The Expansive Power of Feminist Photobooks

In the 1990s, when I was an adolescent, a former babysitter who lived in the house behind my family’s gave me a few of her zines. Made with friends who used the copy machines at their various jobs before the arrival of the internet, they were full of photographs, mostly found but some authored, all roughly clipped and xeroxed to oblivion. In them I found a way to see.

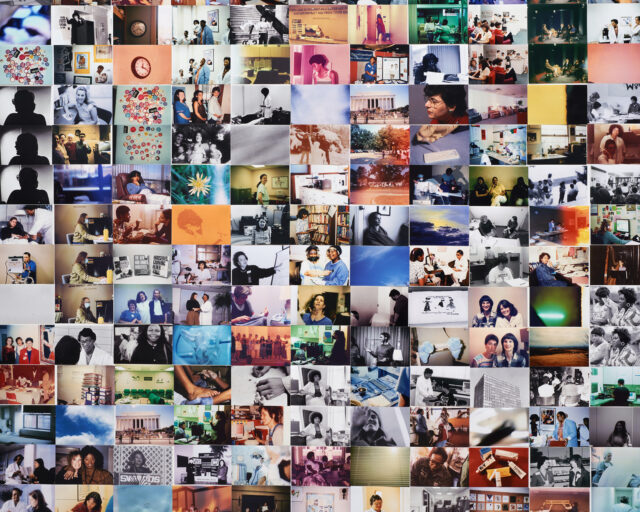

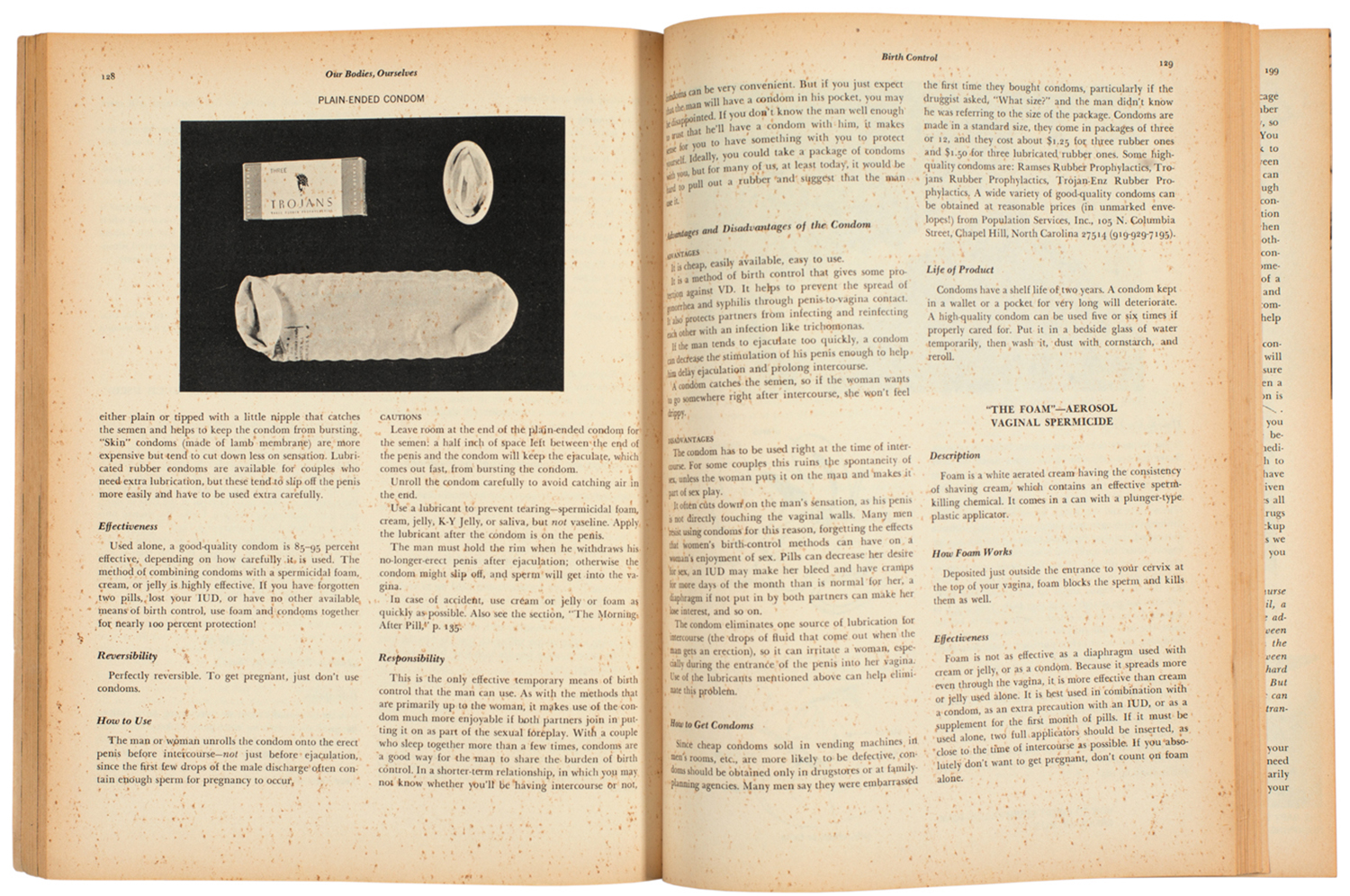

A few years later, I discovered a copy of Our Bodies, Ourselves (Simon and Schuster, 1973) on my mother’s shelf. I skipped over the text in favor of the pictures, of which there are hundreds. They appear on almost every page, many of them made by notable feminist photographers, like Suzanne Arms and Cathy Cade. When I returned to that same copy decades later, in order to cut it up for an artwork, I found myself recognizing every image and remembering how it felt to encounter them in the first place. They are striking photos—faithfully reproduced in edition after edition—and I learned from them about obstetricians, masturbation, menstruation, friendship, sex, and even dying. (In the last ten years, newer versions of the book have become frightfully sanitized.) I knew what to expect when I got a legal and safe abortion, fifteen years later; because of the pictures I had seen in that book, I was not afraid.

For the first time, I wondered: is Our Bodies, Ourselves a photobook? Is it my favorite photobook?

As I began research for this issue of The PhotoBook Review, I turned to the feminist artists that I admire, seeking out the books that they’ve made and those that have been made about them. I entered “feminist photobooks” into the internet machine, e-mailed university and museum librarians, stole long glances at people’s bookshelves. But this approach was the wrong way to begin, a reverse premise. I was sifting for content—photobooks about feminism, or, books that held feminist documents—rather than photobooks that are, in and of themselves, feminist objects. I realized I was overlooking something more nuanced about the possibility of the photobook as form in and of itself, as something that can be inexpensive, widespread, open to intervention, bound up in strategic experimentation. Once I stopped seeing the book as a container, I began to engineer the question differently—in a manner that a former mentor of mine, Larry Sultan, might have called the “inside-out approach.” Instead of asking, What feminist photobooks might you recommend?, I began to ask, What makes a photobook feminist?

Working from the inside out can be a strange task. And the question of what makes a photobook “feminist” is entangled with all sorts of creative decisions, as well as worldly ones. The choices we make as photographers and book makers—single or double spreads, quality of paper and method of design, subject matter of the images—are inexorably related to the context(s) in which that book will circulate. More than anything, I begin to answer this question through its entanglements.

In addition to their affordability, photobooks—primary objects in an art world that so often prizes the rarified, weighty, and singular—can travel. Books occupy a specialized status, something less fixed and infinitely mobile. Sara Ahmed, an incomparable feminist writer of our time, has prompted that the feminist movement is just that: something that both moves us through emotional affect, and moves us across place and time. I have thought of this idea regularly as I produce my own books, which may be tucked under an arm, held in a small bag, or sent across oceans. Ultimately, the question of what makes a photobook feminist is also a way of asking how politics, in fact, belong to form. Or can form itself have a politics?

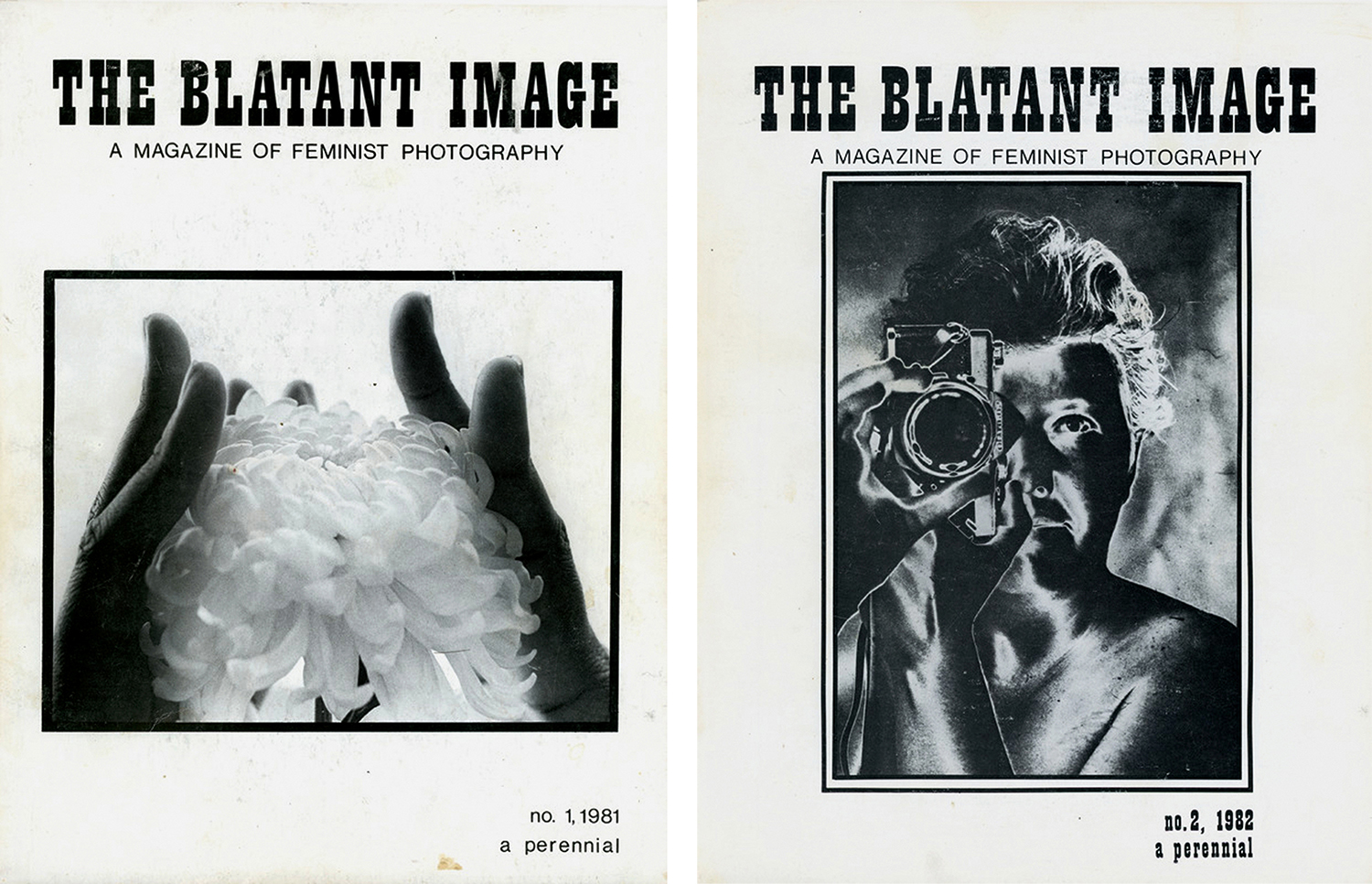

This year, I’ve been doing research for my own new photobook—Notes on Fundamental Joy, published by Printed Matter, on the photographs made by lesbian separatists in the 1980s American West—across the archives at Smith College, Cornell University, the University of Oregon, and the University of Southern California. I discovered a world of printed material, largely pamphlets and magazines, by these feminist photographers. Perhaps most widely known is The Blatant Image (1981–83), a three-issue run of a photo magazine published by Rootworks, a womyn’s land community in Oregon; in those pages, I note the very early photographic work of Barbara Hammer, Mary Beth Edelson, and Carrie Mae Weems, who appears in print for the first time.

This is not to suggest that traditional books of photography, as we might identify them, are not also keenly feminist. Books by Susan Meiselas, Gillian Wearing, Laia Abril, Carolee Schneemann, Catherine Opie, Renate Bertlmann, Hannah Wilke, Jo Spence, Lorna Simpson, and Laura Aguilar are among my most treasured possessions and have informed my own creative and political consciousness in profound ways. They, too, taught me how to see. My aim is not to distinguish and divide between kinds of photobooks, but instead to work to thread them together, or at least understand them as profoundly related, and deeply entangled, ways of working. And, of course, not all photobooks—much less photobooks made by women—are inherently feminist, but rather, and this is my anchor, the form is unique for its feminist potential. There’s a reason that feminists, from the separatists to the Magnum members, to some of the great photographers of the fine arts world, have so often found a home in this way of working, no matter their discrepant methods of doing so, locating between its covers a shared inquiry and value system.

What gives the photobook such expansive feminist potential? There is no single way to answer; the question itself only seems to yield more questions. But here are the qualities I would identify: it’s a low-cost venture in an art world that values monetary worth and physical grandiosity as a metric of success; it’s full of movement (both in how a reader may travel through it and with it); it exists in the multiple and thereby circumnavigates notions of “uniqueness” vis-a-vis value and taste; it exists as the dedicated site of action and exploration rather than documentation and afterthought. A feminist photobook affirms—for me, and I think also for the other writers across these pages—the possibilities of being an artist and of being a feminist as related and inexhaustible. I reached out to a select and diverse group of photographers, writers, and feminist thinkers for this issue, prompting each of them to respond to a particular gesture (a spread, a decision, a printed object) that enabled them to address this very possibility. Collectively and through difference, each has provided a way of addressing the potential of the print, paper, and image to pose radical statements about and for our time.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review, Issue 017, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.