The Image World Is Flat: Penelope Umbrico in conversation with Virginia Rutledge

In 2008 Patrick Cariou brought a copyright infringement suit against Richard Prince. Prince had used images of Rastafarians photographed by Cariou and published in a photobook to create a series of collage paintings. At the trial level, Prince’s use of Cariou’s images was ruled infringing, and the case is now on appeal. Debates around appropriation raise a number of questions regarding creative freedom, fair use, and transformative versus derivative borrowing. However, a less examined aspect of legal cases involving art is the role played by visual evidence. Here artist Penelope Umbrico, known for her work with images sourced from various print and online contexts, speaks with art historian and intellectual-property lawyer Virginia Rutledge about the use of reproductions in our increasingly flattened image world. —The Editors

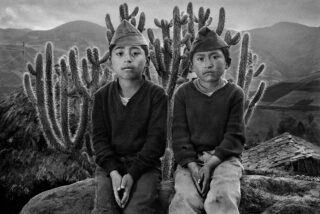

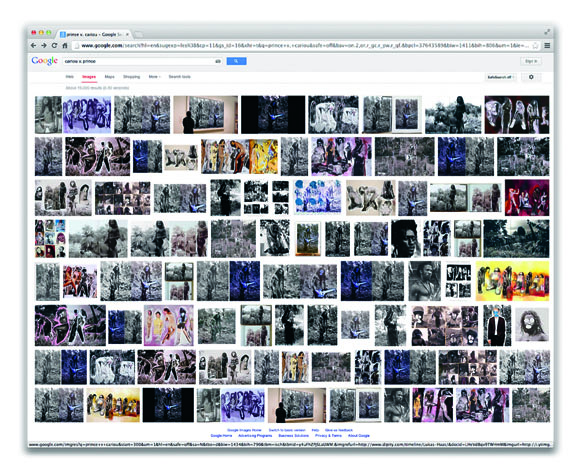

Virginia Rutgledge and Penelope Umbrico, cariou v. prince/Google Image Search on 11/07/2012, 2012; digital collage of the first eighty-five images of photographs and paintings by Patrick Cariou and Richard Prince found on Google Images during a single “cariou v.prince” search.

Penelope Umbrico: I’d like to start with something you said recently on a panel about the Cariou v. Prince case. You mentioned that judges don’t always see the art involved in litigation about copyright, but may only be looking at reproductions. I tried to imagine both Cariou’s book-sized black-and-white photographs and Prince’s giant color paintings reduced to standard 8.5-by-11-inch photocopies. It strikes me as absurd that people who aren’t familiar with the actual works are asked to compare reproductions in order to make a judgment about them.

Virginia Rutledge: It is absurd, but not uncommon, for courts to consider images of art rather than the art it self. Certainly there can be logistical challenges in making a direct examination of disputed artworks, if we’re talking about bringing enormous paintings like Prince’s into court or arranging judicial field trips. But the greater challenge is to see what is at stake if the only reference point is a set of reproductions! Maybe the concept of hearsay is useful here. Basically, hearsay is a statement made by someone out of court, so there is no witness to directly question or test for credibility or veracity. There are exceptions, but generally hearsay isn’t admissible as evidence of the truth of what the statement asserts. Obviously we can push this analogy much too far, but reproductions of art are largely hearsay—they shouldn’t be taken as evidence of the “truth” of the artistic statement.

PU: Relying on reproductions as evidence seems particularly problematic in this case, since the finding of “transformative use” is so important in determining whether an appropriation of a copyrighted image is fair. How can a court understand where artistic transformation occurs if the documentation moves through generations of degradation entirely beyond the artist’s control? There may be very little space between a photograph and its reproduction in a good print publication. However, an image of a painting in a book is always going to look like a reproduction of a painting—we are obviously looking at one medium seen through another. Seeing a photocopy of a photograph side-by-side with a photocopy of a photograph of a painting really doesn’t give us any sense of what we are supposed to be looking at. Both sides of the evidence actually start to look alike.

VR: That is a very funny and scary observation, not least because the charge of copyright infringement depends on the existence of “substantial similarity” between works, to use the legal term. I have to agree that reproductions can cause serious damage to the understanding of paintings rather more quickly than may occur with some photographs. But perhaps this is just a more insidious problem with respect to photography, and maybe the photobook in particular. Neither Cariou nor Prince is well represented by most of the images of their work that are circulating in the media at the moment. And in Cariou’s case the images are completely severed from the context of the book in which they initially appeared.

PU: Well, yes, and, if this is the argument, then any single image that is excerpted from Cariou’s book is actually transformed by just that decontextualization alone.

VR: That separation from the book context definitely alters my perception of the work, as it would if I saw the images printed and framed as separate objects. This is where vocabulary can be tricky, though. Showing a single image from Cariou’s book does not necessarily “transform” it in the sense that’s relevant for copyright. And with respect to art, it may be entirely relevant who does the decontextualizing and why. As we’re talking to some degree about the artists’ intentions, it’s important that we credit how much the art world makes of how an image is presented and encountered. That understanding is central in the critical discourse about documentary photography, and it also underpins our appreciation of the meaning of artistic strategies involving appropriation of images, in all their great variety. Is it controversial to suggest that people who spend more time in studios, galleries, and museums are probably going to be more attuned to meanings produced by shifts in context and better at reading reproductions of art than people who spend less time? What can we reasonably expect of the average judge or juror who may not have the same experience of art, and the same visual expertise?

PU: I began with this idea of the photocopy because I think the distance it represents equates with a lack of visual sensitivity. It points to the assumptions we make based on viewing images through such media of mass distribution.

VR: It’s curious. We all know certain musical scores or motifs, and we hear the musical work across different performances and different technologies of recording. But we are also very aware that the work is being realized at this moment in this way. The role of performance in the perception of “the work” is one of the things that makes music and sound different from the visual arts, and as contemporary art embraces hybrid media we can experience ever more powerfully when and why those differences matter. When we’re looking at still images, however, it seems easier to lose sight of the work if we fail to see the mediation of reproduction. It’s rather alarming to imagine judges comparing reproductions of different works of art and thinking that they are considering impartial evidence, when in fact what is most in evidence is the flattening effect of technologies of reproduction.

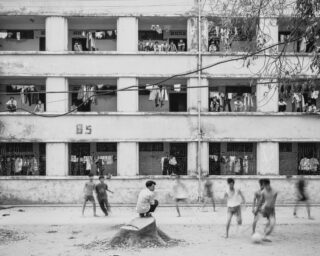

An illustration as published on artinfo.com to accompany the article “Is Prince v. Cariou Already Having a Chilling Effect? Contemporary Artists Speak,” by Julia Halperin, found at http://www.artinfo.com/news/story/758352/is-prince-v-cariou-already-having-a-chilling-effect-contemporary-artists-speak.

PU: So the work itself becomes neutralized and leveled. It’s not unlike what happens to images on the Web—where they have no physicality, place, or specificity. Though the screen itself is clearly a medium through which we see the image, the “object-ness” of the actual works is lost and so they can be moved from one setting to another with ease.

VR: Yes, and without the right caption, so to speak, it is easy to mistake the image. This reminds me that some years ago when art history lectures still involved analog slides, I needed an image of Sherrie Levine’s now-classic After Walker Evans. There was no easy-to-hand reproduction of Levine’s work, so I made my own—by substituting an image of the Evans photograph. Of course neither work is adequately represented by a slide surrogate.

PU: It’s a good example of how invisible the medium is, and therefore how easy it is not to acknowledge its particularity.

VR: Thus the danger of overreliance on reproductions of art in legal cases: it helps dumb down the fair-use analysis to an exercise in mere image recognition. The role of context in shaping meaning is disregarded, and visual connoisseurship is ditched. If the test for copyright infringement is simply “match the image,” the first copyright holder will always win. Fortunately there’s much more to fair use. What matters most is whether new expression or meaning is created. Fundamentally, that is why Cariou v. Prince is so perplexing. It’s easy to spot “Cariou’s” Rastafarians in Prince’s paintings, but even the Prince works that make the least visual changes to Cariou’s imagery clearly make a different artistic statement.

PU: And if the test for infringement is image recognition, then this tests our assumptions about who “authors” the recognizable aspects of the image. Why are they “Cariou’s Rastafarians”? I’m not saying we should contest Cariou’s authorship of his photographs, but if it comes down to the recognizability of his subjects, then shouldn’t we?

VR: It’s an intriguing point, and suggests a huge discussion about “cultural authorship” and some additional legal rules—next time, perhaps! Let’s return to your mention of the Internet as not only a distribution platform for this material, but also as a leveling mechanism. Consumed via the screen, images certainly can be subject to a kind of leveling not unlike what happens when reproductions of art are gathered for a set of legal exhibits.

PU: So, we end up with an example like this image created for an article on the case published by Artinfo.com—a mashup of a relatively small Cariou photograph and a much larger Prince painting, inserted in what appears to be real space. There’s no perceived physical difference, or distance, between the two works. Some people, including myself at one point, have mistaken this manipulated illustration for an installation shot of an actual work of art. And this image is now all over the Web, often with no attribution. Seeing it in the flat sea of other images is confusing.

VR: Absolutely—although no one familiar with Cariou’s photography could think for a moment that this is his work. So thank goodness there’s a credit line for all those who may not happen to be in the know. Well, how very nice of “Flickr and the Artists” to allow their work to be reproduced in this way! Which just proves that context can be everything.

—

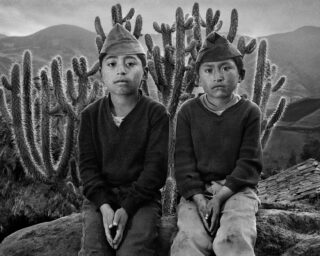

Top image: Virginia Rutledge and Penelope Umbrico, detail from Images and Texts, 2012; digital collage of images and texts, output variable.

Penelope Umbrico is a visual artist based in New York. She currently holds a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship. Penelope Umbrico (photographs) was published by Aperture in 2011.

Virginia Rutledge is an art historian and attorney based in New York. Formerly a curator for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, a litigator at Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP, and vice president and general counsel of Creative Commons, she is now in private practice focusing on intellectual property, contemporary art, and cultural organizations.