Desire and Loss, from Stonewall to the AIDS Crisis

Pacifico Sliano, Boundless Blue, 2019

Courtesy the artist and Bronx Museum of the Arts

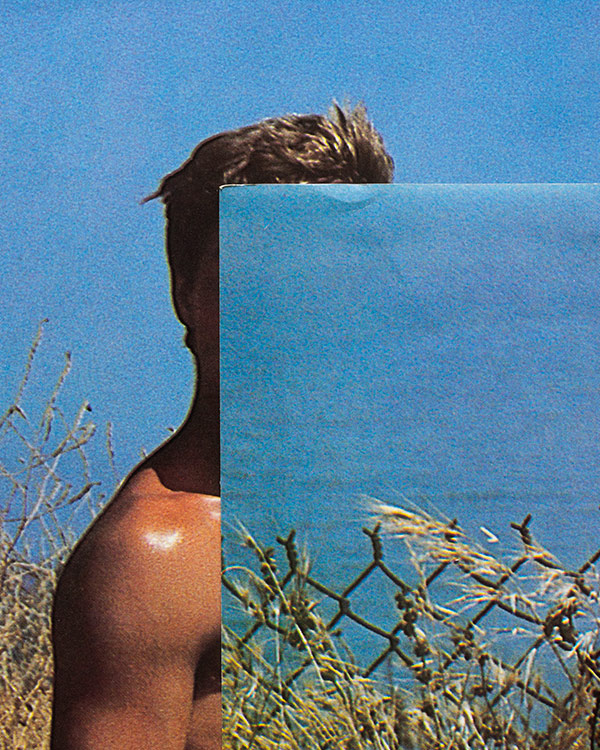

Fragments of bodies—a gently draped hand, the slope of a bicep, a wedge of exposed chest—emerge from fields of vibrant color in Pacifico Silano’s Speaking Little, Perhaps Not a Word. These large-scale photographs, on view at the Bronx Museum’s new Block Gallery in Tribeca, are composed from layers of ephemera sourced from gay erotica and pornography produced between the Stonewall riots of 1969 and the peak of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s.

The simultaneity of queer desire and loss is inextricable from these images. Silano works with his own personal collection, as well as with the late Whitney curator Richard Marshall’s archive (recently acquired by New York University’s Fales Library). While he often researches the lives of the male models and porn stars pictured, Silano obscures their identities and withholds narrative details. Many of the men pictured likely died as a result of AIDS-related complications. However, the impossibility of ascertaining further information about their fate foregrounds a more ephemeral absence.

Silano situates the viewer in the same position as the publications’ original consumers, many of whom may have also passed, and whom we become aware of through the traces of handling that remain on the page. Re-photographing these remnants is a means for Silano to put his own identity into historical context; yet, embedded within the artistic process, this becomes more than just viewing. It becomes a reparative act steeped in a deep commitment to understanding how trauma and queer identity commingle.

Pacifico Sliano, Leather Shine, 2019

Courtesy the artist and Bronx Museum of the Arts

Over the course of nearly a decade, Silano has developed a photographic practice to elevate those lost not only at the height of the epidemic, but also by the systematic suppression and erasure of the archives that contain their memory. Silano himself encountered censorship just last year, when municipal officials asked him to remove images deemed too suggestive from a public commission along the beach walk in Bal Harbour, Florida. Instead of complying, Silano withdrew from the project, thus curtailing the programming planned to build visibility and public dialogue in Miami-Dade, the county with the highest rate of new HIV diagnoses in the country.

Silano’s exploration of loss is by no means devoid of pleasure. What Silano has accomplished in these works is a deft sleight of hand, redirecting the object of our desire from sexual gratification to something more elusive. At a distance, his photographs draw us in with ebullient color, merging expanses of blue sky and glistening boulders with the soft curves of men’s bodies. Up close, a lace-like pattern of interlocking dots, vestiges of the now-obsolete offset printing process, overtake the compositional field. An errant staple, a dog-eared corner, or a shadow cast by a slight crease interrupts the mechanical artifacts with the mark of human touch.

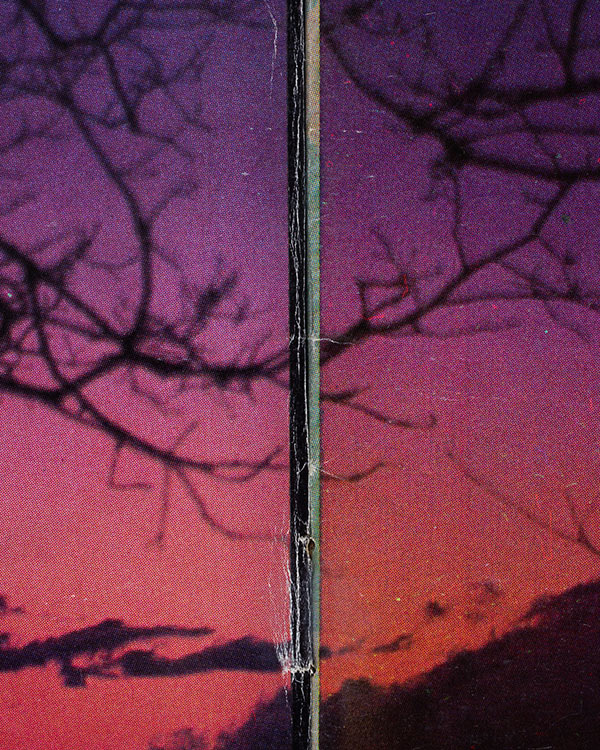

At forty-by-fifty inches, the scale of enlargement shifts the images towards abstraction. The materiality of the printed page becomes engrossing, locking the viewer into meditative study of subtle collisions of color and texture. In At Twilight (2019), which is void of the human figure entirely, a blue-grey slit bisects the center of the image, cutting across the gradient of purples and oranges surrounding the sunset silhouette of outstretched branches. The folds and creases that run along the magazine’s spine break apart the continuity of the image. For a moment, one slips away from longing to recuperate the lives of unknowable figures, to the rapt exploration of formal elements. This shift of focus offers a visual respite from the weight of grief.

Pacifico Sliano, At Twilight, 2019

Courtesy the artist and Bronx Museum of the Arts

Sodomy between consenting adults in private was not decriminalized at the federal level until the 2003 Supreme Court case Lawrence v. Texas. With this ruling some kinds of gay sex gained constitutional protections; however, people living with HIV could still be held criminally liable simply for having sex. In 1986, states began passing HIV-specific legislation intended to criminalize a broad range of consensual sexual activities based on the potential for HIV exposure, regardless of actual risk or transmission. In addition to HIV nondisclosure laws, sentencing enhancements were passed that apply more severe punishment to crimes committed by people living with HIV, based solely on their health status. In following decades, substantial medical advancements have furthered understanding of how the virus is transmitted, and increased accessibility to treatment options and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has effectively reduced the risk of sexual transmission to zero.

Despite the fact that HIV no longer poses the same deadly threat that it once did, thirty-four states still have HIV-specific legislation and/or sentencing enhancements on the books. Some states, including New York, do not have HIV-specific criminal laws, but do have legal precedents for prosecuting people living with HIV for potentially exposing another under general criminal law statutes. In New York, people living with HIV within the criminal justice system can lose their right to medical confidentiality, and be fined for violating public health laws and subjected to indefinite civil commitment, where the state involuntarily detains someone deemed “sexually dangerous,” not as punishment for crimes committed, but as a preventative measure against future crimes.

Pacifico Sliano, Blue Void, 2019

Courtesy the artist and Bronx Museum of the Arts

Silano’s tight control of the photographic medium operates as an anchor to the present, rooting the viewer firmly in the act of looking. Speaking Little, Perhaps Not A Word is not an exhibition about the history of the AIDS crisis, but rather about the living impact of the epidemic on contemporary lives. Like the traces of men’s figures that shift across Silano’s compositions, the escalating fear at the height of the public health crisis left behind tangible artifacts that we are still grappling with today.

As we celebrate Stonewall’s fiftieth anniversary this month, and the legislative gains that have decriminalized certain kinds of gay sex, we cannot lose sight of the scope of consensual sex practices that are still subjected to severe policing and punishment. Speaking Little, Perhaps Not A Word is a timely exhibition that meditates on the complexities of queer desire—especially how legacies of loss merge with pleasure to form new languages of queer eroticism. Not only can one get lost in the narrative history behind Silano’s photographs, but also in their seductive shapes, colors, and forms. This careful balance of melancholy and grace creates a powerful space for contemplation. Within it, we can find the necessary nourishment to take on the next fight.

Pacifico Silano: Speaking Little, Perhaps Not a Word is on view at the Bronx Museum’s Block Gallery through June 29, 2019.