Photography in a World Where the Center No Longer Holds

German artists have often used typologies to help us understand the world. But an exhibition in Milan parades photography’s failures: to document, to mourn, to bend experience into arcs of narrative.

Thomas Struth, Musée du Louvre IV, Paris, 1989

© the artist and Courtesy ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe

Bernd and Hilla Becher started paying attention to the weather sometime in the late 1950s. The couple had just commenced their lifelong project of documenting the water towers, blast furnaces, coal mines, grain elevators, and other Industrial Age rejectamenta of the Ruhr, and the shadowless light and neutral backdrop of overcast skies were required for achieving the preternatural flatness they desired in their photographs. The Bechers had other rules, too: Shoot head-on, with a large-format camera. Arrange in grids or rows. No people.

© Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher and courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/Bernd and Hilla Becher Archive

By frankly depicting what was in front of them, the Bechers set themselves apart from others in the West German art world, which had largely embraced the consolations of abstraction after the unrepresentable horrors of the war. With their ostensibly plain, technical pictures, the Bechers found a way forward by looking back, bridging the uncanny verism of August Sander’s New Objectivity portraiture with the mechanized repetitions of the American avant-garde (think Minimalist sculpture and Andy Warhol’s silkscreen Marilyns). “We don’t have any message,” Bernd said. “We are only interested in the object.” The couple photographed thousands of machines and factories—obsolescing blights transmuted into totems of alien beauty—but their most compelling subject was arguably the camera itself. The reticent majesty and rational order of their inventories, in which every form correlates to a clear function, belie an uncertainty about the function of photography in a world where the center no longer holds.

Courtesy Fondazione Prada

This air of uncertainty, if not full-out melancholia, pervades Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany, an exhibition on view at the Prada Foundation in Milan. Curator Susanne Pfeiffer had first set out to make a show about the Dusseldorf School, a loosely knit group of photographers educated by the influential Bechers at the Kunstakademie during the 1970s and ’80s. Six alumni made it into Typologien—Candida Höfer, Isa Genzken, Andreas Gurksy, Simone Nieweg, and the Thomases Ruff and Struth—but the exhibition quickly outgrew its academic origins as Pfeiffer decided to mine a more general proclivity for typologies (that is, systems of classification used to organize things) among German photographers, here represented by some six hundred images by twenty-six artists.

© Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher and courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive

Courtesy Berlin University of Arts/Karl Blossfeldt Collection/Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur

Why this show now? Photographic typologies “enable a clarity of their own, which allows similarities and differences to emerge,” the curator writes, a bit mistily, in the show’s catalogue, adding that typologies’ “photographic equivalence is simple and liberating, but also disturbing, frightening.” There are no explanatory labels or thematic sections. Photographs speak for themselves, or don’t, floating in a labyrinth of artificial gray walls suspended across the hangarlike space of the Prada Foundation’s Podium. Despite a lack of argumentative thrust, Typologien can easily be read as a kind of stealth exhibition about AI, its typology of typologies issuing an elegant rejoinder to the malign systems of image- and meaning-making—our world of infinite surveillance and slop—brought about by machine vision. We could stand to invest, the show suggests, in slower, more embodied, and more unsettled ways of connecting images.

A mania for typologien first swept German photography during the Weimar era. Amid compounding postwar crises, artists and intellectuals turned to classificatory patterns as a way to impose psychological order on their infant democracy. Typecasting in interwar Germany fit hand in glove with physiognomy, the ancient practice of reading character from outward appearance. Spellbound by this pseudoscience—which extended beyond human beings to objects, nature, and even entire cities—German photographers of all political hues began to reconceive the modern camera as a facial recognition technology able to represent and simplify categories of race, class, religion, age, occupation, and politics, such that by 1927, the critic Siegfried Kracauer could remark that reality itself had assumed a “photogenic face.”

Courtesy Fondazione Prada

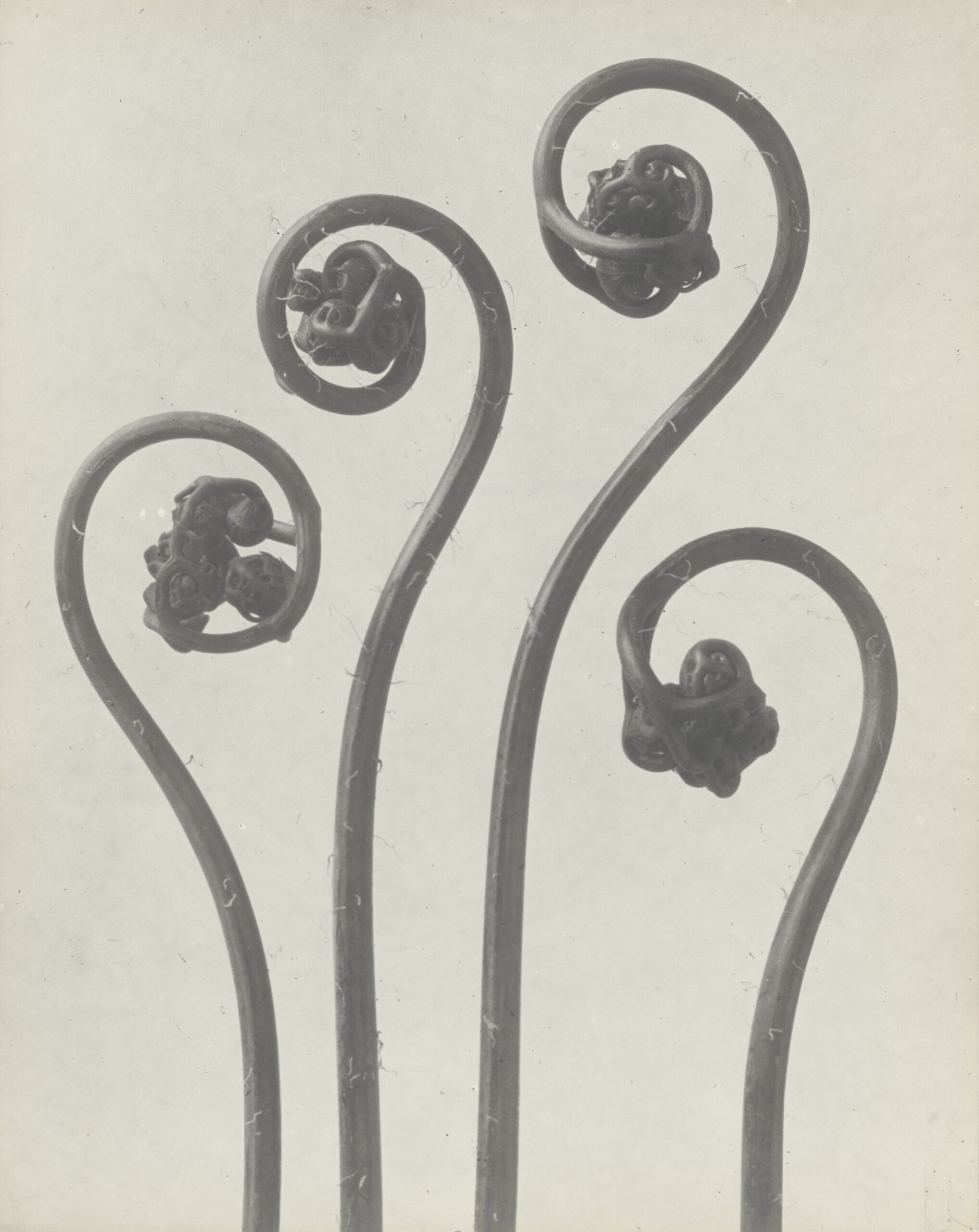

Surprisingly, portraiture is nowhere to be found on the first floor of the exhibition. It opens with Karl Blossfeldt’s gorgeous 1920s close-ups of ferns, a reminder of typology’s origins in seventeenth-century botany. These unfurling fronds, photographed in unprecedented detail with a homemade camera, neighbor the sensual orchids of Lotte Jacobi, studies of leaves by Hilla Becher, and Simone Nieweg’s late-twentieth-century photographs of neglected garden plots on the fringes of German towns. Nearby, Thomas Struth’s photographs of dew-dappled lilies, shy sunflowers, and other flowers, originally commissioned as art for hospital rooms, act as foil to Andreas Gurksy’s gargantuan 2015 aerial view of a tulip field, abstracted à la Color Field painting into machined bands of dull red, green, and brown.

In lieu of isolating types for comparative analysis, many of these artists offer variations on a theme of dispassionate obsession. Sigmar Polke’s 1966 morphology of everyday things—a black glove, a balloon, a folding ruler, etc., all ostensibly manipulated to look like palm trees—snickers at the show’s very premise, wryly deflating a German typological tradition that emerged during the Enlightenment. Candida Höfer’s forlorn menagerie of zoo animals, as with Struth’s much-celebrated photographs of museumgoers, taxonomize nothing so much as the camera’s inability to generate new sight lines within Europe’s stagnant institutions. A massive 1989 Cibachrome by Struth of tourists at the Louvre dwarfed by The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19) may be a masterpiece in its own right, but Géricault’s painting inside the photograph feels, strangely, like the more contemporary image.

© Heinrich Riebesehl/SIAE

Amid so much famous work, there are a few hidden gems. The show’s real discovery, a group of quietly wondrous photographs by Heinrich Riebesehl, records harshly lit encounters with elevator passengers over the span of a single day in 1969. Isa Genzken’s 1979 appropriations of ads for hi-tech Japanese record players—“The clean and simple truth,” goes one tagline—link the Capitalist Realist painting of 1960s Düsseldorf with the sleek cynicism of New York’s Pictures Generation. They may also bait thoughts of RAF ringleader Andreas Baader, whose 1977 suicide was carried out with a gun secreted inside his jail-cell record player. At least, that was the spin. Nine years after the dark German Autumn, Gerhard Richter included Baader’s record player in October 18 1977, a fifteen-painting cycle that portrays a gray, blurry reality where the truth is neither clean nor simple. October 18 1977 didn’t travel to Milan, but a kindred series by the underrated artist Hans-Peter Feldmann is on view. Die Toten 1967–1993 (The Dead 1967‒1993, 1996–98) depicts about ninety people who died during the wave of domestic terrorism that convulsed West Germany, a reaction, in part, against the capitalist system that brought about the country’s economic miracle, so called. Across three walls, a crawl of newspaper photographs silently tallies and ambiguates the instigators and victims of assassinations, shootouts, kidnappings, hijackings, and crossfire, a monument to national trauma as ephemeral as birdcage liner.

© Generali Foundation/Isa Genzken/SIAE

The human face is finally pulled into focus on the second floor, where the familiar subjects of August Sander’s People of the Twentieth Century greet us like the return of the repressed. Sander undertook his vast, unfinished compendium of portraits, beginning in 1928, as a way to represent the seven types of Germans—“The farmer,” “The skilled tradesman,” “The woman,” “Classes and professions,” “The artists,” “The city,” and “The last people”—who, as he saw it, made up a country undergoing an intense identity crisis. He called it the “physiognomic image of an age.”

Hindsight haunts Sander’s words, of course. The critic Allan Sekula once described the photographer’s naive vision of society as that of a “neatly arranged chessboard,” set up only for the Nazis to send it all crashing to the floor. But Sander’s triumph resides in the futility of his project: The particularity of his sitters always manages to break through whatever category he has filed them under, and the portraits astonish for their simple demonstration of how objectivity and subjectivity can exist only through each other. Each person’s anonymity, later echoed in the Bechers’ phrase “anonymous sculpture,” gains new resonance at a time when algorithmic typologies are relentlessly arrayed to create brutal regimes of identification. How to read Walter Benjamin’s 1931 description of Twentieth Century as a “training manual” for democracy and not think of the billions of AI training sets that reduce photographs to inputs and humanity to datapoints? Even so, it’s often hard to requite the gaze of Sander’s people, characters in a dream about to go bad. In 1936, the Gestapo destroyed the plates for Face of Our Time, a portfolio of sixty Twentieth Century portraits, for being insufficiently Aryan.

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archive/SIAE

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur/August Sander Archive/SIAE

Courtesy Fondazione Prada

The maze of Typologien finally deposits you into a sparse section devoted to Holocaust-related panels from Gerhard Richter’s Atlas, a vast reservoir of found pictures juxtaposing the banal with the harrowing, from sunsets and bouquets to the atrocities of Auschwitz. In this room, gridded thumbnail photographs of corpses and soldiers waver in and out of focus, some completely illegible. Begun in 1962 and still ongoing, Richter’s Atlas seems to descend from the Mnemosyne Atlas (1928–29) by the Jewish German art historian Aby Warburg (conspicuously absent in Typologien), who attempted to map the “afterlife of antiquity” through hundreds of reproductions of artworks mounted on sixty-three panels. But whereas Warburg traced how cultural remembrance is constructed through imaginative connections across time, Richter questions whether collective memory is still possible when the guarantors of truth and presence no longer sway. Yet, by hallowing this somber passage of Atlas with its own alcove and depriving it of juxtapositions with other works in the show, no doubt out of an abundance of caution, the show risks undermining Richter’s profound project, which acquires its painful meaning by treating all images as equally significant.

Typologies are intended to help us understand the world, but the works in Typologien repeatedly parade photography’s failures: to document, to mourn, to bend experience into arcs of narrative. In 1997, as Feldmann was compiling his book of the dead, Wolfgang Tillmans began photographing the Concordes screaming over Heathrow. For the artist, these Cold War symbols of tomorrow conjured “an image of the desire to overcome time and distance through technology” at the speed of sound. The airliner was retired after a 2000 crash killed more than a hundred people, lending the photographs a valedictory mood, glimpses of the future slipping into history. “The true picture of the past flits by,” Benjamin wrote in in his final essay, composed shortly before his death in flight from the Nazis. “The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized, and is never seen again.” The sentiment has been internalized by many of this show’s artists, who treat the camera not as a lepidopterist’s pin but as an instrument of unknowing, a tool to unfix our way of seeing a world that exceeds any attempts to predict or name it.

Typologien: Photography in 20th-century Germany is on view at the Fondazione Prada, Milan, through July 14, 2025.