays out in the exhibition. That said, both Tomatsu and the Provoke figures were pushing the language of photography. How much of this was an aesthetic battle vs. a regional battle (Osaka vs. Tokyo)? Or a question of inclusivity vs. exclusivity?

YN: Tomatsu was slightly older than both the Provoke photographers and those associated with konpora (a shorthand in Japanese for “contemporary photography”), who were known for their deskilled snapshots of the everyday. Tomatsu thought both of these camps were nonsense, though he maintained a certain relationship with the Provoke photographers. Tomatsu himself also took some out-of-focus photographs (a stylistic hallmark of the Provoke group), like those he shot in Okinawa. Self-taught and self-established, Tomatsu was never interested in being a passive member of any collective, after his participation in the photography collective VIVO, in the 1960s. He started a publishing house (Shaken), a magazine (Ken), and an alternative photography school (Photography Workshop). His vision for photography—and Japan—went beyond the Tokyo-centric, New Left elite discourse. He traveled to Okinawa before the island was repatriated to Japan in 1972. In the early ’70s, he began looking at even Southeast Asia. His dialogue extended outside the narrow field of photography and the city of Tokyo.

Shigeo Gocho, from the series Familiar Street Scenes, 1978–1980 © Hiroichi Gocho

MF: You mentioned konpora, the term used to describe the snapshot aesthetic seen in the work of photographers such as Shigeo Gocho. Your exhibition catalog text points to Nathan Lyons’s 1966 George Eastman House exhibition Contemporary Photographers: Toward a Social Landscape as a influence on this style of photography in Japan. Presumably, the catalog for that show circulated widely in photo-circles in Japan at that time?

YN: Yes. My understanding is that the American exhibition catalog and Otsuji’s writing about the exhibition in a 1968 Mainichi Camera issue circulated in Japan and at major photography schools, like the Tokyo College of Photography.

MF: The exhibition highlights the role of the photographer-run, independent gallery and photographer-run magazines. Did photographers need to create, in effect, their own institutions?

YN: I believe they did. Given that there was no commercial market, photographers needed to create their own opportunities to show (and sell) beyond commercial photography magazines, like Mainichi Camera and Asahi Camera. The short-lived Workshop Photo School (established by Tomatsu but which also included Araki, Noriaki Yokosuka, Masahisa Fukase, Moriyama, and Eikoh Hosoe) was extraordinary. In addition to teaching photography, these teachers published quarterly journals and attempted to create a photography market. In 1976, for example, they set up an exhibition where they and their colleagues sold prints. From the Workshop Photo School, numerous independent photography spaces, such as Image Shop CAMP, Prism, and Put emerged.

MF: This is a big, ambitious show, featuring twenty-nine artists. What challenges did you encounter?

YN: As I mentioned, it took me and Yuri Mitsuda, my research partner, approximately two years to do the research. I met all of the artists or representatives (if the artists were deceased or ill), except for two. As we finalized the selection of works, it was important to figure out what the decade of the 1970s and the idea of “experimental” meant to these artists. A major challenge was that I needed to create the ambitious exhibition and publication (of eighteen essays by thirteen authors) within a reasonable budget, which was not huge.

MF: The idea of what’s “experimental” means many things in this show.

YN: Most of the artists and photographers in the exhibition sought out to find new ways of seeing with the camera, freed from traditional ways of seeing taught at the academy. Such experiments could range from conceptual, to intermedia/interdisciplinary, and to performative. Introduction of seriality to express the element of time was also seen often. Each experiment observed in the show is personal, yet international. International contemporaneity observed through various experimental practices is the core of the exhibition.

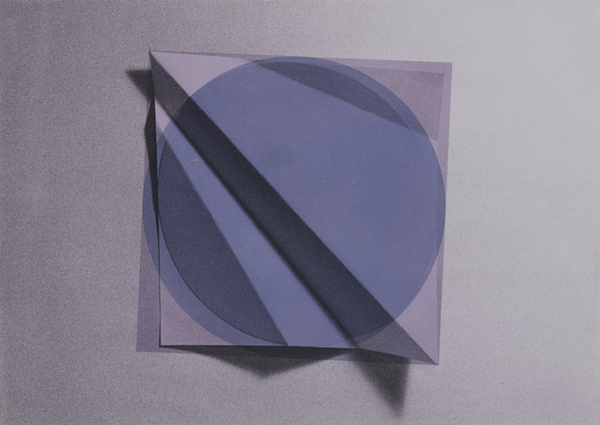

Kazuyo Kinoshita, 79-38-A, 1979 © Kazuyo Kinoshita

MF: Were any of the artists new discoveries for you? What did you learn as a scholar/ curator that was unexpected?

YN: Personally the artists Nobuo Yamanaka and Kazuyo Kinoshita were new discoveries to me. Both Mitsuda Yuri and I felt that we needed to bring up in the exhibition most experimental aspects of each artist/photographer’s practice. The sculpture/photography installation by Keiji Uematsu, who installed his site-specific sculpture Cutting both in Houston and New York, brought an experiment to me as a curator of photography. Reconstructing the late Yamanaka’s Fixed River (1972) based on research that we conducted was both a challenge and a learning experience.

Koji Enokura, P.W. No. 51, Symptom—Floor, Hand, 1974 © Michiyo Enokura and Photo: Paul Hester, Hester + Hardaway Photography

MF: The exhibition is strictly bracketed by the years 1968–1979. Did this spirit of experimentation cease in the 1980s, as Japan surged economically?

YN: I tend to think that the experimental spirit waned as many of the photographers and artists began to have access to capital, art commissions, and other opportunities to sell and do more commercial work. The dominance of color photography in the 1980s also changed the conceptual/experimental practice found previously.

Toshio Matsumoto, For the Damaged Right Eye, 1968. Triple 16mm film (transferred to DVD), color, 12 min. 9 sec. Matsumoto Toshio © Toshio Matsumoto, Photo: PJMIA

MF: Now that you’ve unpacked this incredibly rich decade of photography, where will you turn your attention next as a curator? Do you see another lacuna in the narrative of photography from Japan that should be brought to an international audience?

YN: A serious investigation of the aforementioned Photo School Workshop as an artistic movement, in relation to the collapse of modern photography observed in the mid-1970s, should be done.

For A New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Photography, 1968-1979 is on view at Japan Society in New York through January 10, 2016.