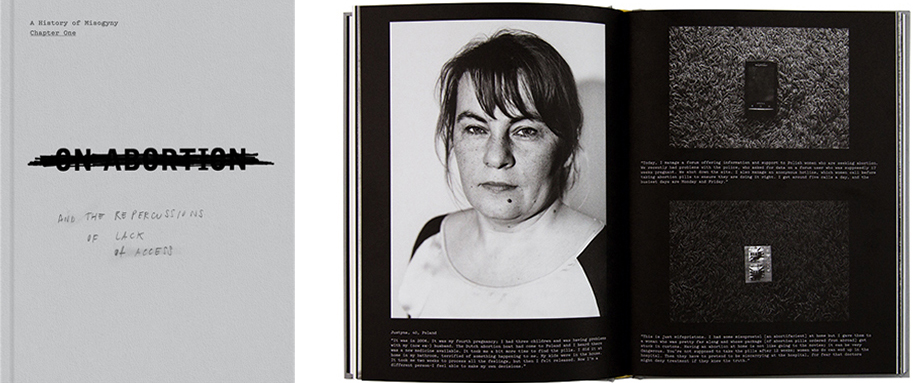

Laia Abril, Portrait of Magdalena, 32, Poland, from On Abortion (Dewi Lewis Publishing), 2018

Every year, forty-seven thousand women die from botched illegal abortions. On the front cover of Spanish photographer Laia Abril’s excellent new book on the subject, the official title, On Abortion, is vigorously crossed out in black marker and below, handwritten in pencil, is the essential problem: “the repercussions of lack of access.” It is not abortion itself, but barriers to access—laws, secrecy, shame—that cause these deaths and innumerable other tragedies for women and their families. The series title at the top magnifies the project’s scope even further: “A History of Misogyny, Chapter One.” Misogyny is a chronicle with many, many chapters, and the control of women’s fertility is one of its canonical texts.

How can photography reveal hidden histories? One strategy that artists have used is to reconstruct narratives or fill in overlooked chapters of history using archives and found photographs. But what about stories that are so secret that they were never photographed in the first place? Abril, first trained as a journalist, came to the conclusion that conventional reportage was too limited and confining a strategy for telling the stories she wanted to tell. In On Abortion (Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2018), a wrenching and beautifully designed book, she takes on the ambitious—and radical—project of making invisible histories visible.

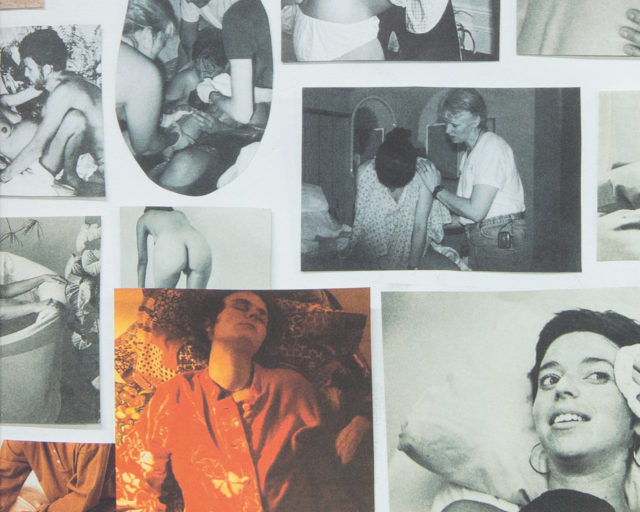

The book opens to endpapers made up of nineteenth-century advertisements for abortion and fertility cures for “married ladies” who “wish to be treated for obstruction of their monthly period.” These are bracketed by more recent color ads from Peru with offers to treat the same ancient malady, using the same euphemistic wording, over a century later. In between these endpapers is a painstaking recounting that peels away the layers of pretense and hypocrisy that have rendered this enduring history obscure.

A series of objects from a medical museum, many of which look like torture devices, demonstrate the ancient and gruesomely inventive history of fertility control. These still lifes are followed by profiles of women who survived illegal abortions. Their unabashed frontal portraits stand in contrast to the heavily blurred faces of women who died from their botched abortions. It is a subtle but profound design gesture that draws a distinction between participating subjects (the brave women who have chosen to partner in Abril’s project of demystification) and those who are powerless to consent to the use of their images. Abril also includes photographs that she staged or recreated based on documented cases. The book’s rigorously ethical treatment of vulnerable subjects, combined with its disregard for the conventions of documentary photography, offers an updated and useful model for photographers grappling with the ethics of representation, who are often overly concerned with technical issues and not concerned enough with the impact on those photographed.

Interspersed throughout are photographs that piece the overarching story together: methods of self-induced abortion, mug shots of early twentieth-century abortion providers, a drone that airlifts abortion pills into countries where they are outlawed, and the ultrasound of a nine-year-old Nicaraguan girl raped by her own father and denied a termination of her pregnancy. Each episode in this history is treated with a distinctive design solution—different paper stocks and sizes, unfolding flaps and layers—which keeps the viewer engrossed in what could otherwise be an unrelenting experience. On Abortion first appeared in exhibition form, a fact that contributed to the book’s inventive and experimental design.

While the book is detailed, it is not especially graphic, a surprise given the long history of weaponized photographs on both sides of the abortion debate. Where violent images are used, they are heavily altered. At the book’s center, in a section called “Visual War,” is a vivid red color photograph of an aborted fetus from an anti-abortion website, pixelated to the point of abstraction. Lift that photograph and you find another iconic image: the naked body of Geraldine Santoro, face down in a hotel room after bleeding to death from a botched abortion attempt in 1964. This black-and-white crime scene photo became an icon of the American pro-choice movement, and has appeared in every edition of the women’s health bible Our Bodies, Ourselves. The chilling photograph accompanies the rallying cry that “we won’t go back” to the time of back-alley abortions, when deaths like Santoro’s were all too common. Abril has chosen to reproduce the image so faintly that it is barely visible—easily legible if it is burned into your consciousness, as it is for many American women, but otherwise more idea than image, only readable because of its accompanying caption.

All photographs courtesy the artist and Dewi Lewis Publishing

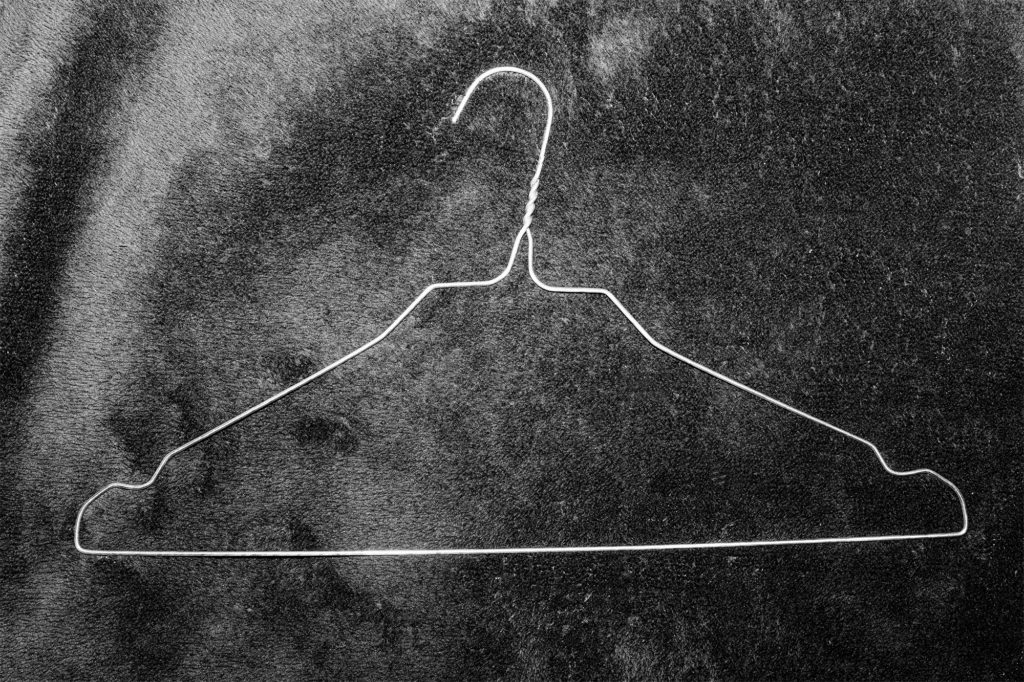

Abril says that her project aims to “visualize the comparison between the present and the past, so we understand that things are not as certain as we think—so we don’t forget what is in the past and don’t get too comfortable in the present.” In the United States, where hard-won abortion rights are being eroded, the wire hanger has become a symbol whose referent has largely faded from our collective memory. Abril’s absorbing, galvanizing, and beautifully constructed book is a timely reminder of what is at stake—not just here in the United States, but globally.

This piece originally appeared in The PhotoBook Review, Issue 014.