The Queen Unleashed

Lyle Ashton Harris’s archive offers a queer vision of the 1980s and ’90s.

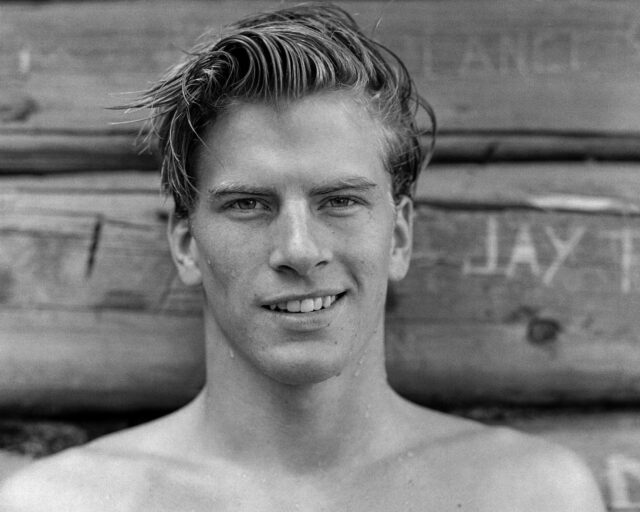

Lyle Ashton Harris, Marlon Riggs, Judith Williams, Houston A. Baker, and Jacqui Jones, Black Popular Culture conference, Dia Center for the Arts, New York, December 8–10, 1991

© the artist

Lyle remembers Marlon Riggs doing a runway walk in a dazzling white T-shirt with black letters that spelled “UNLEASH THE QUEEN.” Lyle has the photograph to prove it. I have no photograph and no memory of the T-shirt but am nonetheless certain that Marlon wore a black jacket, stood behind a podium, and daringly read a text straight from his laptop screen. Lyle didn’t photograph that performance, and so he doesn’t remember the laptop, or, for that matter, the text, which soon became the widely published “Black Macho Revisited: Reflections of a Snap! Queen.” Lyle remembers Marlon fierce, Marlon fabulous, Marlon laying claim to public space for the young and queer and black at an event for public intellectuals that leaned distinctly away from the arts toward academic discourse. I remember Marlon’s nerve. He had written his talk on the plane and had no way to present it but to read from a screen. I’d never seen a fellow procrastinator pull off that trick. It was 1991. People still used paper. Laptops were heavy. There was no easy way to scroll down a text. Marlon held his laptop in the air and managed, though his hands were a little shaky and so, just at the start, was his voice.

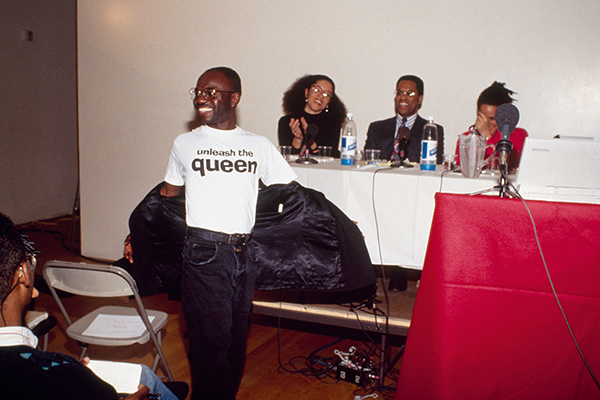

Lyle Ashton Harris, Kinshasha Holman Conwill, Black Popular Culture conference, Dia Center for the Arts, New York, 1991

© the artist

Same event, two performances (at least). Although Lyle and I are just little slices in each other’s archive, Marlon’s performance was a formative moment in our respective and respectful creative lives. It was at the Black Popular Culture conference organized by Michele Wallace and held at the Dia Center for the Arts in SoHo. I punctuate Lyle’s photographic archive as a terrible haircut on a middle-aged white woman in the audience, listening to Kinshasha Conwill, then director of the Studio Museum in Harlem. I was in row ten or so, not back row and not front either, trying to learn—which I did—while being a present but non-colonizing ally. Besides, I’m shy and I wasn’t in the in-group of speakers. Neither Lyle nor I remember exactly what Conwill said, just that she bluntly and boldly addressed some questions and discontents on the relationship between queerness, race, and representation, and that whatever she said caused a buzz of resistance. The year 1991 was a turning point for queer and for black and for mixing up those labels to contest fixed identities with a spectrum of practices, skin hues, ethnicities, and nationalities. We had gone through some of those changes together, Lyle and I. When I met him, around 1987, he had just graduated from Wesleyan and though he’d spent the summer at a well-known photography workshop program in Maine, he wasn’t yet an artist but rather a promising snow queen.

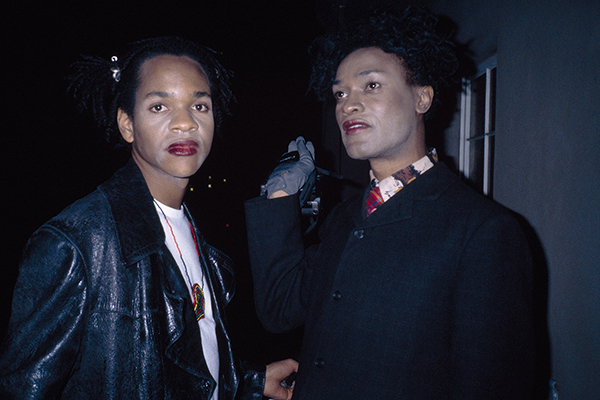

Lyle Ashton Harris, Lyle and Iké, Narcissistic Disturbance exhibition opening, Otis Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles, February 3, 1995

© the artist

While everyone else devoted themselves to rocks and the zone system, Lyle stayed in his motel bathroom screwing around with whiteface and a tutu. Those antics alone, I figured, were worth the price of admission to CalArts. As I was the dean then, I saw to it that Lyle was admitted, despite the fact that the photo faculty, then rather conservative in their distaste for anything documentary, and perhaps for young black queens with a mouth on them, was less than enchanted. In his few years as a CalArts student at the end of the 1980s, Lyle created the space he needed. As a young student, any number of clueless comments by white faculty or by other students could have stopped him in his tracks, but Lyle’s photographs show him collaging another world—rigorous in its politics of race and sexuality, insistent that pleasure was the point of the project, and cognizant that sociality was not only the way to get there but in itself a method of working that could be documented. The photographs in Lyle’s archive—which weren’t what Lyle showed faculty as his Work—were a way of offering narrative and representation to the inhabitants of the world he was helping to invent. The snapshots construct a universe of queer and color, of joy and heartbreak, haircuts and T-shirts, meds and books, beds and pets, doorknobs and drinks. Such lists put flesh on gossip, give the backstory that drives and cements subcultures. The photographs and the act of celebrating through photographs are cultural resistance. This is what intellectual history looks like.

This feature is adapted from the Aperture book Lyle Ashton Harris: Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs.

On Friday, December 15, Lyle Ashton Harris will be joined by an intergenerational group of artists and writers for a night of conversation and performance at the Whitney Museum. Tickets are available to purchase here.