The Humanist Visions of Santu Mofokeng

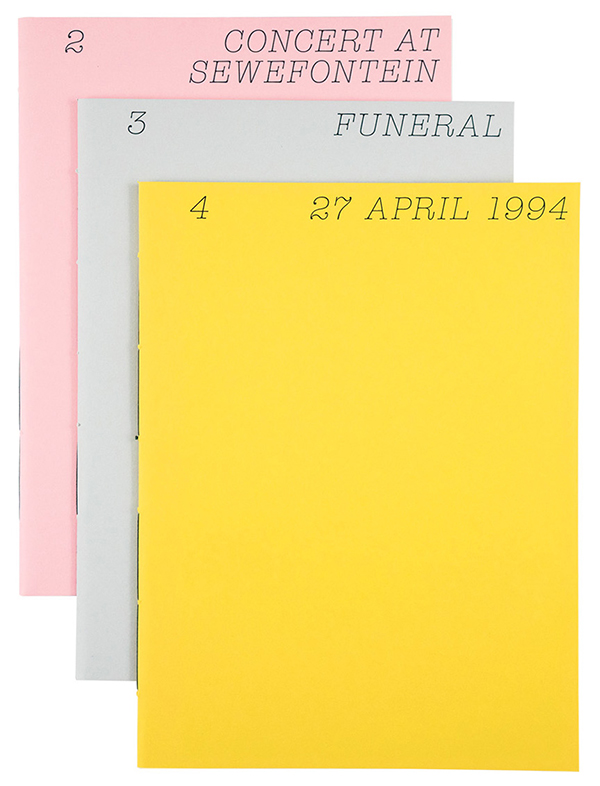

Santu Mofokeng, Stories: 2–4, Concert at Sewefontein—Funeral—27 April 1994

Steidl. Göttingen, Germany, 2016

Why is it that the funereal—the specter of death and dying—still clings to black experience in South Africa? Why is its photographic record still caught in these pathological optics? For all the talk in South Africa of transfiguration and transformation, a psychic shift from death to life, liberation remains in abeyance. Hopelessness continues to conspire against hope, injustice against justice. The photographic record of black South African resistance to oppression has largely been shaped by this paradox, and that includes the images that Santu Mofokeng has relayed to us since the beginnings of his career as a photojournalist.

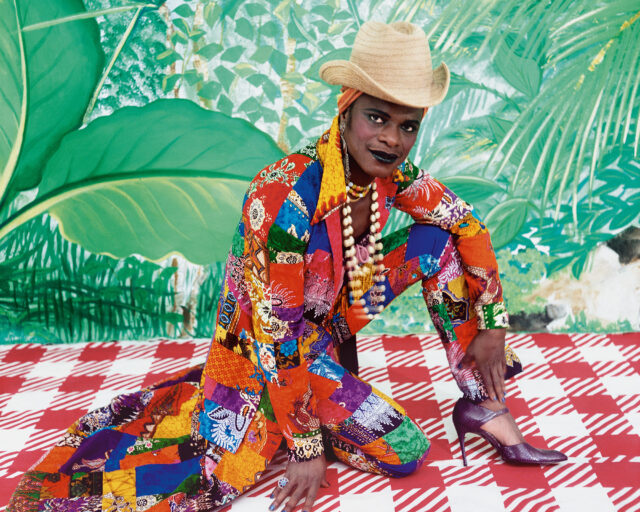

A street photographer who turned photojournalist in the 1980s, Mofokeng, like many others, devoted himself to recording the struggle against apartheid. But his images are never overdetermined by a political agenda: while many other photographers have captured the spectacle of protest, Mofokeng has captured the more subtle sublimity of the body in pain, or the body transfigured—by political belief, by faith. He is widely celebrated as the spiritual painter of South Africa’s tormented body politic, and his uniqueness lies in his ability to capture a subject’s aura, their life hidden from view. In Stories, his multivolume, multiyear book series—the latest installment of which is titled Stories 2–4 (2016)—each individual book is devoted to a singular photo-essay. Through this, the stories of lives hidden or commonly subtracted are elevated and restored to a greater dignity, beauty, and grace.

Santu Mofokeng, Stories: 2–4, Concert at Sewefontein—Funeral—27 April 1994

Steidl. Göttingen, Germany, 2016

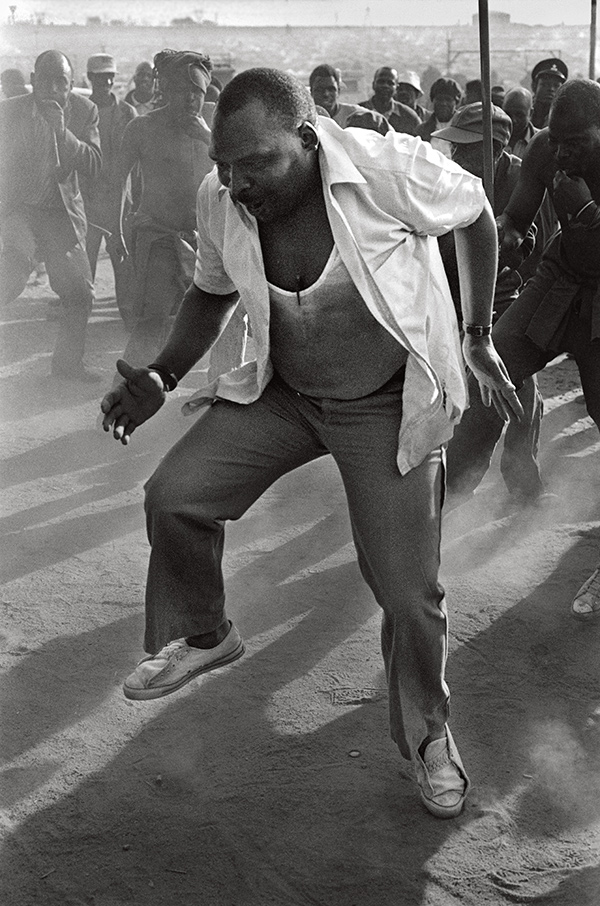

Each of the three volumes of black-and-white images in Stories 2–4 is thin and almost improvisational in feel, but printed with great care using lavish five colors on uncoated paper. The photo-essays comprise three gatherings in or near a South African township called Bloemhof, from the late 1980s to the early ’90s: a concert at Sewefontein; a burial; and a record of South Africa’s first democratic election, on April 27, 1994. These stories are about a collective imaginary. In a photograph from the concert, we see young men together in a line, their bodies thrumming to a beat, faces joyous. But seeing this grouping, we also remember other human chains—those of serfdom. Music, while transfigurative, is also reminiscent of human suffering. This, after all, was the origin of the blues. So while Mofokeng’s photographs are irrevocably tied to the perversities of South African history—inequality, indentureship, and psychic and physical brutalization—they’re also a challenge to global serfdom and ongoing racial inequality, in search of what Paul Gilroy has termed a “planetary humanism.”

The most potent image from these three stories is of a funeral gathering: the grieving and penitent all have their backs turned to the camera—except for one man who is bent, crumpled, drawn to the earth instead of the sky. Upon first seeing this image, I was reminded of Gustave Courbet’s painting A Burial at Ornans (1849–50); there, too, we see a gathering with a central bowed figure. The marked difference, however, is the neatly edged black hole readied for the dead in the fore- ground of Courbet’s painting. No such hole is visible in Mofokeng’s photograph, but it still feels gnawingly there; it is the grave’s absent presence that is embodied in the bent, grieving man. It is the void of which Frantz Fanon unceasingly reminded us—the indistinction which nullified black experience, emptying it and leaving little room for the imagination, for hope.

Santu Mofokeng, Untitled, from the series Pedi Dancers, ca. 1989

© the artist and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

For Fanon, colonization bound up the black experience with its own extinction; its sense of itself would always be tainted, compromised, emptied. It is this dark intuition that shapes Mofokeng’s image of grief. But it is also present in the photograph of the men at the concert—and, in retrospect, we know betrayal also resided at the very heart of a national hope, the subject of the third volume in this set: the country’s first democratic election. Here, Mofokeng gives us an empty street with a placard that reads “The Power to Fight Black,” reinforcing the bitter irony that has dogged hope and compromised black experience in South Africa since 1994.

To Mofokeng’s great credit, however, his visual record refuses to err on the side of hopelessness and despair. Rather, as Monna Mokoena, the director of Johannesburg’s Gallery MOMO, notes, “Santu’s great secret is that he is a poet who uses the camera to tease out of life its deepest meanings.” Mofokeng has never been seduced by the didacticism of reportage. Reflecting on his own photographic take on South Africa’s first democratic election, Mofokeng speaks of “an uneasy sense of euphoria . . . a combination of anticipation and dread, excitement and anxiety.” It is this twist—this glitch, this ghosting—of a profound psychic unsettlement that gives his deceptive record of everyday life in South Africa its enduring potency.