What is a Photo-Text Book?

Larry Sultan, Business Page, 1984, from the book Pictures from Home (Abrams, 1992)

Courtesy Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco and Estate of Larry Sultan

Quite literally, it is a book where photographs and words share equal ontological dignity, or, less academically, equal importance in contributing to the narrative of the project and where text is not a mere introduction, postface, or essay on the photoworks. Perhaps it is the ultimate nightmare for all the iconophobic writers and textophobic photographers out there.

Let’s consider two examples: the twenty-four-volume New York Edition of Henry James’s fiction, published by Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1907–9, with a photogravure frontispiece for each volume by Alvin Langdon Coburn; and the first edition of Robert Frank’s photobook Les Américains, published by Robert Delpire in 1958. James’s fear that a too-detailed image would overwhelm the retina of the reader, killing their imagination and disturbing his own literary picture, led him to give the then young Coburn strict instructions. Human figures were forbidden. James wanted the pictures to be “not competitive and obvious,” but ambiguous and general, “to shroud their documentary quality,” in the words of Ralph F. Bogardus; James desired them to work well as “mere optical symbols or echoes, expressions of no particular thing in the text,” serving as “empty” images that “the reader must fill out through their own imaginative and interpretive activity,” Bogardus notes in Pictures and Text (UMI Research Press, 1984).

At the other end of the spectrum, as Roger Hargreaves compellingly recounts in his contribution to the Photocaptionist column Image-Text Photobooks in a Nutshell (ITPIAN), the true first edition of Frank’s The Americans was swarming with text, in French, edited by poet Alain Bosquet and showing “a decidedly European take on contemporary America.” Hargreaves describes the heavily textual first edition as “a rare example of a photobook buried inside another book” and as “a cautionary tale of the potential failure of text to work with images.” He praises the replacement of the texts, for him clearly an awkward presence, with a dedicated Jack Kerouac essay as a happy solution, when The Americans was printed stateside a year later.

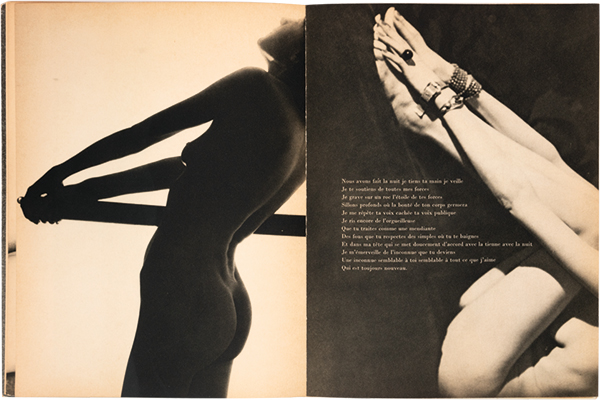

Man Ray and Paul Éluard, Facile, Éditions G.L.M., Paris, 1935

Another sign of textophobia was spotted by Patrizia Di Bello and Shamoon Zamir in their brilliant introduction to The Photobook: From Talbot to Ruscha and Beyond (I. B. Tauris, 2012). In particular, they shed light on the curious contradiction between Martin Parr and Gerry Badger’s definition of the photobook as “a book—with or without text—where the work’s primary message is carried by photographs,” presented in their acclaimed trilogy The Photobook: A History (Phaidon, 2004, 2006, and 2014), and their inclusion, nonetheless, of “too many examples” of books where text plays a fundamental role, such as Walker Evans and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor’s An American Exodus (1939), and Bertolt Brecht’s Kriegsfibel (War primer, 1955). “Photography and text always interact, even if the text is mostly elsewhere,” write Di Bello and Zamir. “They work within a dialectical relationship.” My deus ex machina helping me come through this diplomatic tussle hopefully unscathed is Lesley A. Martin, who, in her piece in the Photobook Phenomenon catalogue (Editorial RM, 2017), “Invitation to a Taxonomy of the Contemporary Photobook,” announces that “the seeds are currently being sown for the ‘genre-fication’ of the photobook” and elaborates on a number of taxonomical pathways or tracks.

Paul Strand, Worker at the Co-op, Luzzara, Italy, 1953, from the book Un Paese (Giulio Einaudi Editore, 1955)

© Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation

So, here’s my proposition: the photo-text book is a distinct and diverse species within the larger genre of the photobook that deserves proper scrutiny, precisely to transform the above phobias into philias. While it is true that words can narrow and direct the meaning of an image (the Latin origin of the term caption means “seizure”), when they exert the function that Roland Barthes defines in Image, Music, Text (1977) as “anchorage,” it is also true that they can enhance the image’s ambiguity and operate as “relay.” Don’t get me wrong: purely visual photobooks are bliss, but the idea here is to show that photo-text books don’t bite; they are just a specific category that offers the opportunity to expand the audience of the photobook beyond its own bubble, as I touch upon in my Editor’s Note.

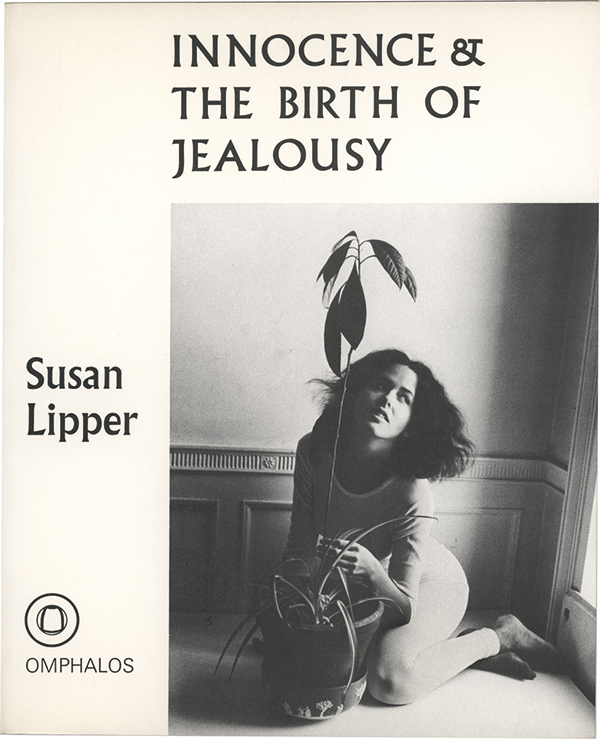

Susan Lipper, Innocence & the Birth of Jealousy, Omphalos Press, Rushden, Northamptonshire, UK, 1974

It is important to highlight that this track is not new, and its origins date way before Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. A regained momentum of “formidable hybridization that conjoins literature and photography” is undeniable, as noted by Rick Moody in his review of Teju Cole’s Blind Spot (Random House, 2017) for PBR’s issue 013, and confirmed by the amount of contemporary photo-text books presented in this issue, as well as in PBR’s previous issues. Photo-text books are deeply rooted in the history of photography. To be persuaded, we only need to look at the spate of fascinating nineteenth century photographically illustrated books, or pictorial books, as they were called at the time, in which words and images mingle more or less harmoniously; many have been recently included in great exhibitions, such as Poetic Images at both ICP (2003) and George Eastman House (2004) and Photolittérature at the Fondation Jan Michalski (2016). I believe the time is ripe to explore the track or subgenre of photo-text books, researching the past, surveilling the present, and speculating on the future.

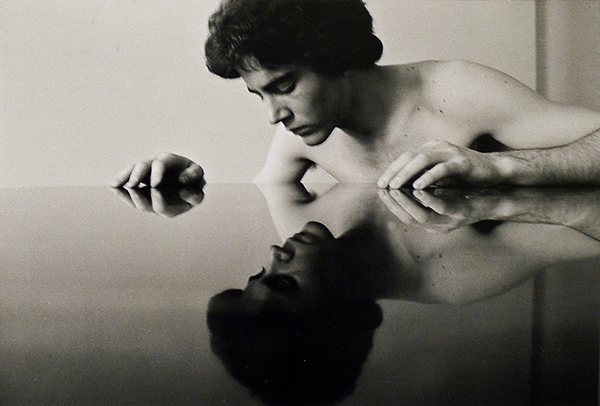

Duane Michals, Narcissus, 1974, from the book Real Dreams: Photo Stories (Addison House, 1976)

Courtesy the artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York

As I type this sort of photo-text book manifesto, I am immediately afflicted by what Thomas O. Beebee, in The Ideology of Genre (1994), describes as the paradox of genres: “they seem real and at the same time indefinable,” perhaps due to their promiscuity. Depending on the criteria we focus on, such as authorship, types of texts, or image-text dynamics, we already encounter a varied spectrum of photo-text books: collaborative versus retrospective, anthological versus monographic, photo-poetry versus photo-essay, hierarchical versus democratic, and so on and so forth. For the purpose of this introductory survey I cannot by any means even attempt exhaustion, and I am obliged to redirect you, dear reader, to my research, which combines a taxonomical investigation with a history of photo-text theory through practice and will hopefully be published in the next year or so.

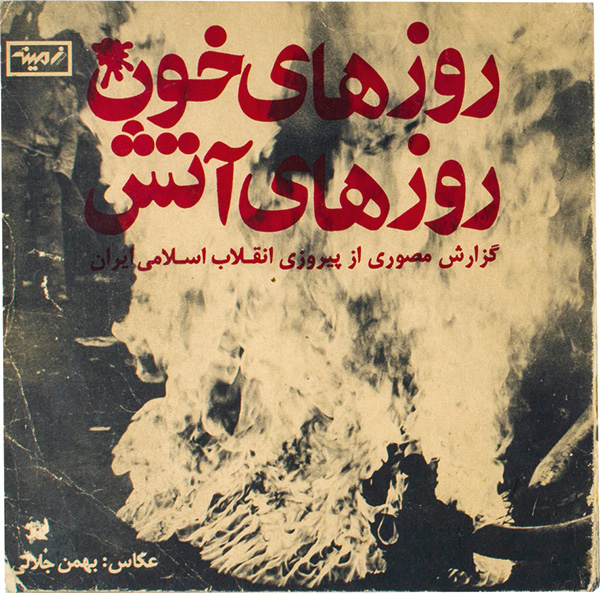

Bahman Jalali and Rana Javadi, Days of Blood, Days of Fire, Zamineh, Tehran, 1979

As a profound lover of the photobook, when I started the column on the Photocaptionist I intentionally gave it the somewhat tautological title of Image-Text Photobooks in a Nutshell. I wanted to preserve the term photobook and underline the fact that a photograph is not like any other image, but, as discussed by Umberto Eco in “Critique of the Image” (1982), it is misleadingly analogous to the retinal image. Then, I started to use “photo-text” more and more, encouraged by the introduction of the eponymous new category for the Prix du Livre given during Les Rencontres d’Arles with the support of the Jan Michalski Foundation for Writing and Literature. It’s simpler and perhaps more effective.

Recently on Facebook I read an interesting comment by photographer Vasantha Yogananthan in reply to Colin Pantall’s critique that “within photography so many people are working with the ambiguity of images and if you use a fictionalised text, there is less room for that kind of ambiguity also you need a good story. And that is difficult.” Yogananthan replied that “it depends greatly on how the fictional text relates to a sequence of images. The text could indeed be narrowing the possible readings of a picture, but (if done well) it could, on the contrary, add ambiguity/complexity to an edit/ sequence of images. That said, it is harder to do a successful photobook with text than with no text.” I agree, and I would like to take his comment as an opportunity to continue the conversation elsewhere and explore why it is harder.

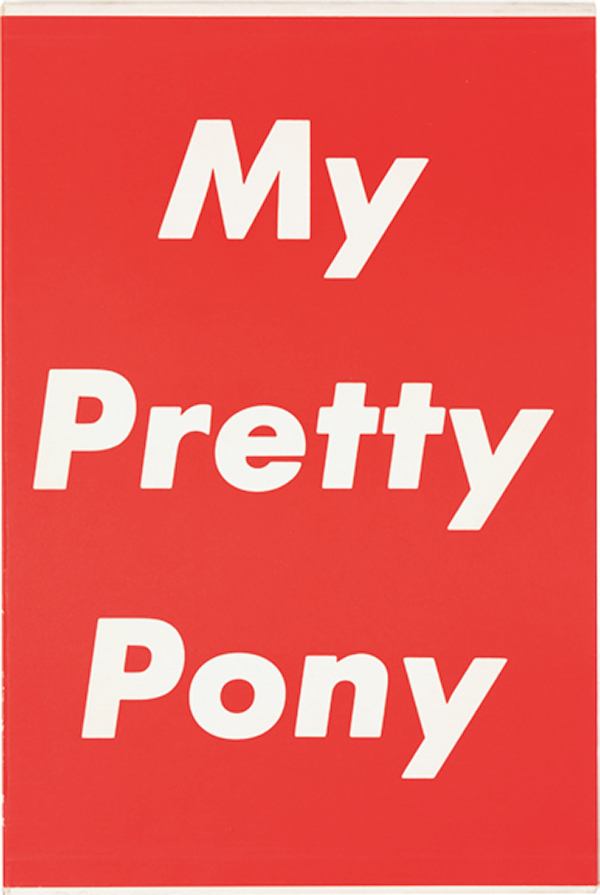

Barbara Kruger and Stephen King, My Pretty Pony, Knopf in association with Library Fellows of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1989

We have invited a chorus of scholars, photographers, curators, and writers to contribute to an annotated and incomplete bibliography of the photo-text book—titles that have laid the groundwork for this burgeoning genre, from some of the earliest offerings, as in Bruges-la-Morte, to more recent works, such as (Other) Adventures of Pinocchio. This compilation is by no means comprehensive or even consistent in its listings, but rather a first, necessarily idiosyncratic step toward exploring the genre’s diversity in all its glorious hybridity, from photo-literature to photo-poetry, through the photo-essay and more experimental compositions. It is inevitable that books have also been selected according to personal taste; additionally we have leaned toward books that are pioneering, or that have eccentric image-text dynamics, which don’t necessarily manifest in every page. We tried our best to cover a broad geographical area, within the obvious linguistic limitations of a photo-text book when its words belong to a language unknown to the reader. There are omissions of some landmark books: Rodchenko and Mayakovsky’s 1923 collaboration on Pro eto. Ei i mne (About This. To Her and to Me); Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland, Changing New York (1939); Richard Wright’s 12 Million Black Voices (1941); Manuel Álvarez Bravo and Octavio Paz’s Instante y Revelación (1982); W. G. Sebald’s The Emigrants (1992); Elisabeth Tonnard’s Two of Us (2007); Roni Horn’s Another Water (2011); and Alec Soth and Brad Zellar’s House of Coates (2014). The list goes on.

Needless to say, our efforts represent a minor scratch in the surface of future research and analysis. We would like to express our most sincere grazie mille to this issue’s contributors for their most generous participation in this photo-text extravaganza, and look forward to continued dialogues and ideas about both the history and the future of the photo-text book.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review Issue 016 or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.