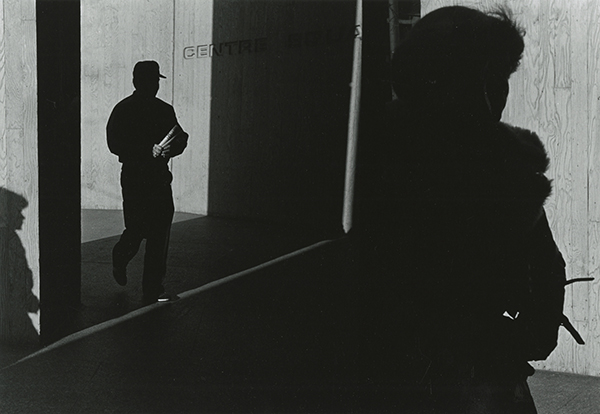

Ray K. Metzker, 63 CM-12, Early Philadelphia, 1963

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Twenty-three empty frames divide the left and right side of Ray K. Metzker’s likeness in 67 DH, Early Philadelphia (1967). Each is numbered and, under every other one, “Kodak Safety Film” or “Kodak Plus X Pan Film” can be read, written upside down. On first glance, the image might appear to be a contact sheet of blown exposures or an empty template. But at either end, silhouetted features—hair, ears, shirt collar—punctuate the emptiness, turning a roll of film into a single image.

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

This contact-sheet-as-self-portrait is on view to the public for the first time among more than fifty photographs surveyed in Ray K. Metzker: Black & Light at Howard Greenberg Gallery. Like 67 DH, which makes a subject out of what is in between by stretching the study across twenty-five shots, the works in Black & Light draw attention to the evolution between various experiments in Metzker’s half-century career. It is in transitions from one formal exploration to the next where the restlessness, frustration, and persistence that set Metzker apart are most clearly on display.

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

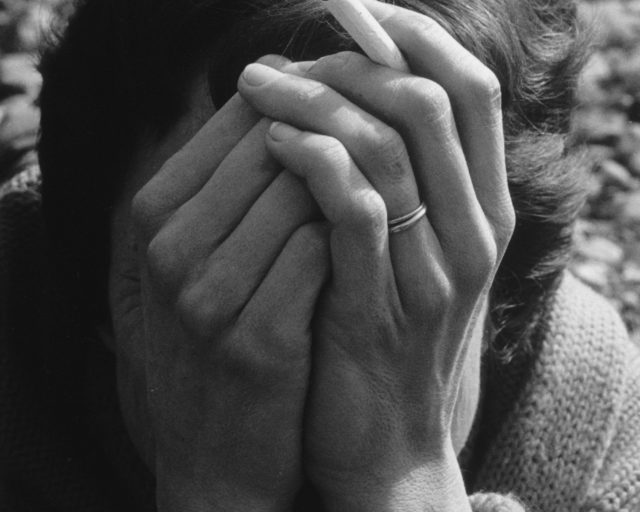

Here street photography hangs near intricate darkroom compositing. Scenes from Chicago, where Metzker studied under Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind at the Institute of Design, mix with others from Philadelphia, where he went on to teach at the College of Art. Faces get close to brushing the camera’s lens; cars, building facades, and interior scenes recede into geometric impressions. A range of action and observation is mounted on the wall here like a score. We can sense Metzker’s interests in theater and music clearly in stark shots of people posted under industrial structures and exchanging passing glances on street corners. In certain images, subjects are found in such dramatic relief that they seem to have been photographed across footlights.

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Black & Light, which is presented on the occasion of Howard Greenberg’s new representation of the photographer’s estate, of course does not provide the context that might be available in a museum retrospective. But the show does present works spanning Metzker’s career, and a look at the rolling innovation that defined it. In two early photographs, a man and a woman stand behind what appear to be thin curtains, some obstruction on the street Metzker has chosen not to avoid. A few years later, he would seek a similar effect in early experiments, holding up film negatives to photograph through and abandoning a dedication to the power of the decisive moment.

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Throughout his career, Metzker identified the boundaries of photographic images so that he could restructure them. It was an inclination that grew out of what Keith F. Davis describes in The Photographs of Ray K. Metzker as an “impatience with the static perspective of the single image,” a frustration with “the essentially realist notion of the photograph as a passive ‘window on the world.’” Metzker might take a photograph and advance the film only partially, muddying the temporal divisions inherent in his camera and film. At Howard Greenberg, a grid of Metzker’s “Pictus Interruptus” images shows him grappling with the too-perfectness of landscapes, lifting things into his frames in order to disturb familiar forms. The objects blot out and mix into architecture in the distance, collapsing space between his vantage and the landscape. Clear indications of people and landscape leave his frames entirely in some later works, where solarized prints, torn and collaged, make rough white paper edges look like photographic highlights.

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

As Davis writes, Metzker’s work encourages us to “think about the adventure of perception in new ways.” His techniques for compositing underscore a tension between the static stipulations of photography and the current of action one might find on the street. Describing the “Pictus Interruptus” work, Metzker explained that he sought disturbances, things that were “foreign in subject but hauntingly right for the picture, the workings of which seem inexplicable, at the very least, a surprise.” Physical aspects of perception were also of interest, and Metzker took to translating them into images. It is an eyeball in rapid motion that charts the world before us, he observed, and holding that energy within the pictures required reaching for and often developing new frameworks.

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

During different phases of his work, Metzker described photography both as a vacuum cleaner used to suck up every detail and as a process like collecting butterflies. The two analogies account for time in very different ways, and we can find a shifting relationship with the delicacy and voraciousness of photography in Black & Light. Formal approaches are adjusted like a watch because, as Metzker explained, photography was for him a way of examining the world by reaching out, touching, and then transforming meaning. “What catches my attention and leads me to trip the shutter,” he once said, “is the first step in a process that may or may not lead to anything that quickens the heart.” The individual works often do. And an opportunity to chart the many directions in which Metzker reached provides a delight of its own.

Ray K. Metzker: Black & Light is on view at Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, through March 2, 2019.