Paolo Di Paolo’s Paradise Found

An Italian photographer of Hollywood stars, now in his 90s, finally makes his debut.

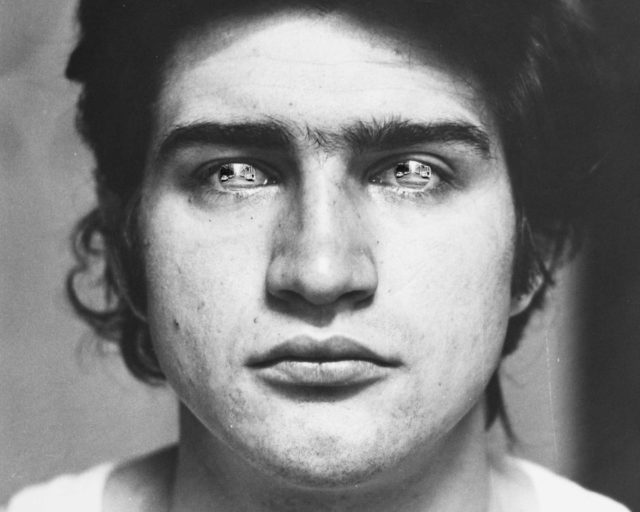

Paolo Di Paolo, Anna Magnani at her villa in San Felice Circeo, Rome, 1955

“For pleasure,” Paolo Di Paolo, the ninety-four-year-old Italian master of photography, explains when asked the intention behind his 1950s and ’60s portrayal of Hollywood stars and key personalities of the Italian art, fashion, and cinematography worlds. Decades later, Di Paolo’s unseen archive of photographs “born out of boredom” is a testament to a socially and politically capricious period in time, when Italy was coming out of the stupor and mental ferment of the Second World War. In his own special way, Di Paolo—a best-loved photographer for the acclaimed Il Mondo magazine, where he published more than five hundred photographs—witnessed and documented all layers of society in their hopes and contradictions.

Di Paolo’s first exhibition, Mondo Perduto (Lost World), currently on view at the Spazio Extra MAXXI in Rome, brings together more than 250 images, many of them previously unseen—part of an immense archive found by chance by his daughter, Silvia, in a cellar about twenty years ago. “Can you imagine my face, when instead of a pair of skis I was looking for in my parents’ home, I found these photos made by my father?” says Silvia Di Paolo, “It took more than twenty years to convince him to show these photos to the world.”

Shortly after the closure of Il Mondo in 1966, Di Paolo, feeling that he was “no longer in tune with the times, with the society that was coming into being,” abandoned his camera and, at forty-one years old, returned to his philosophical studies and the publishing world, launching a collaboration with the Carabinieri, the national gendarmerie of Italy, for which he edited around twenty books and forty-three calendars—his inestimable archive ending up forgotten in a cellar. “It must be understood in relation to a new era, a society that was being transformed,” Di Paolo explains. “At a certain time, Italy had embarked upon a new Renaissance in form and spirit after twenty years of utter darkness. The strength and enthusiasm that motivated us young people was overwhelming: Our happiness was intoxicating. When I decided to give up photography, a career that had allowed me to express fully the joy of being part of a creative society during that happy time, it felt like waking up from a dream and being anxious.”

Curated by Giovanna Calvenzi, Mondo Perduto is organized into five different segments to intersect and establish dialogue with another. All the photographs in the exhibition seem to be cosmically tethered to one another. The first segment, “Society/Rome,” focuses on the city emerging from the poverty and illiteracy of the ’50s and the sparkling international high society frequenting the capital, while the second, “Society/World,” features impressive shots from Di Paolo’s reportage in Japan, Iran, and New York.

With each of his portrait subjects, Di Paolo created a relationship based on empathy, trust, and collaboration. “Artist/Intellectuals” shows the private and intimate moments of film stars, writers, artists, and aristocrats, to whom he was granted access through his personal relationships. Whether it is enigmatic director Pier Paolo Pasolini visiting Monte dei Cocci—where ancient Romans built a hill by methodically piling up broken oil jars—actress Kim Novak ironing in her room at the Grand Hotel, or director Michelangelo Antonioni walking while reading a newspaper, each Di Paolo image embodies an acute sense of Zen, signaling an almost mystic bond between the photographer and the subject. It’s hard not to feel the chemistry as a viewer.

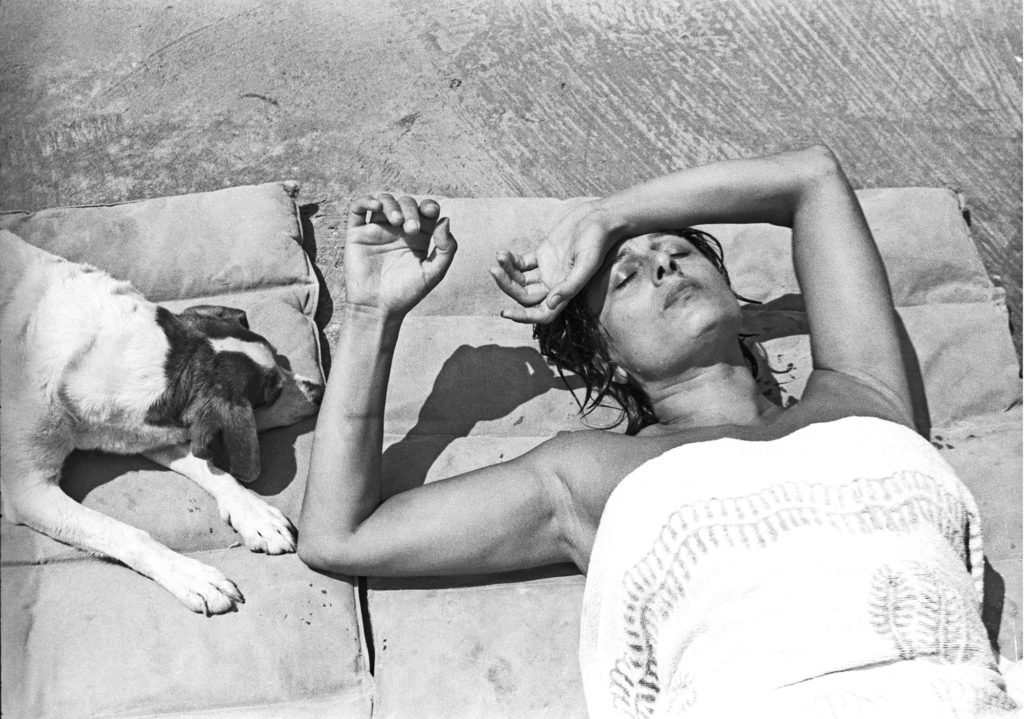

A special group of pictures in the “Film” segment is dedicated to Italian actress Anna Magnani. Another group is devoted to Pasolini, and fully expresses the director’s complex psyche. Pasolini was portrayed at the tomb of philosopher Antonio Gramsci in the Non-Catholic Cemetery, at home with his mother and, in Basilicata, and on the film set of Il Vangelo secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to St. Matthew, 1964), where Di Paolo was the only photographer allowed. These portraits lead to another group of photographs from La Lunga Strada di Sabbia (The Long Road of Sand), a travel journal from 1959 documenting Italian seaside resorts. Here, the magazine Successo, edited by Arturo Tofanelli, had the idea for an innovative pairing of Di Paolo and Pasolini for the project. One of the most iconic images portrays Pasolini walking on the Cinquale beach in Viareggio, Tuscany, while observing young bathers.

All images © Archivio Paolo Di Paolo

Di Paolo sounds amazed when asked about the attention and positive feedback the exhibition has been receiving. “The audience members have proven to be more sensitive than one might have thought,” he muses, upon hearing that the exhibition has been extended for three additional months. “Visitors who didn’t live through that happy period in Italian society still recognized that that period was responsible for shaping them—that they owe a debt to my generation based on pride in their ancestry. That was an intoxicating surprise to discover. A large audience had discovered my lost world and experienced it with pleasure and felt that they were its rightful heirs.” Mondo Perduto offers a lucid and privileged journey in time to Di Paolo’s masterfully captured moods, characters, vanity, and most of all, truth. It is indeed hard not to find pleasure in that.

Paolo di Paolo. Mondo Perduto is on view at Spazio Extra MAXXI, Rome, through September 1, 2019.