Open Roads & Invisible Borders

For their latest trek, the group drove from Lagos to Sarajevo, a bold endeavor that would test their resolve. An excerpt from “Odyssey,” the Spring 2016 issue of Aperture magazine.

Emeka Okereke, Waiting, Rosso (Mauritania–Senegal border), 2014

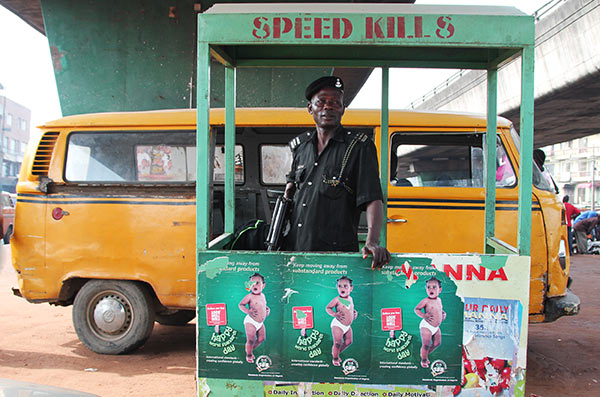

In early November of 2009, a group of ten Nigerian friends—among them photographers Uche Okpa-Iroha, Amaize Ojeikere, Emeka Okereke, and Ray Daniels Okeugo—piled into a black VW van christened “Black Maria” and headed east out of Lagos on the coastal expressway toward neighboring Benin. Their plan: to spend four days driving a 1,400-mile route from their home city to Bamako, the capital of Mali, where they intended to catch the opening of the eighth edition of the Bamako Encounters, Africa’s most important photography biennial. Four days to drive roughly the same distance separating New York from Miami. Plotted on a map it looks easy. But maps don’t account for muddy quagmires that sometimes pass as roads in the tropics, nor do they anticipate delays posed by lethargic and corrupt immigration officials staffing West Africa’s many border checks. Maps simplify reality; they can make the foolhardy seem doable.

A week after they embarked on their overland journey across Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Ghana, and Burkina Faso to Mali, the group of travelers participating in the inaugural road trip of the Invisible Borders Trans-African Photographers Organisation, an artist-led nonprofit that has now coordinated five completed expeditions, arrived in Bamako by interstate bus. Despite a breakdown in Accra, the Ghanaian capital, they had made it, albeit three days late. Bamako’s collegial photography biennial, which that year was thematically concerned with material and symbolic borders, was, however, still in full swing.

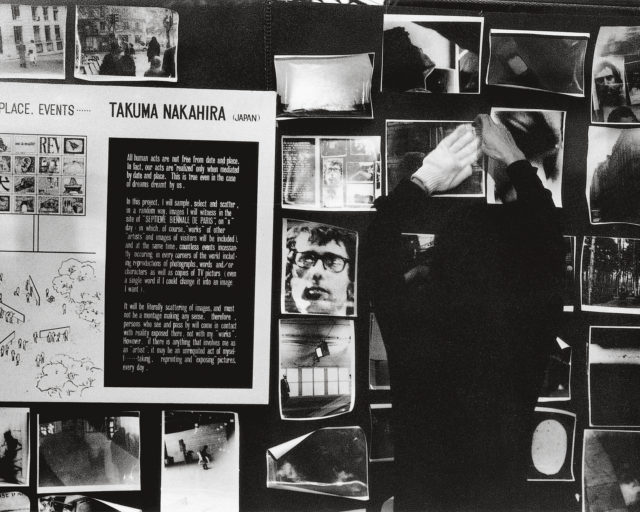

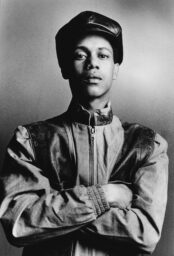

Ray Daniels Okeugo, Nna Olopa, Lagos, Nigeria, 2011

Unbeknownst to the travelers, during their journey their episodic blog had gained a small reading public among the photographic community gathered in Bamako. Predating the launch of the photo-sharing app Instagram by a year, their blog, which is still accessible online, is surprisingly text heavy. Updated by various members, notably the poet and writer Nike Adesuyi-Ojeikere, it detailed the group’s various encounters with feckless moneychangers and helpful strangers. It also chronicled the group’s cumulative frustrations as it navigated spatial and temporal thresholds, and crossed political and psychological boundaries. “We took off like a bunch of novices and thought we would be allowed to cross borders without a thorough explanation,” Okereke told me in 2012. The group’s idealism was dashed at Seme, a border post between Nigeria and Benin, where, Adesuyi-Ojeikere writes, they were held up for two hours and paid “official and unofficial taxes” before continuing.

By the time their van broke down in Accra, the group’s enthusiasm for observing Africa’s diverse realities, a core tenet of the project, waned as the “why not?” attitude that kick-started the inaugural journey ceded to the actuality of life on the road. “With no van, and living from minute to minute in the hope that the repairs would soon be done and we would hit the road again, we did not dare venture far from base,” remarked Unoma Giese, a former stockbroker turned artist, of the layover in Accra. The constraints of travel, she continued, demanded a continual regrouping and rearranging of priorities.

Ray Daniels Okeugo, Smuggler, Koussiri (Cameroon–Chadian border), 2011

Invisible Borders is a gregarious project. It is also, notably, a durable, Afrocentric, mobile photography platform that has outgrown its early origins as an informal Lagosian thing. At heart, though, it is a sociable aggregation of like-minded photographers. Named by photographer Uche James-Iroha, a participant in the first trip, this organization traces its origins back to an earlier photographic collective. In 2001, following their participation in that year’s edition of the Bamako Encounters, four Lagos-based friends—including James-Iroha and Ojeikere, son of the famed Nigerian portrait photographer J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere—founded Depth of Field (DOP), a loose affiliation of individuals rather than an aesthetic movement bounded by a common style. The collective later expanded to include Emeka Okereke, the current artistic director of Invisible Borders.

The remit of DOP’s photography was diverse, ranging in subject from James-Iroha’s allegorical portraiture to Ojeikere’s abstracted documentary studies of market goods and Okereke’s more naturalistic observations of urban soccer. After a brief flurry of exhibitions in Berlin, London, and New York in the mid-aughts, the collective’s momentum dissipated, prompting Okereke to act. “He felt that they were not doing enough artistically and project-wise to further their initial success,” says Akinbode Akinbiyi, a Berlin-based Nigerian photographer who is a key mentor and ally of the group. “Initially he launched the idea of the intercontinental travels to his closest colleagues in DOP.” They liked his idea. The maiden journey of Invisible Borders included three DOP members.

The warm response to the 2009 road trip project prompted Okereke to develop it into an annual event. In 2010, a journey was undertaken from Lagos to Dakar, the Senegalese capital city and host, since 1992, of Dak’Art, a visual arts biennial. Departing once again along the trans–West Africa coastal highway, the road trip included visits to Cotonou, Lomé, Accra, and Abidjan, before detouring inland to Bamako, bypassing the troubled states of Liberia and Sierra Leone. At Diéma, a Malian settlement between Bamako and Dakar, the group met three Nigerian women operating a roadside eatery, which they had opened after a smuggler abandoned them while en route to Spain. As was custom early on, a group portrait was produced of the Nigerian adventurers with their enterprising compatriots.

Ala Kheir, Equilibrium, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011. All photographs © the artists and courtesy Invisible Borders

In its earliest iterations, Invisible Borders was overwhelmingly Nigerian in its makeup. Since 2011, however, when the group navigated overland from Lagos to Addis Ababa in Ethiopia to join the Addis Foto Fest (with one flight connection between N’Djamena, Chad, to the Sudanese capital city of Khartoum), they have taken on a more pan-African appearance. “It began with what seemed like a Nigerian collective, but the main idea is to make it a platform for artists from different parts of the African continent,” Okereke explained in 2012.

At the time, he was planning a fourth trip: from Lagos to Lubumbashi, a mineral-rich city in the south of the Democratic Republic of Congo and site of the Lubumbashi Biennale. This southerly trip, which included participants from Equatorial Guinea, Mozambique, Rwanda, and South Africa, was marked by an epic five-day struggle on muddy roads between Calabar, a city in southern Nigeria, and Mamfe, in neighboring Cameroon. Encountering roads of thick, golden-brown clay, they hired “mud workers” to aid their passages, and later argued with officials who imposed a fine when a vehicle owned by a Chinese construction outfit collided with them. The last-minute postponement of the Lubumbashi Biennale saw the trip rerouted to the port city of Libreville, Gabon, where participant Jide Odukoya, from Nigeria, made a portrait series of his expatriate countrymen living in this oil-rich state. By this time only Okereke and Ray Daniels Okeugo, a photographer and Nollywood actor who died in October 2013, remained of the original group of ten Nigerian friends who founded Invisible Borders.

The group’s malleable membership is less important than its modus operandi, which by 2011 had matured from spontaneous adventurism into a sustained exercise in transcontinental networking and photographic encounter. The latter action, to photograph, is an important facet of the collective, but also possibly the hardest thing to coherently track. Their work is widely and consistently exhibited—including appearances in The Idea of Africa (re-invented), a 2010 photography exhibition at Kunsthalle Bern, Switzerland; The Ungovernables, the 2012 New Museum Triennial in New York; and All the World’s Futures, curator Okwui Enwezor’s exhibition at the 2015 Venice Biennale—but it is somewhat misleading to speak of an Invisible Borders style.

Often thought of as a photographic collective, Invisible Borders has evolved to include video, site-specific performances, and a good deal of writing. Although diverse, this creative output is linked by an impressionistic and sensorial thread, exemplified by Nigerian author Emmanuel Iduma’s blog posts and South African filmmaker Lesedi Mogoatlhe’s short web clip of Cameroon-based singer Danielle Eog Makedah. However, for the group’s career-defining Venice showcase, Okereke—assisted by Akinbiyi, Iduma, and photographer Jumoke Sanwo—emphasized the group’s lens-based work. Multiplicity and diversity trumped the discrete image in their photographic selection: a collage of densely clustered reportage, documentary, and pictorial images represented Invisible Borders.

To continue reading the full article, buy Issue 222, Spring 2016, “Odyssey” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.