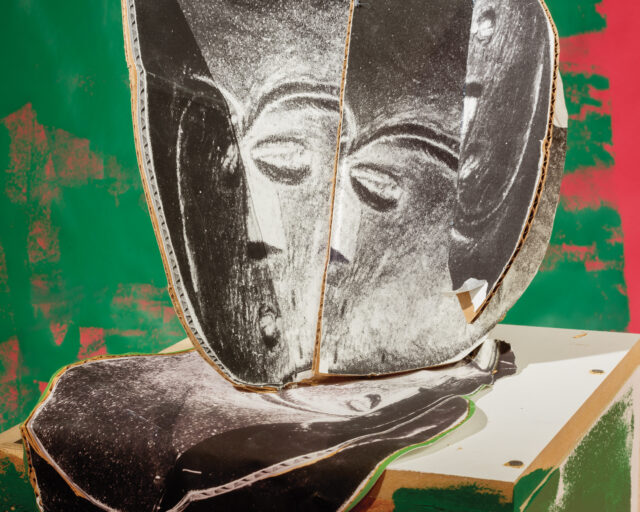

Shikeith, Prince, 2019

Courtesy the artist

It is the picture of rebirth, an image of the unease of transition. Profusely the sweat gathers, beading across Prince Luxury’s face and chest. His almond-shaped eyes are shut as his tongue reaches across gold grills capped onto his teeth, licking away moisture from his upper lip. His body is there in the frame, but his mind is elsewhere. Looking at the artist Shikeith’s image titled Prince (2019), you want to see what the figure sees, but you can’t. Luxury’s gaze is hidden behind his eyelids; like an awning, they provide cover. What vision is he masking? An action of his own making? An imagined destination where the sweat of his labor marks him of value? A place where he is the center of his own desire? Of this image, Shikeith has noted that he seems to have caught Luxury in the middle of “an act of deviance.” What is captured is an autoerotic freedom.

Utopia is not a word that has been widely considered in the contemporary photographic works of Black queer artists. Much of their art has been flattened into the politics of representation. But Shikeith’s impression of ecstasy is an ideal, a warm depiction that insists on concrete possibility for another world. This work has roots in earlier art that explores subjectivities and social spaces beyond cultural and sexual limitations. Alvin Baltrop snapped black-and-white pictures while cruising New York’s collapsing Hudson River piers in the 1970s and ’80s. Those images reveal a secret world—in the liminal post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS space—that existed outside of that era’s dominant sexual appetite and presaged today’s wide embrace of dating apps such as Grindr and Tinder, and casual sex-worker sites like OnlyFans. Shikeith’s portrait of desire also recalls Lyle Ashton Harris’s images that parse gay male subjectivity and want. Harris’s early 1990s performances of masculinity transgressed the binaries of gender and race that governed how a Black man should act. In a self-portrait, Snow Queen #1 (1990), Harris appears in a platinum blond wig; white powder covers his face. His body does not yet exist as normal; there is no place where his body can feel affirmed and complete without the possibility of harm.

© and courtesy the artist

While utopia often denotes otherworldly fantasy, unrestricted escapism, or sublime positivity, the late theorist José Esteban Muñoz, in his 2009 book, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, offered the idea of a queer utopia, one constructed with verisimilitude and operating against a history of lack and discrimination. Queerness belongs to the future, Muñoz claims in his study of performance, writing, and contemporary art, noting that it “allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present.” Utopia is the search for safe space in counternarratives where queer acts, longings, and urges fulfill personal and communal yearning—and where desire flourishes beyond the confines of mainstream white, gay culture. Such acts offer care and delight, a way out of the margins. As Joshua Chambers-Letson, Tavia Nyong’o, and Ann Pellegrini write in their foreword to the 2019 edition of Cruising Utopia, “For utopia, though it bears many positive qualities, also bears negation, as originating from the Greek for ‘no place’ or ‘not place.’” They add, “Queer utopia is the impossible performance of the negation of the negation.”

“When idealizing what utopia looks like I immediately think of the use of photography,” the photographer Davion Alston explains to me. “This tool mastered the recording of truth, the reflection of what or who could be.” Alston’s recent series stepping on the ant bed (2020) documents the protests in Georgia against the killing of unarmed Black people such as Rayshard Brooks and Breonna Taylor by the police. He describes the work as a way for him to explore “desiring utopia in dystopia.” These black-and-white images capture protesters as they shut down southbound lanes of the I-75/I-85 highway. In the photographer’s prints, faces are intentionally obscured with blue, red, yellow, and green stickers. “Through this covering of faces,” he says, “I am able to think about the protection of identity due to surveillance and speculation as well as redefining what the landscape looks like in 2020.” The images allow for new imaginings of the expressions of the Black body beyond what is sanctioned. Amid the twin pandemics of racism and coronavirus, the pictures offer a look at seeking safety in protest, a way of gathering against governmental failure.

Courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures Generation, New York

“I made the image knowing I wanted to talk about not giving a fuck,” the photographer D’Angelo Lovell Williams says of Nah (2018). It’s a self-portrait of the artist in a white dress, swimming in a lake, away from the camera, a gesture that refuses capture, finitude. The image is part of a growing oeuvre in which Williams creates scenes of aspiration and connection. “When I think about the formal,” he explains, “I think about themes of class, race, and social hierarchies that don’t allow Black and queer people to explore beauty and desire of each other’s bodies.” His aim is to reframe that censorship, visualizing what Muñoz addresses as a queer performativity that “is not simply a being but a doing for and toward the future.” In Elysian (2018), a figure obscured by parched foliage is seen tenderly pulling a lover into another world, where a moment of intimacy is possible. There is a radical physicality present that explores themes of surreal dualities, kinship, and discovery as a way to transgress the taboo. “I know our history with the natural landscape, and it’s lacking in regard to visual representation,” Williams says. “When themes about my work come up, I hear, ‘Oh, well, your work is sexually explicit.’ The gestures are about rejecting the labels that have been placed on us. I don’t have to abide by censorship on my own body or people’s bodies.” He adds, “It’s about going beyond a sense of the now.”

Photographers such as Daniel Obasi, Nydia Blas, and Naima Green also use the camera to exceed the present precarious conditions of racism, homophobia, and anti-trans violence. In Green’s portrait Diamond, Brower Park (2016), the subject’s eyes are closed. “That gesture offers a different way of thinking into oneself, the landscape, and creating a utopia in really blocking out everything and just being there and taking a deep breath in the moment,” Green explains. The image is from a series of portraits, called Jewels from the Hinterland (2013 ongoing), that captures creatives from across the African diaspora in urban idylls. Hinterland: an area lying beyond what is visible or known. This idea of a private space, only reachable by those in the know, was essential to Green’s pursuit to “create an alternative present” and “reclaim lively, lush urban space as Black space.”

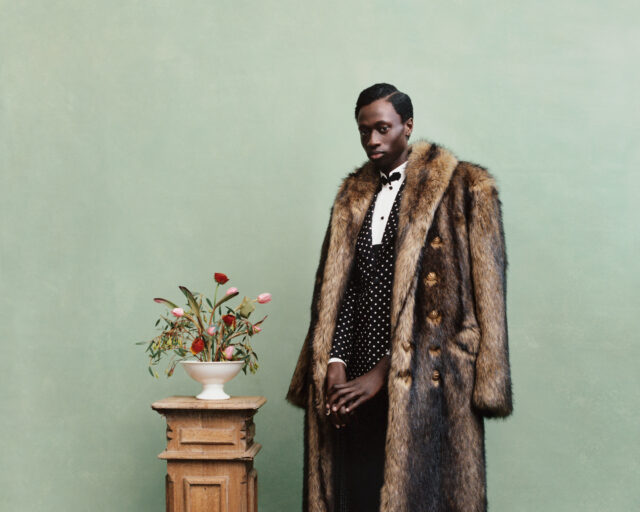

Courtesy the artist

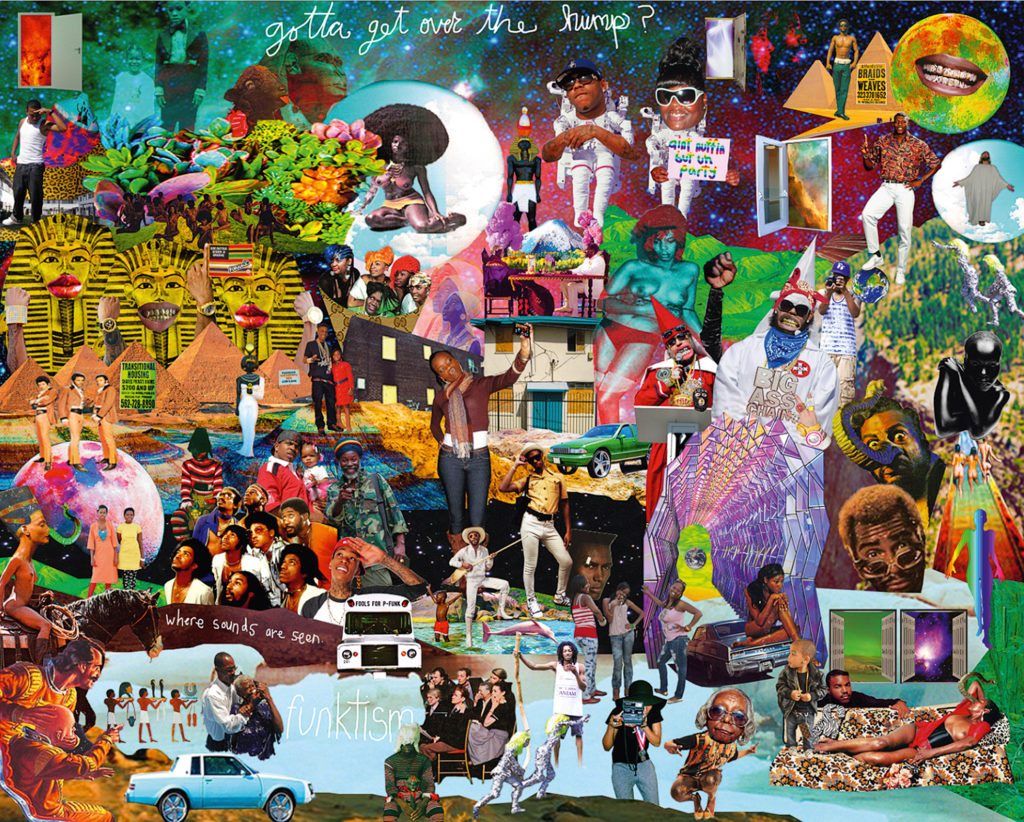

Reclaiming urban space as Black space is also at play in Lauren Halsey’s digital collages that present queer Afrofuturist alternative realms. On social media, she borrows the name of the Black ready-to-wear label FUBU (For Us By Us) that, in the 1990s, represented cool urban self-realization, and hashtags her visions #fubuarchitecture. For the artist it seems to be shorthand for what an inclusive and self-reliant Black community could be. Her work thang (2020) zeroes in on South Central, Los Angeles, where Halsey is from. She remakes her neighborhood in her own image. Stylish Black women and men appear, cut from found materials, as do pyramids, unicorns, statues, a Louis Vuitton–monogrammed California bungalow, and advertisements for local businesses such as Urban Books & Thangs. There are statements of empowerment against gentrification: we still here, there (2018) and the sprawling collage work gotta get over the hump? (2010), in which emblems of Black mysticism and informal communion collide. Halsey’s visual world-building sits in a history of queering the medium of collage that has long manufactured dreams, manifesting them through the construction of new material realities.

Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

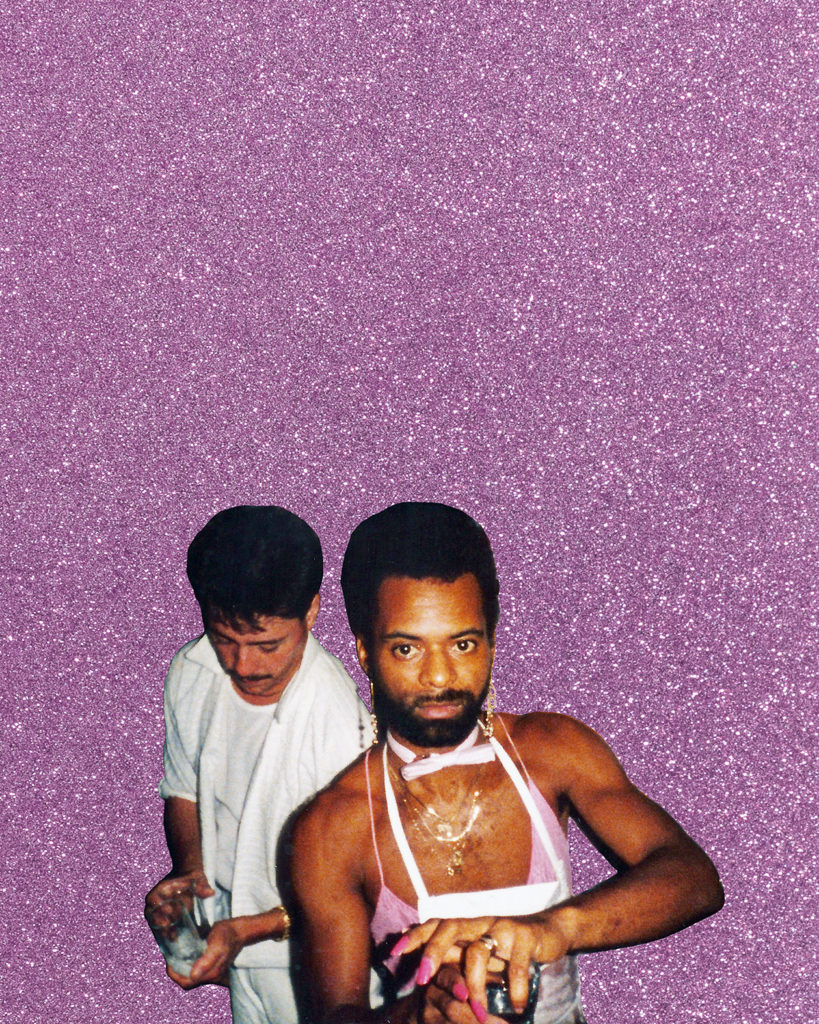

Like Mickalene Thomas, with her vibrant, collaged living-room tableaux, Halsey, who also draws on the Black cultural aesthetics of the 1970s, has used her collages as sketches for architectural installations such as Kingdom Splurge (2015), which she describes as an “endless becoming that entails liberation through Funk, fantasy architecture, and the experimental development of space.” A similar impulse is at play in Sadie Barnette’s New Eagle Creek Salon (2019). The project pays homage to and reimagines the San Francisco bar her father, Rodney Barnette, opened, in 1990, to serve a multiracial queer community marginalized by the city’s gay nightlife scene. The installation’s bar (activated as a social space), sculpture, and found party photographs of patrons and bartenders are glittering documents of history. Memory here is used in the service of futurity—or, as Barnette writes, the project is meant to “offer space for connection and new energies, to dance and dream.”

Courtesy the artist

Muñoz opens Cruising Utopia with a provocation: “Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality. Put another way, we are not yet queer.” It announces that queer people are not yet fully themselves in the world, and the process of trying to get there is the hard work of hope. The violence of the state routinely smashes the self, controlling what is possible—sexually, politically. Given this enduring reality, some queer artists dream in images, in defiance of the straight imagination. Their eyes desire narratives of longing and pleasure, free of trauma, with illuminations of relief. Through their pictures, other ways of existing are possible.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” Winter 2020, under the title “The Future Will See You Now.” Read more from the issue, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.