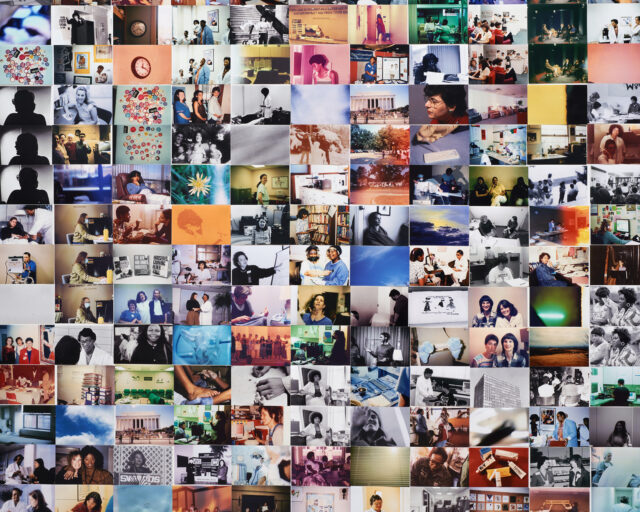

Notes on a Scandal

After weathering the media firestorm surrounding a series of provocative self-portraits, Lebanese photographer Rasha Kahil turns comments from online trolls into a powerful exhibition.

Rasha Kahil, Hackney Wick, E9, London, from the series In Your Home, 2011

Courtesy the artist

For her photographic series In Your Home (2011), Rasha Kahil a London-based, Lebanese artist, photographer, and art director, depicted herself in seminude poses in people’s homes in London, Berlin, and Beirut. Kahil presented the work in Beirut and Istanbul and self-published the series in London in 2011. Confined at first to art world circles, In Your Home later caught the attention of local Lebanese news outlets when, in 2013, Al-Jadeed TV produced a report on Kahil. Her images became an instant sensation and the coverage subsequently catapulted Kahil into the ruthless public domain of social media. Anatomy of a Scandal, Kahil’s new work, is a multimedia installation that delves into her response.

Rasha Kahil, Kastanienallee, Mitte, Berlin, from the series In Your Home, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Rayya Badran: In Your Home, made between 2008 and 2011, is a series that challenges issues of intimacy and private space. Yet, the later occultation—censorship—of the erotic parts of your body was itself a violation, not merely bestowed upon your body, but also a violation of what your work had intended to do in the first place. Your reprisal of these reworked, retouched works sheds light on the ease with which the Internet can appropriate and deconstruct images at will. Instead of actively challenging them, you chose to surrender, if one can say that, to that noise. I wonder about the subversive potential in such a decision. Radio silence as a position of power.

Rasha Kahil: As the “scandal” happened online, I did choose to stay silent. It wasn’t so much an act of resistance at first, but instead a realization that the power of the Internet, and the free-flow of voices who either choose to condemn or champion, is a torrential force that can only be observed in real time, not one I can actively engage in. Observation was my only recourse; documentation my only tool.

Being at the center of a such a vigorous media storm and witnessing the flurry of comments aimed at my body, my work, my being, was at first extremely harrowing, especially because there were many attempts to contact me directly, rather than just “reading” my person being dissected online. I was hounded by TV talk show hosts who asked me to participate in live TV panels and “defend” my work, give my side of the story. Of course, I was never going to do that, and I chose to remain silent, as not only is attempting to engage with the strength of the online voices a futile exercise, but, of course, agreeing to add my own voice to the discourse would only mean that I was giving validity to the wider discussion.

Therefore, proactive silence was my only course of action, and my strongest tool. I actually found the deconstructed images of my original In Your Home series churned out by the media outlets online—with their liberal use of pixels, black bars, and Photoshop blurs and splodges—quite fascinating. I am not sure “surrender” is the right word, as my silence was my own form of attack: it never crossed my mind to issue an apology to the singular “mass,” as seems so customary an outcome in these types of online scandals.

Rasha Kahil, Caledonian-Road, N7, London, from the series In Your Home, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Badran: Before you moved onto the dissection of people’s responses to your work, and aside from the very polarizing, yet somewhat predictable opinions out there, was there a response among those that were sent or posted that particularly marked you or made you pause? And could you explain why?

Kahil: Yes, it is a comment left on a blog post that I actually used as a stand-alone vinyl piece in the exhibition:

unfortunately, none of Rasha’s so-called artistic pictures meet the conditions needed for a piece of work to be considered as art:

art: something that is created with imagination and skill and that is beautiful or that expresses important ideas or feelings/works created by artists: paintings, sculptures, etc., that are created to be beautiful or to express important ideas or feelings. [from the Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary]

Obviously, these pictures only display vulgarity, fruitlessness and lack of creativity, which are the complete opposites of the two definitions of art mentioned above (that’s just to say a little about her pictures). Plus, they serve no important or noble purpose and are thus pure garbage porn.

Last point I want to make is, looking at this girl’s pictures, all I could possibly see is a stupid, wrathful, disguised feminist rebelling at the very end of the continuum and more importantly, a promising Arab porn star … wow! Very honorable and educational material for generations to come …

It is the violence of the tone in the comment that really struck me. Most of the comments left online were throwaway remarks, using my body as a springboard for “locker-room banter” (as Trump would say, defending this type of discourse). But this particular comment is considered. It reads like a mini-essay, with a moderate intro, a heated argument, and a progressively more vociferous closing statement. There seems to be deep-rooted revulsion towards my work and persona, manifest in an attack not only on my practice, but also my intellect, my body, my gender, and my intentions all at once. It unsettled me deeply, not because it zoomed in on me personally, but because I feel it to be a violent attack on women in general and vocal, outspoken women in particular.

Rasha Kahil, Anatomy of a Scandal, installation at Art First Projects, London, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Badran: Did you place any criteria for selecting the posted comments? What was the narrative you sought to bring to the surface from the flurry of online opinions?

Kahil: I incorporated all the emails I received as part of the framed wall installation. Since they are private, one-to-one emails, the names are cut out of the paper printout to protect the identity of the sender. As for the Facebook comments I used in the video, it was a question of using a diverse selection, so as to give the most accurate representation of the sheer volume, as well as the overarching themes, of the discussion that was happening. Some of the comments I narrate in my own voice are also arguments that happened between commenters amongst themselves, and I embody both polar positions through my voice.

Rather than a narrative, the installation is a documentation of the happening itself. I am the author of the installation and my arrangement of the different “scandal” elements constitutes a form of storytelling. In a sense, it’s a translation of a virtual experience into a physical experience. The elements are all there, untouched—the comments, the emails, the censored images—but my architectural layout of the components is my way of re-appropriating this experience, neutralizing it, and displaying back to the original creators. The work is the result of my sustained forensic collecting of these artifacts during my “radio silence” and their subsequent transformation into physical objects.

Rasha Kahil, Anatomy of a Scandal, installation at Art First Projects, London, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Badran: You display comments from those in your defense and from those who attacked your photographs. Why was it important for you to re-enact the social media comments yourself, with your own voice?

Kahil: I wanted to start a dialogue about what it is to be an artist and a woman in a patriarchal society. So, the use of my voice to narrate the different comments, both in defense and in condemnation of my work, is my way of owning the orchestra of voices, in contrast to having remained silent while it was underway. Personally collecting, transcribing, and retelling the running commentary in my own voice seems to have disarmed the violence inherent to the commentary, and revealed its farcical undertone. There was a lot of giggling and laughter at the opening of Anatomy of a Scandal in London last year, which was something I had sensed would happen and very much welcomed. Is laughter the best medicine? Not always, but in the case of this scandal, turning it from a violating experience into a tragicomedy laced with absurdity was the best way to move beyond the initial violent assault.

Rasha Kahil, Whiston Road, E2, London, from the series In Your Home, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Badran: Nina Power, a British writer, teacher, and critic, recently wrote as a preface for an essay entitled “How do you visualise a woman in the 21st century?”:

The battle to visualise ‘a woman’ or to give shape to the category of women in the 21st century will take place mostly virtually and linguistically but the consequences will be material, as they always are. We must go through the violence of the image in order to arrive at something else—a non-violent, non-image that can still, somehow, be understood.

Do you align yourself with this notion that one must go through the violence of the image in order to topple our understanding of visualizing women? Is this even possible in our context?

Kahil: I think this applies to what happened with my series In Your Home as it went through the motions of online scrutiny. In parallel to the verbal attacks—a great majority of them attacking my body and its “unworthiness”—the original images themselves were censored and visually maimed as the story spread to online news channels. I addressed this component of the scandal by recreating the censorship over the glass of the original framed prints using spray paint or blurred vinyl. In that way, the original images remain untouched underneath the glass, but the new layer sits atop, like a bruised skin.

I’ve often noticed that most work by women that addresses sexuality, the body, femininity, or feminist notions tends to attract verbal abuse online on a superficial, denigrating level. Shaming the artist, the work, the flesh with disparaging, overtly misogynistic remarks, or “Here’s another one getting her kit off” type of way, even on reputable sites that deal with art and photography. This happened when a review of Anatomy of a Scandal was posted on the British Journal of Photography’s Facebook page. Scrolling through that page, I noticed these comments propped up whenever a link to an article about a female artist dealing with the body in her work came up. My intention with Anatomy of a Scandal was to bring to light this phenomenon, which has always existed at a macro level, but is now amplified and globally visible through social media.

Badran: Are you thinking about certain feminist artists in your practice?

Kahil: One of the first feminist artists whose work resonated with me was that of Sophie Calle, which I discovered as a young teenager growing up in Beirut. I was blown away by the intimacy of her projects, and by their accessibility. Even without any background in art history or theory, I could understand and relate to her work as a woman and as a human. I understood that you could touch your audience and make thought-provoking work through the simplest of concepts, through personal storytelling, and create a body of work that ranges from performance to photography to text. This is a line of thought that I’ve carried throughout my practice.

Rasha Kahil, Potterells Farmhouse, AL9, Hertfordshire, from the series In Your Home, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Badran: Do have any advice for young women artists who are constantly at risk of exposing themselves to the barrage of anonymous trolls online, and who must navigate the wide web of misogyny?

Kahil: It is now impossible to have an online presence, whether through social media or even just by the fact of having a website, without coming into contact with the “mass web voice,” especially if the work deals with “inflammatory” subjects—and by using that word, I am just qualifying it from the point of view of the conservative masses. But I think that having confidence in one’s work, knowing what it communicates, who its audience is and why it exists, intrinsically protects from the consequences of online onslaught and creates an immovable wall against petty banter. The most important thing I learned from being the subject of an online scandal is that it’s not personal. Actually, emails that were sent to me personally and addressed to my face were almost always encouraging and supportive. The virulent comments were the ones that were simply thrown into the mass anonymous online conversation, and thus held no weight. As artists and as women, a little scandal is no excuse not to use our voices and our work to fuel the conversation, especially in the current climate.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.