The Lyrical South of Shane Lavalette

Shane Lavalette, Domonique at Sunset, 2010

Courtesy the artist

Barons and earls traveled the world after gold and rubber and souls. They built big building wings and echoey halls, which they filled with curiosities: animal skins, sacred relics, and paintings of their armies’ exploits. The houses became museums. And in most cases, they still are. Walk through those labyrinths of gilt-framed canvases and you see occurrences. Things happen. Important things. A dove flies into a virgin’s bedroom window and she knows she’s been impregnated by God. Sailors cling to life and succumb to death on a ramshackle raft made from the mast of a wrecked French frigate. A severe wealthy man fans his finery. That was what painting was for: to yell “Echo!” from the heights of power, myth, and experience and let it ring in our ears down in the fancy rooms below.

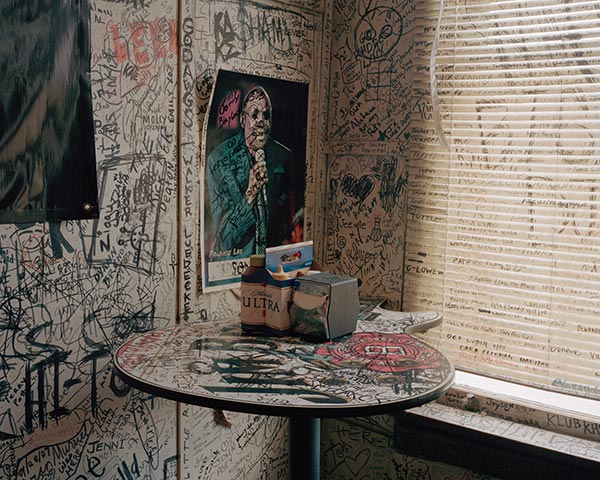

Shane Lavalette, Ground Zero, 2010

Courtesy the artist

Along came photography, and out went the assumption that a work of art had to describe the apexes of experience. The camera is uncaring and undiscriminating. It likes all things (excepting the darkness) equally. The camera doesn’t care whether the man in front of it is a royal or a rube, or if that man is entirely inside the picture’s frame. It is fixed in one instant, from one vantage point, limited to places one human being can actually go while carrying equipment. It is not good at describing the scope of an important battle or sacred revelation, as any one photograph is always a diminishment of a great, epic event: one mouth’s utterance, rather than a heavenly choir. The camera didn’t care for history, mythology, religion, but its interpretation of painting’s lesser genres—still lifes, portraits, landscapes, folks in the fields—was not a diminishment. The camera raised those subjects up. And it did it over and over, with total devotion.

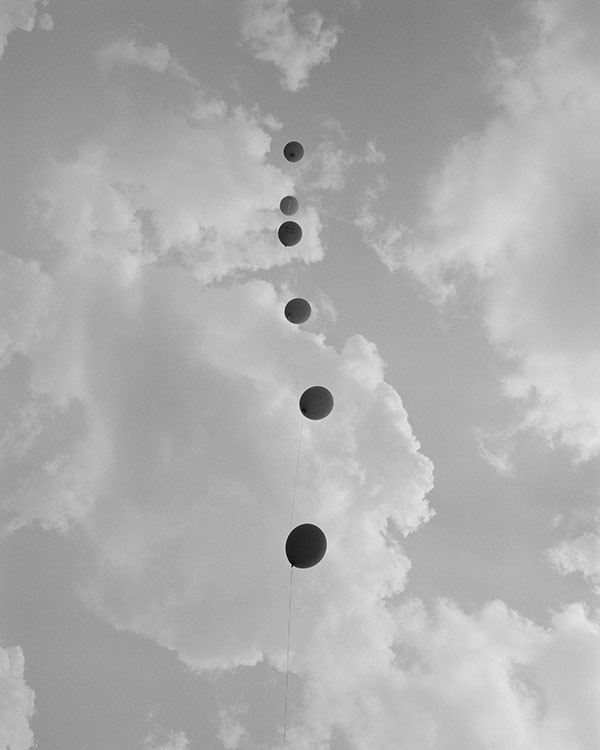

Shane Lavalette, Ready to Roll, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Shane Lavalette is the latest inheritor of photography’s devotion to the lyric potential of the barely occurring. A northerner, commissioned by a great southern museum, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta (with a big new wing of its own), to make a project about the South, Lavalette took as his point of entry the vernacular music of the region. It makes sense. Mark Twain was so moved by the sounds of southern voices he wrote in Life on the Mississippi that “A Southerner talks music,” and the oral is the South’s profoundest point of access. American music comes from the South. Blues, jazz, country, rock ’n’ roll, you know the story. From Stephen Foster to Sly Stone, the South is our musical source and subject.

Shane Lavalette, Ashley at Ben Burton, 2010

Courtesy the artist

And yet a photography project about music sounds like an opera about Helen Keller. The camera, being so single-mindedly visual, is an illogical tool to address music. Lavalette smartly decided not to make a documentary about musicians. He instead scoured the landscape looking for the feeling coming from the music. By avoiding the sanctioned, probing tropes of ethnomusicologists and photojournalists, this young northern artist avoided the conundrum Ma Rainey is supposed to have described: “White folks hear the blues come out, but they don’t know how it got there.”

Shane Lavalette, Binoculars, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Lavalette digs roots instead of picking flowers. He hunts for analogies, hints, circumlocutions. He is not preparing the epic history painting of Southern music; he is finding cunning, lyric fragments of an oral tradition in the visual world and letting them rattle together in his carrying case. There is smoke in the grass, but no fire. Skies only hint at tornadoes. A fence finds itself in fragments. The girls are pretty, the boys are rogues, but the photographer doesn’t fall for feints or flirtations. A tiny toy church sits mysteriously in a field, reminding us of Flannery O’Connor: “I think it is safe to say that while the South is hardly Christ-centered, it is most certainly Christ-haunted.”

Shane Lavalette, Church, 2011

Courtesy the artist

This is a project about a project. Lavalette is accruing meaning about southern music by eschewing information. He moves through those “minor genres”—portraits, landscapes, agricultural scenes, still lives—content to let the project as a whole gather significances along the way rather than laying out a thesis and filling in bullet points. The pictures in Lee Friedlander’s Jazz People of New Orleans are about music not because they have musicians in them, but because they are formally polyrhythmic and alive. Shane Lavalette’s pictures are visually straightforward, obsessively clear, and devoted to the metaphysical idea that direct observation can be beamed through a lens to a viewer. They are quiet pictures that build to a boisterous whole. They speak from the endlessly renewed place of the photographic expeditioner who loves the world and knows it’s a well that never runs dry.

Shane Lavalette’s most recent book, One Sun, One Shadow, is self-published.