The Photographers Who Envisioned Queer History and Resistance

An exhibition showcases artists and collectives that built queer image cultures with lasting influence.

Lola Flash, Clit Club Series, ca. 1989–90

Courtesy ART+Positive Archives

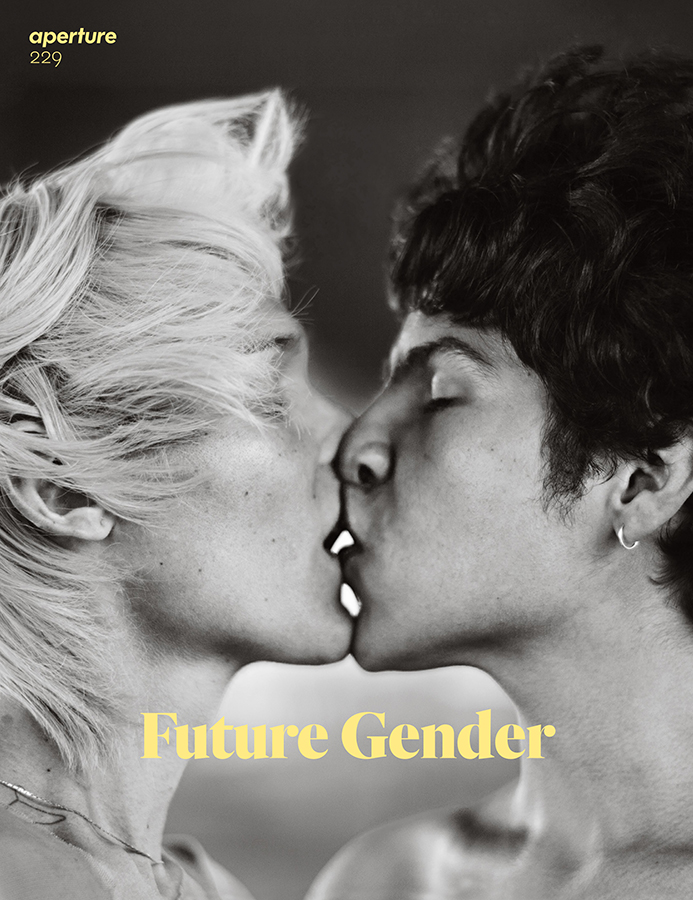

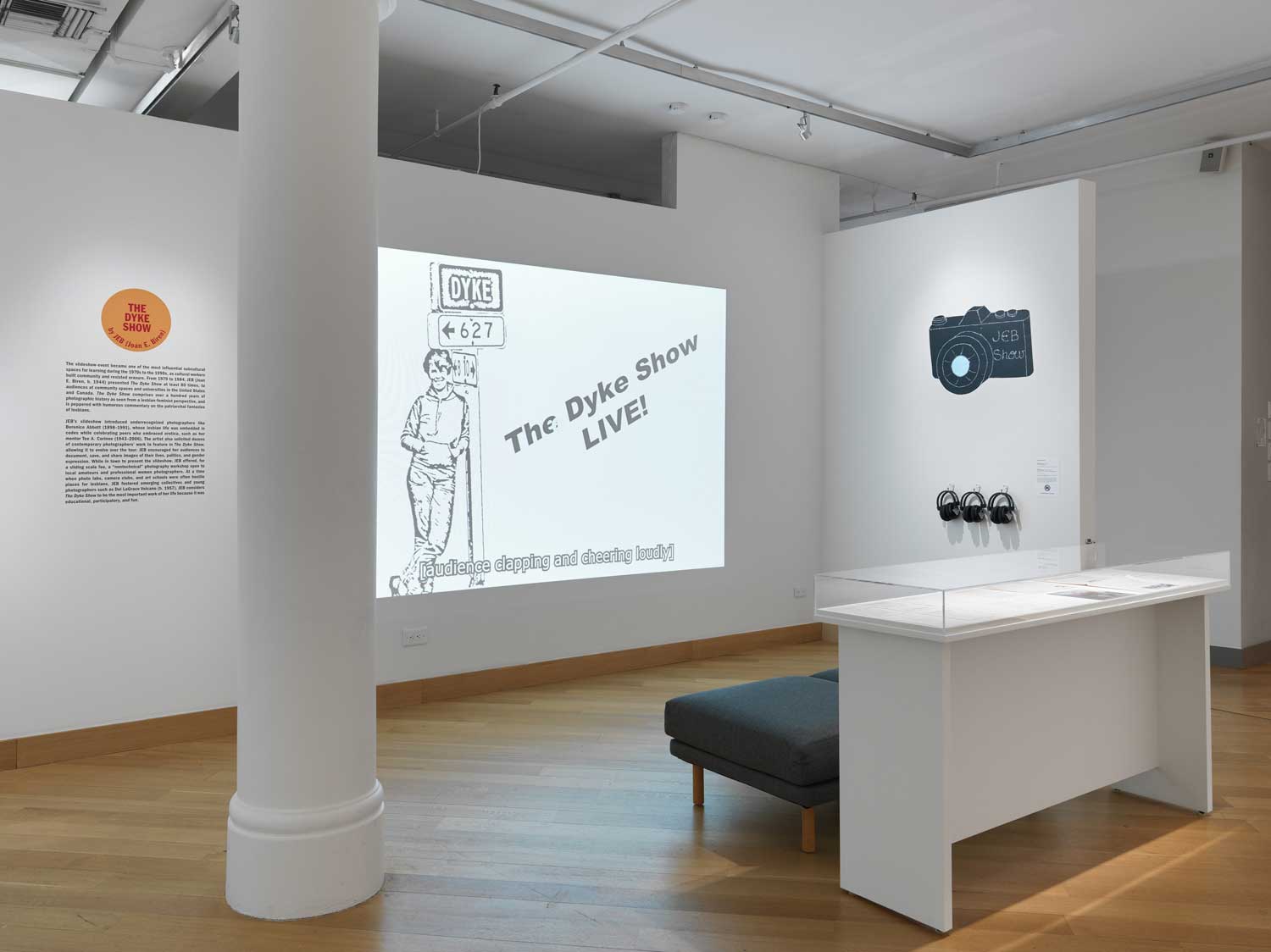

On the evening of February 9, 2023, in a standing-room-only presentation for a raucous audience at the LGBT Center in Manhattan, Joan E. Biren (JEB) did something for the first and last time in thirty-nine years: a live performance of her Lesbian Images in Photography: 1850–the present (1979–1985). The Dyke Show, as it is more popularly called, is a slideshow comprised of hundreds of portraits, documentary images, and erotic photography by artists ranging from Alice Austen to Tee Corinne. Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s, an exhibition curated by Ariel Goldberg and currently on view at the Leslie-Lohman Museum in New York includes a digitized version of The Dyke Show and seeks to carry on the ambition, enthusiasm, and intergenerational through lines of JEB’s work.

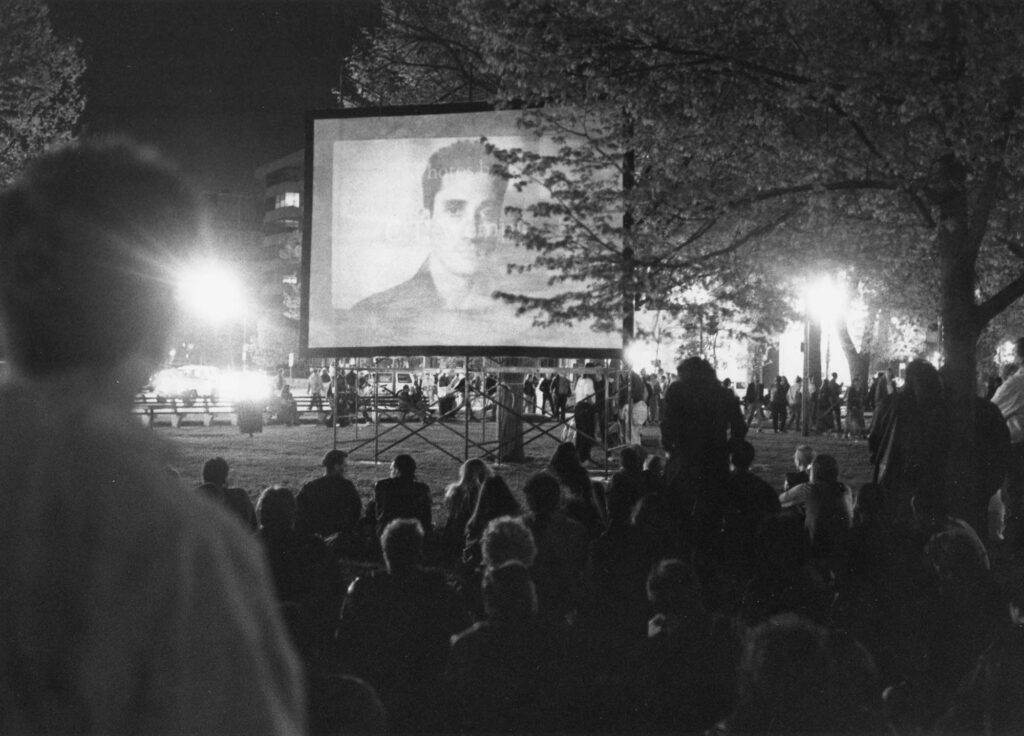

The exhibition is overwhelming—in the best way—in its six distinct but inextricably connected sections. These include photography by Lola Flash alongside ART+ Positive (a small artist collective dedicated to fighting AIDS phobia); documentary images from the vast archive of artist and educator Diana Solís; a selection of images of African American lesbians from the Lesbian Herstory Archives; snapshots, correspondence, and newsletters that showcase sundry trans networks; and Electric Blanket, a slideshow installation of images related to HIV/AIDS, from portraits of dead loved ones to photo essays to protest slogans and statistics.

Images on which to build, which was originally presented at the 2022 FotoFocus Biennial in Cincinnati, showcases artists and collectives that participated in, and ultimately built, robust trans and queer image cultures with lasting influence. The title card for each section looks and feels like a vintage activist button, reminding us that these projects were never only “art for art’s sake.” And neither is this exhibition. Indeed, in form and content, Goldberg’s mission is in keeping with their predecessors’: the work is offered in the spirit of education, inspiration, and interconnection.

I recently spoke with Goldberg, who exudes passion and purpose. “When I started to approach people, my tenor was one of humility,” they told me. “I never thought I was discovering anyone; I was simply bridging the gaps of historical erasure for all those artists and culture workers who have been ignored by incomplete photographic histories.” The result of their gap-filling is a sort of interstellar vastness as moving as it is galvanizing.

Courtesy the artist

Kerry Manders: What was the impetus for this exhibition?

Ariel Goldberg: The fire—fueled by anger and disbelief—really started in 2015 when I was finishing my book The Estrangement Principle about the label “queer art” and asking: what’s my queer lineage in photography?

I knew it had to be deeper than Robert Mapplethorpe and his Hasselblad. I was starting with how modes of representation are contested in queer history, reading Isaac Julien and Kobena Mercer, thinking about Lyle Ashton Harris and others who were pushing back against an elite white gay male history. I wanted to learn about everything that doesn’t assimilate into the commercial fine art world.

The fire was also ignited when I read Sophie Hackett’s article on The Dyke Show by JEB [Joan E. Biren] in the “Queer” 2015 issue of Aperture. That gave me a concrete example of what we could find if only we looked.

Manders: Your mission was to recover and re-present those artists.

Goldberg: I started this research in part because I wanted to experience the slideshows that I was told I can’t see anymore because they were live events. You can reconstruct historical multimedia projects like The Dyke Show if you are devoted to the long process and move at the speed of trust with the people who made them.

Courtesy the artist

Manders: Can you give us a snapshot of this moment in time on which your exhibition focuses? How do you differentiate it from what came before?

Goldberg: The late ’70s through the late ’90s is a very important moment in trans and queer history because that was when people were coming out and taking that risk in perpetuity: they were not going back in the closet. Right before this, visual records of trans and queer life most often belonged to the state—like arrest records—or were tabloid-y, sensationalized news stories of gender “discovery.” There were criminalizing narratives, or even outright destruction—families destroying personal archives of their queer relatives and even people destroying their own archives for fear of discovery. Even Diane Arbus’s photograph of Stormé DeLarverie was too controversial for Harper’s Bazaar to publish in 1961.

Manders: Where and how did you find these artists? Can you pull back the curtains on the “making of” this exhibition?

Goldberg: It’s multifaceted—there’s no template. My methods depend on the person I’m researching. I do the maximum amount of research I can before engaging in dialogue with an artist or archivist.

The artist Nicole Marroquin, whom I met at a Magnum Foundation event, introduced me to Diana Solís. Ever since, I leave each conversation with Diana—and the many artists and scholars working with them—with more names of people and events to look up, more books and articles to read. I remember the first time I visited Chicago, Nicole said I must read this book Chicanas Movidas, and has since shared articles in English on the Encuentro Feminista Latinoamericana y del Caribe. I still have a lot of learning to do about Chicago social movement history, Chicana, Mexicana histories of the Midwest, and Latin American feminist history if I’m to even fathom Solís’s work.

I apply to get travel funds that are available through archives to go to personal papers. I basically riffle through boxes and boxes of stuff. I try to zoom out and understand who was supporting the photographers’ work. Especially when I was just beginning in JEB’s papers, I started to see repeated names like Tee Corinne and Morgan Gwenwald, and patterns of relationships.

Courtesy the Artist

Manders: That’s lovely. You built this exhibition via a network of relationships you found in the archives, which you then translate in your curatorial choices. Interconnection and overlap are key elements of the show.

Goldberg: Yes! When I was working with Diana Solís on the edit of their photographs, I remember getting excited when I saw, in the background of a photograph taken at Mujeres Latinas en Acción, matted photographs on the wall behind the table where a group of women were having a meeting. That group included Diana’s mother, their friend Diane Ávila, and her mother, too. When I asked whose photos were on the wall, Solís responded it was their own work and likely their students’ work from the photography class they were teaching at Mujeres in the late 1970s.

The late ’70s through the late ’90s is a very important moment in trans and queer history because that was when people were coming out and taking that risk in perpetuity: they were not going back in the closet.

This scene is what I am hoping to achieve with the exhibition broadly: creating a space for people to gather and make connections about photography and art’s critical role in organizing across generations. At the openings in Cincinnati and New York, artists and archivists from different cities were getting to meet and appreciate each other through the varied contexts of each other’s work.

The goal was not only about finding material, but also about meeting and connecting people who were not already acquainted. Personally, the ongoing power of this work is the relationships and mentorships I’ve been lucky to cultivate through this process.

Manders: That makes me think of one of the various resonances of the exhibition title—images on which to build relationships. This exhibition seems to be as much about community as it is about art.

Goldberg: Aldo Hernández, one of the organizers of ART+ Positive, reminded me that their work was about communities and collectivities, not about individuals and careers. It was about organizing and doing as much as you could with what little you had. He once said to me, “Oh, we were foam core queens!” And I thought, That kind of sums it up, getting work out there in the ways that were most affordable and easiest to schlep around.

One of my design challenges was to honor the Lesbian Herstory Archives foam core exhibition boards alongside framed archival ink-jet prints. I wanted to show that these practical materials traveled. They’ve been to student centers and volunteer-run archives. That ding on the corner of the foam core board—that wear and tear—is filled with the love of the previous audiences receiving the work.

Manders: What have you learned in the process of curating this exhibition? What are some crucial takeaways?

Goldberg: The first, most beautiful lesson is that organizing as image makers takes so many different forms.

On the one hand, I’m looking back. I’m doing all this inspiring time travel and celebrating the ways in which our predecessors came together and solved problems. AIDS activists learned the science for treatment—and tirelessly fought for the funding.

On the other hand, I’m thinking in the present tense. We are in a horrifying conservative backlash right now that could really be immobilizing. How can I work and pay my rent, but also bring my skills to all the amazing grassroots organizing happening right now, from prison abolition, defunding the police, affordable housing, canceling student debt, Palestine—all of which are interconnected struggles—to the current onslaught of anti-trans legislation? How can I be of service?

Photographs by Object Studies

Manders: Now you’re reminding me of the rest of the quotation from which you borrowed your title. In an early review of JEB’s Dyke Show, Carol Seajay claimed these were “Images on which to build a future.” This exhibition, like the image cultures it showcases, is as interested in doing as it is in being.

Goldberg: A lot of trans and queer image making was all about self-determination beyond representation.

For example, Loren Rex Cameron, who was a part of the FTM support group in San Francisco, took pictures of people at different stages of transitioning, and those pictures played a part in educating people about hormones and surgeries. His photographs give us a way to understand how people were using photography to share non-pathologizing transgender medicine and build stronger movements.

The “doing” also speaks to how I wanted to share materials about the joy of gathering! I don’t want to lose that aspect of it. I’ve learned that didactic projects are also about community building and fun. Look at ART+Positive’s Queer Beauty series that Lola Flash photographed: people were spelling the phrase with their naked bodies! This isn’t dry material! Enjoyment in education is part of the work.

Courtesy the Artist

Manders: I’m struck by the breadth of this exhibition—the fullness of your curatorial essay and exhibition text and even acknowledgments. We’ve joked about our shared “maximalist tendencies.” It’s not an inability to edit but, instead, a commitment to community, pedagogy, and material history.

Goldberg: Captions are a great metaphor for my work. I felt inspired to begin research for this exhibition while I was working on my photo history book Just Captions: Ethics of Trans and Queer Image Cultures. The caption is my rallying call to learn the names of people who appear in images. To then ask questions about how they were showing up for movements. Beyond the literal, I think of captions as an expandable poetic space, as curiosity for multiple narratives.

The show demonstrates how people were supporting and making culture. The columns in the exhibition space are wheat pasted with a single flyer or newsletter page from each of the six sections of the show. The Electric Blanket slideshow call for photographs, Rupert Raj’s Metamorphosis, which was the inspiration for Lou Sullivan’s FTM Newsletter. I want to show how these projects addressed their audiences. Wherever possible, I included a review of the slideshow or exhibit, in part to prove the work was recognized in feminist, trans, and queer communities.

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the Sexual Minorities Archives, Miscellaneous Photography Collection and Digital Transgender Archives

Manders: That makes me curious about the echoes and reverberations of these image cultures. How do we see their influence in the years after? And today?

Goldberg: We see the influence of these image cultures where artists are distributing their work in unconventional, non-institutional ways that also foreground material struggles and support their peers. Publishing hard-to-find materials online, with captions, for example, and making it freely accessible, as Sky Syzygy’s Gender.Network website does.

I am excited by contemporary work that tries to understand, through photographs, the texture of the lives that we’re now celebrating, as opposed to relying on iconicity and fantasies. If we insist on context as part of the work, we can resist the erasure of material struggles that often happens when queer culture is appropriated into mainstream culture.

The exhibition highlights inherited strategies of practical resistance, ways to fight the violence and stigma and discrimination that come with a denial of queer and trans life and history. Image makers and archivists in the timeframe I’m looking at realized that they have skills in documenting and preserving queer history and organizing, and needed to put those skills to use.

Courtesy the artist

Manders: Can you give us a contemporary example of that formula in action?

Goldberg: Here’s one that was really moving: this student, Avery Camp, is in a class I’m teaching at the New School, and we went to the archives at the LGBT Community Center in New York to look at periodicals. Their assignment was to make a newsletter, message, poster, or sign. Avery made a flyer with information about how to volunteer for the Trevor Project, which is currently dealing with a high volume of calls and a lack of volunteers.

I asked the museum to distribute Camp’s flyer at the exhibition. J. Soto, director of engagement and inclusion at Leslie-Lohman, printed it in a handbill size for visitors to take and spread the word. That’s the legacy right there. You don’t need a lot of people to get something done. It’s not that complicated. Let’s do something now.

Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s is on view at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, through July 30, 2023.