The PhotoBook and the Archive

If we restrict ourselves merely to archives of photographs, the sequential succession of the book seems inherently opposed to the archive’s static taxonomy of images. An archive of categories presents its user with a map of instances, without a narrative trajectory, yet the book form implicitly suggests—and inevitably produces—a sense of progression from beginning to end. How are these opposing dynamics reconciled and transformed when the archive is rendered in the form of the photobook?

It might be that the photobook, as a physical object, reenacts the processes of interpretation implicit in the organization of the archive itself, reflecting an instinct common to the breadth of photographic practice: a need to order, and thus make sense of the changing world. Looked at this way, the photobook functions as a means to give us some purchase on what Gerry Badger describes as photography’s “endless image bank,” allowing us to revisit and rearrange history in the face of modern life’s constant flux.

The photograph’s affinity with everything from criminology to space exploration makes editors and archivists of the countless millions of us who use it. Photographs themselves have become emblematic of the flux of modern life, in both their physical and digital form. In attics and airport databases; in albums, auction houses, and super-cooled server arrays; in corporate and governmental institutions; at black sites and on the deep web, they are continually aggregated, appropriated, arranged, and abandoned at an inconceivable pace.

If it is typical of photographs to accumulate, their circulation and transfor-mation are no less intrinsic to their nature. They migrate from the low resolution of the Internet to newsprint halftone to 42-by-78-inch gelatin-silver prints; they enter new systems of collection and revaluation, eloping from the pages of pulp novels to memory sticks to the uncoated surfaces of photobooks, only to be archived all over again. The single photograph, or the original file, eventually lives on in a multiplicity of forms. The volume of photographic images in the world proves, as Adrian Searle has written, “just how much we like to look, that looking drives us where it will, that we keep on looking.” Thus, it is through the considered articulation of the archival photobook that we are able to look again at our history of seeing the world.

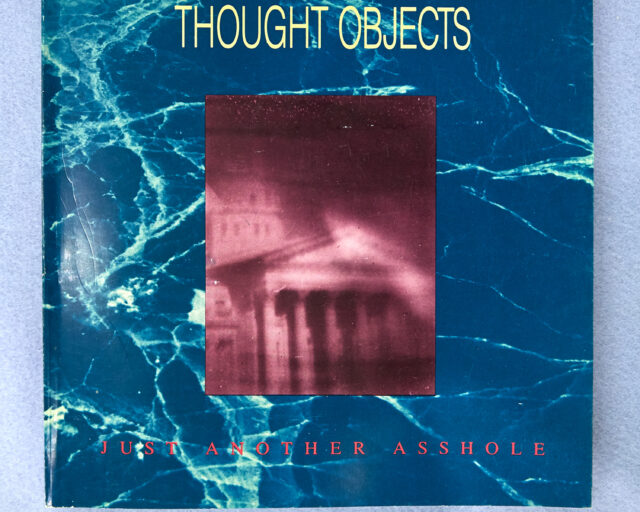

In this issue, various artists, publishers, critics, and art historians examine archival photobooks that span both the history and contemporary shape of this resurgent form of photographic activity. While limitations of space make a full accounting of this history impractical here, we are delighted to have been able to include contributions from seminal figures and relatively new practitioners, as well as show a meaningful fraction of the wide range of books produced in this vein. From works of collage to re-photography, from typological strategies to cinematic modes of appropriation, these projects celebrate the plasticity of the photographic image, and the perennially open-ended nature of those meanings, which can be reconstructed from the orderly depths of the archive itself.

It is through the considered articulation of the archival photobook that we are able to look again at our history of seeing the world.

Giorgio Agamben writes in his essay “What Is the Contemporary?” that “the entry point to the present necessarily takes the form of an archaeology; an archaeology that does not, however, regress to a historical past, but that returns to that part within the present that we are absolutely incapable of living.” The resurgence of archival projects in the photobook suggests an eagerness on the part of many artists to explore the intersections, or indeed presences, of the past in the present tense. Whether these works take the form of “an allegorizing of the past by the present, or . . . an allegorizing of the present by a past it now claims as its own,” as David Campany has written, the works shown in this issue demonstrate that the photobook is an extraordinarily adaptable form with which to reexamine the temporality of the photographic image, in all its poetic strangeness and fascinating complexity. They show us that photographs have a multiplicity of irreducibly social lives, that our histories are malleable, and that those histories might be shored up against forgetting through the patient labor of rearticulating experience in the form of the photographic book.