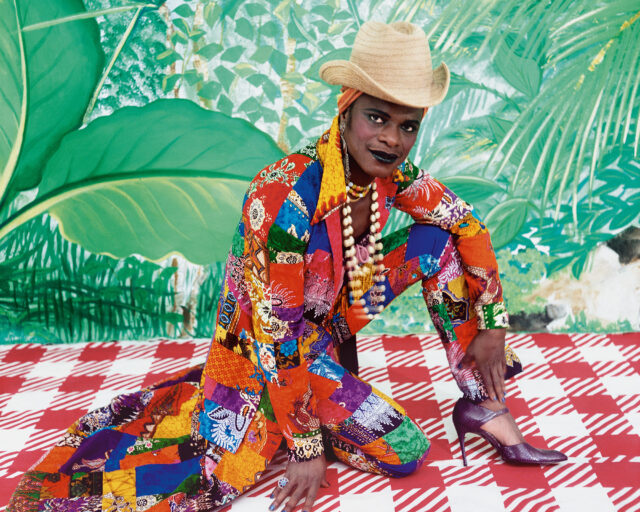

Mikhael Subotzky, Boat 2, 2008

Mikhael Subotzky came to prominence in the mid-2000s with large color photographs and monographs that investigated themes of incarceration and punishment in postapartheid South Africa. From scenes in the Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison outside of Cape Town, collected in the series Die Vier Hoeke (2004–5), and in a frontier town prison in Beaufort West (2006–8), Subotzky produced highly-polished, arresting portraits of people and places bearing the legacy of structural violence. A collaborative project on the Ponte Tower—the “hijacked” Johannesburg skyscraper at the center of Ponte City (2008–10)—considered architecture, segregation, and social identity in the urban landscape.

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

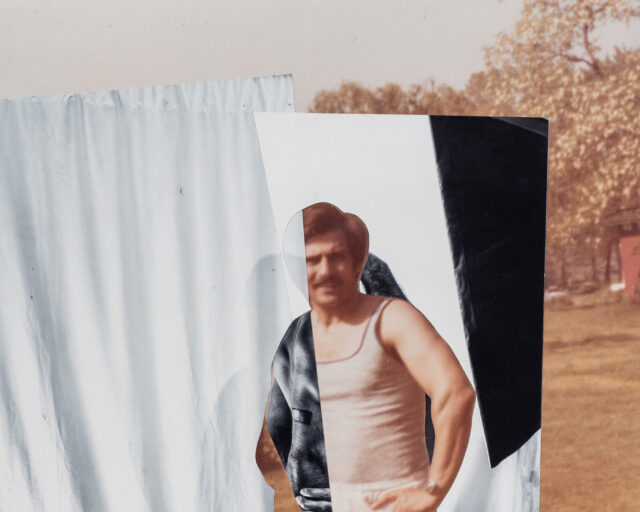

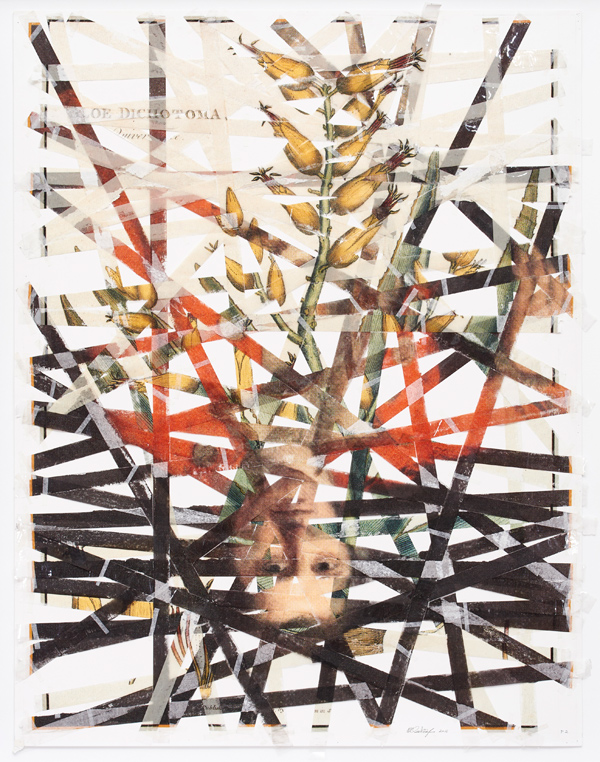

In 2012, with his turn to filmmaking, Subotzky’s practice shifted markedly to more overt considerations of the power of vision itself. His ongoing series of what he calls Sticky-tape Transfers began in 2014 when Subotzky used adhesive to literally prize apart the typically window-like surface of his photographs. Twenty-nine of those collaged transfer images were exhibited earlier this year at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg. But at the center of the exhibition was the three-channel feature WYE (2016), on which Subotzky collaborated with the legendary cinematographer Jörg Schmidt-Reitwein, perhaps best known for his work with German auteur Werner Herzog.

WYE, which was commissioned in 2016 by the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation in Sydney, is named for a river in the western U.K., immortalized by Wordsworth in the nineteenth century. Over the course of forty-eight minutes, WYE draws together three seemingly discrete narratives by centering on a single coastline in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, where the lighthouse keeper Hare spends his days writing and sounding for metal on the beach. Hare’s section of WYE depicts the discovery—with the help of recurring Subotzky collaborator Hermanus—of a buried chest, left behind by the British settler Lethbridge in 1820. Hare’s uneasy encounter prompts him to write to a woman who has left South Africa for Australia, which is analyzed by an archivist of the future, Feio, who provides voice-over narration. Deftly interweaving the stories of Hare, Lethbridge, and Feio, Subotzky produces a timely and compelling account of the British colonial legacy, and its reverberation in a country still making its uneasy transition to freedom.

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Ian Bourland: WYE is a big jump in genre for you. You made a film in 2012, Moses and Griffiths, but that was more of a non-fiction project. Why was film the medium for this particular project?

Mikhael Subotzky: In the case of both my films—Moses and Griffiths and WYE—the choice of medium just seemed to make sense in relation to what interested me about the subjects. Moses and Griffiths deals with overlapping narratives that seemed better suited to moving images and recorded sound, while with WYE, it felt necessary to write fictional characters to really get inside the colonial mindsets of the past, present, and future.

Bourland: In much of your work, you use acute metaphors of precision and vision that you often also undermine. It seems the “Feio” section of WYE reveals all these blind spots.

Subotzky: Totally. When I was at UCT [University of Cape Town], both my girlfriend at the time and my best friend were studying anthropology. I think I learned a huge amount from what they were reading and the discussions around representational responsibility. At the same time, I felt that the degree to which anthropologists get submerged in theory and react to anthropology’s own very fraught history really shut them down. Feio is a “psycho-anthropologist” of the future whose manner expresses the arrogance of progress, of being freed from bodily needs. And yet the experience of embodiment through the “deep enactment” seduces Feio to some extent. I’ve almost exaggerated the blind spots you mention to undermine this arrogance of progress, which is postulated as a colonialist gaze of the future.

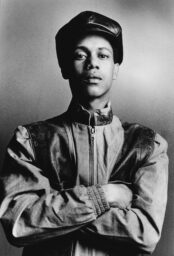

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: There is a moment in WYE where the Hare character is reading an antique letter by a white settler and is embarrassed to be reading it in front of Hermanus, who is black. Is that a reflection of a feeling you had about your work?

Subotzky: I think less in relation to my work but more in relation to being a white South African man. With this project, I wanted to take on white masculinity and collapse or explode it from within the mindset of these three protagonists. I was very much trying to engage with my own sense of shame and guilt in relation to the history of white masculinity, particularly in South Africa.

Bourland: Is the relationship between Hare on the beach and Hermanus indicative of your actual encounters with Hermanus when you were younger? That ambivalence struck me as a sort of typical South African or even white American encounter.

Subotzky: That’s exactly what I was trying to write in that scene. I did it as an exaggeration of that kind of experience; Hare is really like a typical white South African. Hermanus walking up to him is an exaggerated dramatization of how I actually met the real Hermanus. He was behind a wall that he was bricklaying on a building site. He asked me, “What are you doing?” That was the first thing he said to me. And he was genuinely interested in what I was doing with a camera, and then he asked me to take his photograph, and that’s how we got to know each other. In the film, Hare assumes that Hermanus is begging, but he is actually just interested in what Hare is doing—metal-detecting on the beach. Then Hare feels this kind of guilt at the assumption and overcompensates, but he’s very patronizing in explaining what he is doing with the metal detector.

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: There’s an irony, then, with the “Lethbridge” section, which suggests that the British colonialist may be an irrational figure.

Subotzky: Absolutely. Lethbridge comes with that very particular early-nineteenth-century combination of the occult and the scientific. The title WYE alludes to the Romantic era—especially in painting and poetry—and the Romantic way of looking at the landscape, and also to Wordsworth’s poem “Tintern Abbey,” which was written on the River Wye and became a foundational text of the Romantic gaze. With Lethbridge, it was a real balancing act to write him in a way that he wasn’t just a bad person—so you could kind of identify with him—but also to reveal the arrogance that the land was there for him to study and do experiments on, and then he goes mad.

Bourland: The film is set in three time periods on one beach in Port Elizabeth. Is the Eastern Cape especially significant?

Subotzky: I grew up in Cape Town and moved to Johannesburg in 2008 because I hate how pervasive the physical structures of apartheid still are in Cape Town, the sense of separation, everyone pretending they are in the south of France. Grahamstown—the town where I shot Moses and Griffiths which is in the Eastern Cape—is even worse. It’s literally this figure of eight shape with these two bowls: the British colonial town is in one bowl and the black township is in another. WYE really emerged out of Moses and Griffiths. I wanted to link three temporalities and geographies to the gaze of the white colonial body, so using the backdrop of the Eastern Cape and the 1820 Settlers made sense. The beach that 1820s Settlers landed on was literally the beach in Port Elizabeth where we shot.

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: The 1820s Settlers being the people sent down from England to populate South Africa.

Subotzky: Exactly. And more specifically to populate the particular part of South Africa where there was a lot of conflict between the Afrikaners and the Xhosa. The colonial government was struggling to police that frontier and they really fucked everyone over, including their own countrymen. They brought working-class people over from England to act as a buffer with the promise of land, but it turned out to be poor farming land given to people who weren’t skilled farmers. But the fictional Lethbridge, an 1820 Settler, never makes it off the beach onto the land proper; instead, he goes mad in the liminal zone between the sea and the landscape.

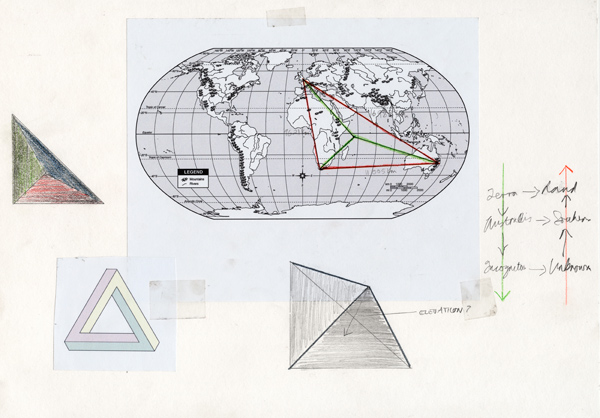

Bourland: WYE connects this history to similar histories around the Indian Ocean and specifically in Australia.

Subotzky: In 2016 I was invited to go to Australia by the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation in Sydney. In going there, I read The Fatal Shore (1986) by Robert Hughes, an exhaustive, amazing history of the Australian penal colony. I was deeply struck by one of the early chapters called the “Geographic Unconscious,” which describes how the British had to imagine the Australian landscape as upside down, inhospitable, and unfriendly in order to politically justify the use of Australia as a dumping ground for criminals. This “otherization” of the landscape contrasted so strongly with my experience of the way that contemporary white middle-class South Africans idealize the Australian landscape as being “just the same” as ours here, but without all of the “problems.” So it was really that part that got me thinking about the complete turning around of that projection onto the Australian landscape over a couple of hundred years. I literally saw that in my mind on the map as two sides of the triangle. And I drew a line between England and Australia, South Africa, and Australia, and then started thinking about the third side of that triangle, which was the English projections onto the South African landscape.

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: WYE follows your recent project Ponte City (2008–14), created with Patrick Waterhouse, which tracks the iconic Johannesburg apartment tower of the same name through photography, installations, and archives. Since you began work on Ponte nearly a decade ago, how do you feel about the direction Johannesburg is moving today?

Subotzky: This is an important moment in our history because the political corruption of our liberation movement is combining with the student protests and a stagnant economy to create a lot of conflict. Issues are coming up that really need to be addressed—how little has changed economically for the majority of people, the pervasive racial problems, and the depth to which colonial thinking has seeped its way into all of our institutions. Some people are very, very pessimistic today. But Johannesburg is amazing. Between my studio in Maboneng and Ponte, which is only a couple of kilometers away, they’re about to open this beautiful new residential building that David Adjaye has designed. There is so much going on that is dynamic and engaged.

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: Have you heard anything in South Africa about the controversy at the Whitney Museum over the inclusion of Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till in the current biennial? Many South African artists, such as yourself and Pieter Hugo, have been thinking for a long time about this question of who can represent whom, who can represent scenes that might actually cause trauma.

Subotzky: Well, I have totally been thinking about it. And those kinds of ideas have been in my thoughts throughout my career. But very, very consciously, I mean, for part of Retinal Shift (2012), I did a wall of a hundred photographs which was called I was looking back; they are all taken from my archive from the eight years of working before that. One of them was a photograph of a prisoner who had been burned to death in a cell. His mother had actually asked me to take that photograph, and even though she was grateful to me for taking it, and it felt very important to her, I felt very uncomfortable. I was literally haunted by the photograph, but I also felt very uncomfortable in terms of the kind of issues that came up around that Dana Schutz painting. I had this instinct that I wanted to smash the photograph; I don’t know where it came from.

In retrospect, it was about writing my own feelings into that work. It had its function in documentary terms, but it also had its function in personal terms for the mother who was so grateful for me giving it to her. But my own trauma of seeing this violently burnt body was written out of that narrative, so I smashed it. And in smashing it—I mounted glass in front of it and smashed the glass—it felt terrifying and felt like I might be reenacting the trauma and violence that was done to that man. But I realized what I was doing in smashing it was covering up the representation that in many ways I wished hadn’t made and kind of “re-shrouding” of that body.

There’s a battle between being sensitive to all the issues of representation, but also wanting to be brave enough to make representations and think about the positive functions that representations can make. And for me, living in South Africa, it would be ridiculous to, for instance, only photograph white people because white people are less than ten percent of the population.

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Bourland: In describing your process, there is at times a sense of anxiety or ambivalence that comes out, a masochism towards the work. As a white artist now, is all that there is left to deal with guilt or shame?

Subotzky: We have to engage as citizens. So many white people are on social media commenting and writing in columns and participating in “virtual politics,” but we haven’t delved nearly enough as white people into how pervasive our privilege is. And how we are quite desperate to hang onto it. I think it’s more about shame than guilt. Guilt is very particular; there is nothing one can really do about guilt. Shame can be understood. It’s a starting point in relation to where we are now with the political climate and these student movements. It is something that has to be done before we can move onto actually thinking about our broader place in society.

WYE was on view at the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, from March 2–April 2, 2017.