The Photographer Who Constantly Transforms

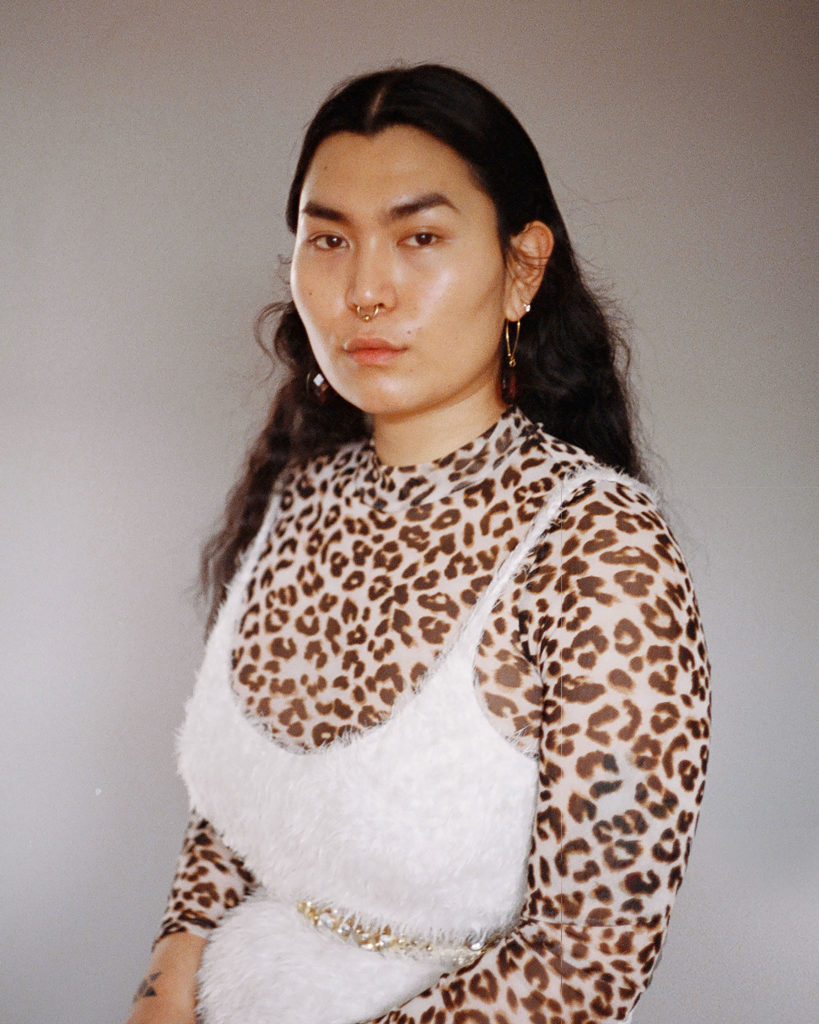

In their portraits in the American West, Evan Benally Atwood builds a vibrant narrative about trans and Native lives.

Evan Benally Atwood, kerry (detail), 2019

When I first tried to reach Evan Benally Atwood, their phone lay buried underneath a foot of new snow blanketing a cross-country skiing trail at Mount Hood. It was almost spring here in Oregon, so maybe, when the snow began to melt, draining out to the Hood River, past my house, down to the Columbia River Gorge, and then out to the Pacific Ocean, Benally Atwood’s phone would reappear.

A snowy mountain trail is the type of place where Benally Atwood feels compelled to take out their 35 mm rangefinder. They make work throughout the American West, often in the high desert of Central Oregon, which reminds them of where they grew up in New Mexico. They often put themself in the frame, wearing things like cowboy hats and other bits of Western wear, paired with sparkling silver heels or a tsiiyéeł, a traditional Diné (Navajo) hair bun. Sometimes, they don’t wear anything. These signifiers of identity frequently come together in unexpected ways.

Benally Atwood identifies as nádleehí, a Diné word that roughly translates to “one who constantly transforms.” They told me they journaled about what the term might mean for them when they first encountered it: “I never claimed the term two-spirit—it wasn’t something I felt inside. For me, nádleehí is that which is always becoming. I feel more masculine and more feminine today than I did when I first wrote in my journal. I feel blessed to be in my body.”

Benally Atwood describes their gender identity as an act of reclamation of Diné ancestral knowledge. “The Diné have five genders, and have had those five genders since before colonization. The gender binary was pushed on us. In a lot of Indigenous cultures, gender is psycho-spiritual rather than physiological,” said Benally Atwood. But they also noted that they weren’t taught these ideas about gender variance when they were growing up, and they don’t see it widely taught now. This process of reclamation is ongoing and embodied in their photographs.

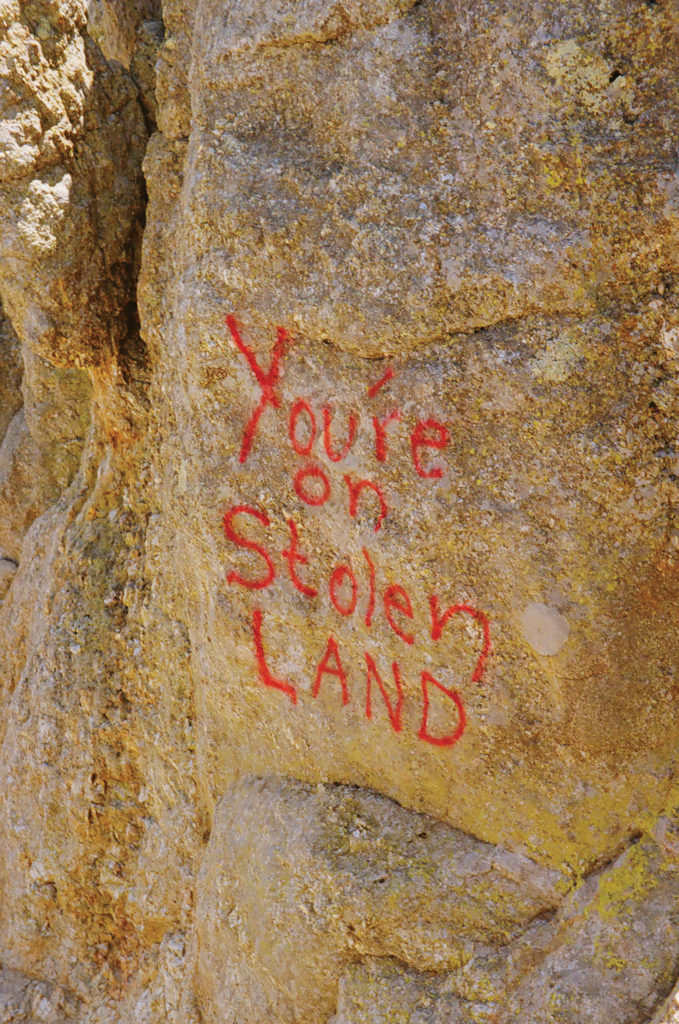

In the beginning of our conversation, Benally Atwood told me they don’t know what they are taking pictures of most of the time. “It’s a mystery . . . in an Indigenous way,” they said. “A lot of Indigenous communities talk about Spirit as the Great Mystery—the creator of all. So I try to honor the mystery of existence. I try to honor the land that I get to be on.”

As Abaki Beck, a Blackfeet and Red River Métis writer focusing on Indigenous feminisms and revitalizing Indigenous knowledge, told me: “Many Native people, myself included, have an intimate relationship to the landscape. It is where our stories come from, where we gather our medicine, practice ceremonies, or connect with loved ones. Evan portrays this relationship to the land in a vividly intimate way, which stands in sharp contrast to typical photographs of Western landscapes as colonial, touristy, or voyeuristic.”

Benally Atwood grew up in Farmington, New Mexico, a border town to the Navajo Nation. They describe the city as “incredibly conservative,” and left when they were eighteen, after graduating high school. They received a degree in business administration from Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, in 2015, and eventually settled on the ancestral lands of the Chinook tribe—Portland, Oregon.

Considering the way Benally Atwood’s work investigates the intersection of queerness and the legacies of colonization, I asked them if they have read Billy-Ray Belcourt’s A History of My Brief Body (2020), a genre-bending collection of essays that explores many of the same themes. “Sort of,” Benally Atwood said. They had it in front of them as we spoke, but still needed to finish it. I read to them aloud from the introduction, which was a nice experience—if you have the chance, I recommend reading a book you like (even a few lines) to a friend over the phone.

“I’m up against decades and perhaps centuries of a literary history that extracted from our declarations of pain evidence of our inability to locate joy at the center of our desire to exist,” Belcourt writes. “With you, I can rally against this parasitic way of reading, this time-worn liberal sensibility. Together we can detonate the glass walls of Canadian habit that entrap us all in compressed forms of subjectivity.”

What Belcourt describes here applies to our reading of Indigenous images in “North America” irrespective of colonial borders. In Benally Atwood’s photographs, joy, and also pleasure, operate in a similar way. They rally against the same stifling liberal sensibility that views Native communities exclusively through the lens of pain, and more often than not, erases them entirely. But finding and documenting joy and the places where it can exist in the wrath of colonization is not easy.

“I think for me, nature is the place to access joy. The problem is that nature in the Pacific Northwest is so white-centered. Many of my friends who are trans feminine, Black, and people of color aren’t as comfortable being outside,” said Benally Atwood. As a result, Benally Atwood makes a point of creating portraits of trans feminine individuals outdoors. “I love being able to document and help them see themselves in a beautiful way. Sometimes, taking photos is literally just about going to a place where you want to feel cute and fun.”

On the surface, this intention could be read as lighthearted, but given the historical context, the stakes remain high. “Usually, the narrative of Indigenous people in the landscape is one that revolves around trauma, which gets told and retold,” said Benally Atwood. “These pictures are about creating a narrative ourselves for ourselves.”

All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.