Queer Photography: A Reflection

For the “Queer” issue, originally published in spring 2015, Aperture asked artists and critics to reflect on the term queer and its relationship with photography. Here, Vince Aletti recalls Tomorrow’s Man, Peter Hujar, James Dean, and the thrill of discovering queer pictures.

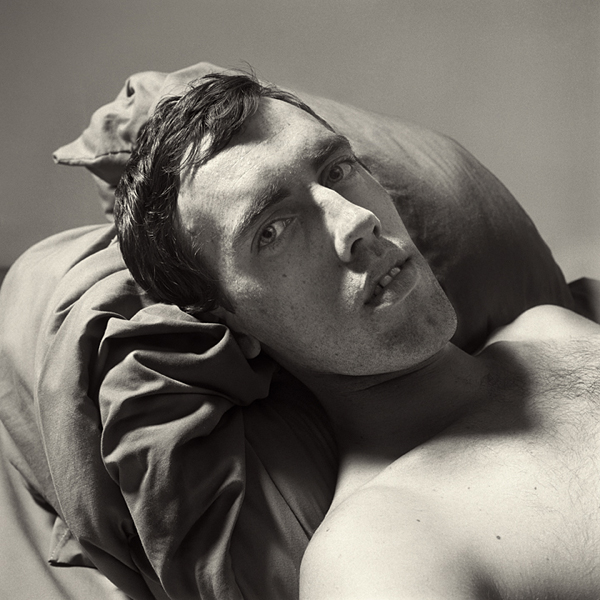

Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz, 1981 © The Peter Hujar Archive LLC

The first queer photograph I ever saw excited and confused me. It was at a newsstand in the Jersey Shore town where my family spent the week of my father’s summer vacation, sometime in the late ’50s. Tucked between bodybuilder magazines like Strength & Health were some pocket-sized pamphlets with nearly naked men on their covers and titles like Tomorrow’s Man, Body Beautiful, and Fizeek. In one of them, I came across a picture of two dark-eyed young guys—they looked like regulars on Bandstand—in nothing but stripped-down jock straps, one slung across the other’s shoulder like a trophy. It was titled Victor and Vanquished, and I stared at it, mesmerized, until my mother called me away. I had no words for what that picture meant, certainly no classical references to fall back on. I’d seen kids horsing around in the locker room at school, but I’d never imagined anything as intimate as this. Maybe because I instinctively understood the way aggression masked tenderness, there was something thrilling about two naked men holding onto one another like that—something queer.

Queer was the word kids at school used to describe sissies or guys they didn’t like. It didn’t have anything to do with sex, homo or otherwise, until I was in high school, and by that time I knew they meant people like me: perverts (another period term, not yet reclaimed). By then I’d bought and hidden a cache of those little magazines and I knew that their pictures were about sex, although I had only the vaguest idea what that meant. I’d been going to the library and looking up homosexuality in the indexes of psychology books, which usually led to dry, alarming discussions of inverts, pathologies, regression, and abnormal urges. Physique magazines countered that tone of barely disguised clinical contempt with an upbeat, celebratory take on mid-century masculinity that was deeply queer but butch enough to pass as straight. With few exceptions, however, they weren’t holding up a mirror to their readers; they were providing us with all but unattainable objects of desire: handsome, heroic, almost supernaturally healthy young athletes (and mechanics, dancers, hustlers, pool boys, etc.). Physique pictures hinted—obliquely, teasingly—at homo sex but excluded homosexuals. We were outside looking in.

Around this same time, I came across another, even more potent image of naked men together in the pages of one of my father’s old U.S. Camera annuals. George Rodger’s famous 1949 photograph of a triumphant Nuba wrestler being carried upright on another man’s shoulders—the same totemlike image that Leni Riefenstahl said inspired her book The Last of the Nuba—was breathtaking. A real-world Victor and Vanquished, the picture’s body-to-body nudity was all the more stunning because it was so casual, so matter-of-fact. When I realized that the two men were surrounded by a milling crowd of other muscular, naked men, I felt like I’d tumbled through the looking glass. For a profoundly inexperienced fifteen-year-old, the erotic possibilities suggested by Rodger’s photograph were overwhelming. I went back to that image again and again, as if hypnotized, imagining myself in that naked paradise. Clearly, queer is in the eye of the beholder, and mine was wide open and avid. Having grown up with moving images of Elvis, Fabian, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, James Dean, Marlon Brando, Rock Hudson, Paul Newman, and Clint Walker, it would be reductive to say that my erotic imagination was shaped by two photographs. But the still image has always exerted a different sort of power for me, because a picture—in a book, in a magazine, in my hand—could be mine. To have and to hold. As they accumulated, those images began to define my life. The first thing I did in a new dorm room or apartment was tack pictures to the wall, claiming the space with Avedon’s portrait of the teenage Lew Alcindor from Harper’s Bazaar, a Warhol Flowers print, a cover of Body Beautiful, and the sleeve of a Frankie Avalon record. I wasn’t consciously queering the space, but as my rooms filled up with images of men, I realized I was queering the pictures. It didn’t matter who made them or with what intentions. Now that they were mine, they became expressions of my desire, my obsession, my imagination. They might not be gay, but they’d become queer. Context rules.

So what’s the difference? Until it, too, is reclaimed, gay remains the weaker word: fey, wishy-washy, limp-wristed. Screaming instead of shouting. Queer is more transgressive, more audacious, tougher, unsafe, unapologetic. And, it seems to me, more open, more comprehensive. Queer is hungry, insatiable. It doesn’t have a look, a size, a sex. Queer resists boundaries and refuses to be narrowly defined. Which is why, more often than not these days, queer absorbs and appreciates gay, embracing both Cecil Beaton and Peter Hujar, Duane Michals and Wolfgang Tillmans, Wilhelm von Gloeden and Ryan McGinley, Berenice Abbott and Zanele Muholi. And because queer doesn’t care who you’re sleeping with, it takes in Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, and Katy Grannan too. Like the photographs I couldn’t get out of my head, queer is unsettling and exciting and unforgettable. It bites hard and won’t let go.

Vince Aletti reviews photography exhibitions for The New Yorker and photography books for Photograph, Artforum, and W.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 218, “Queer.” Subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.