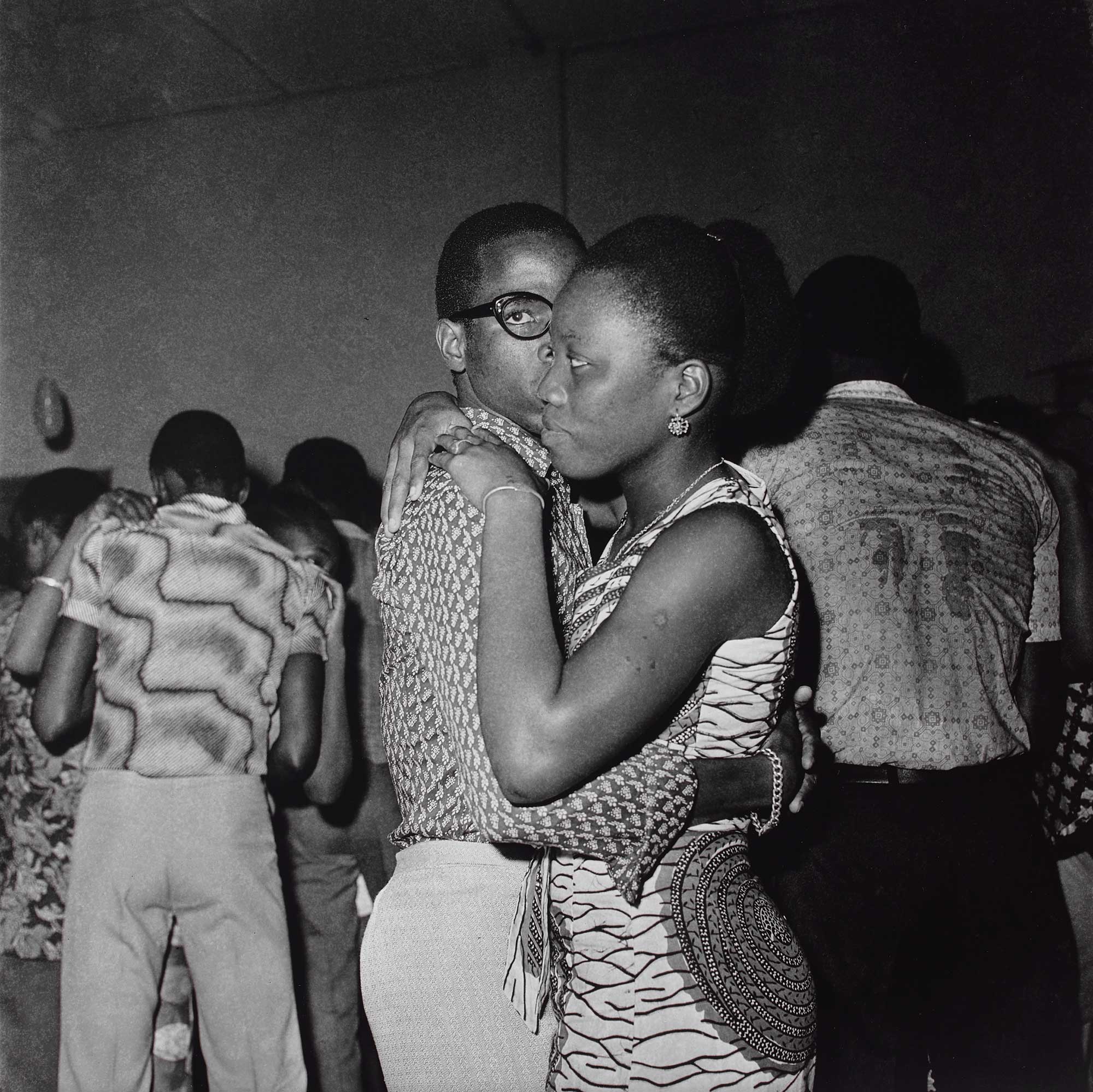

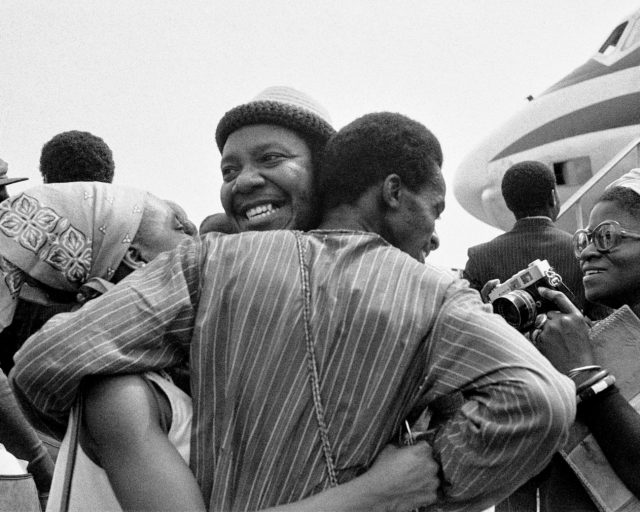

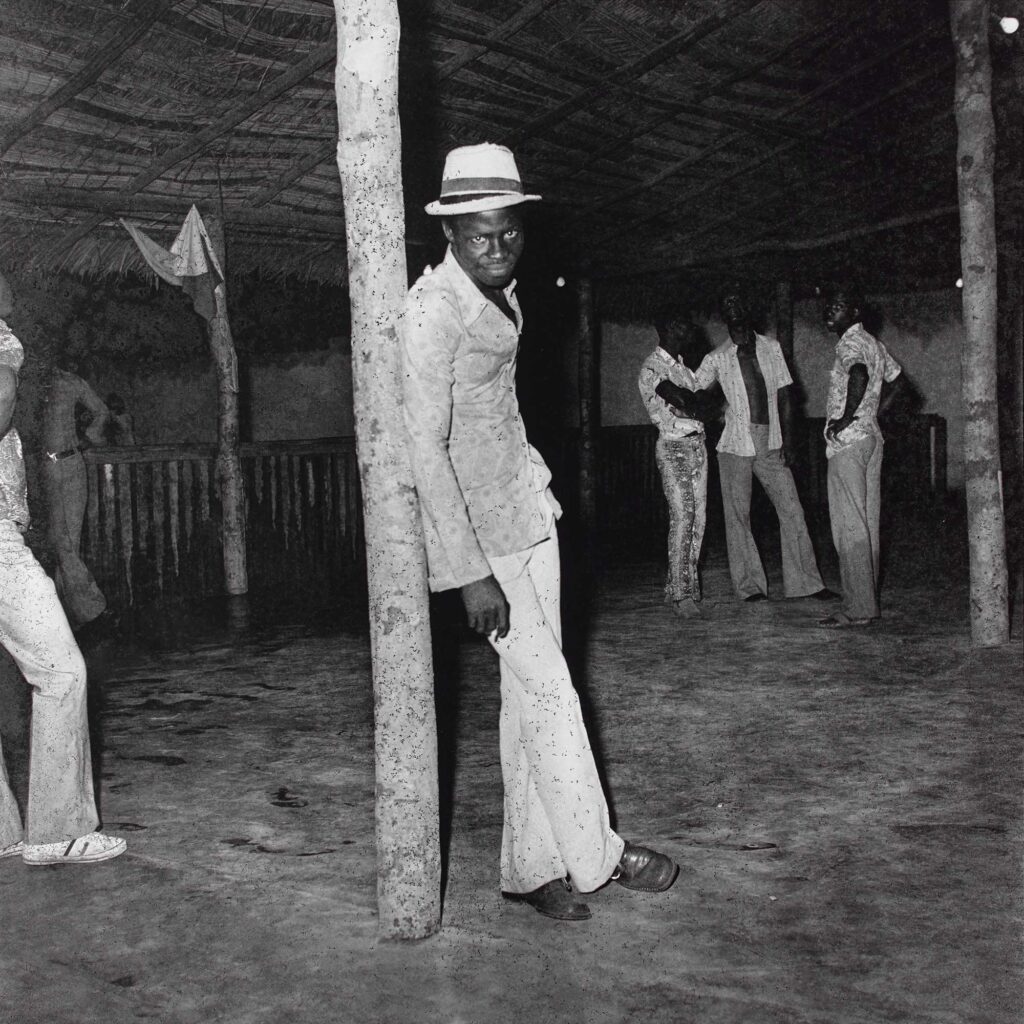

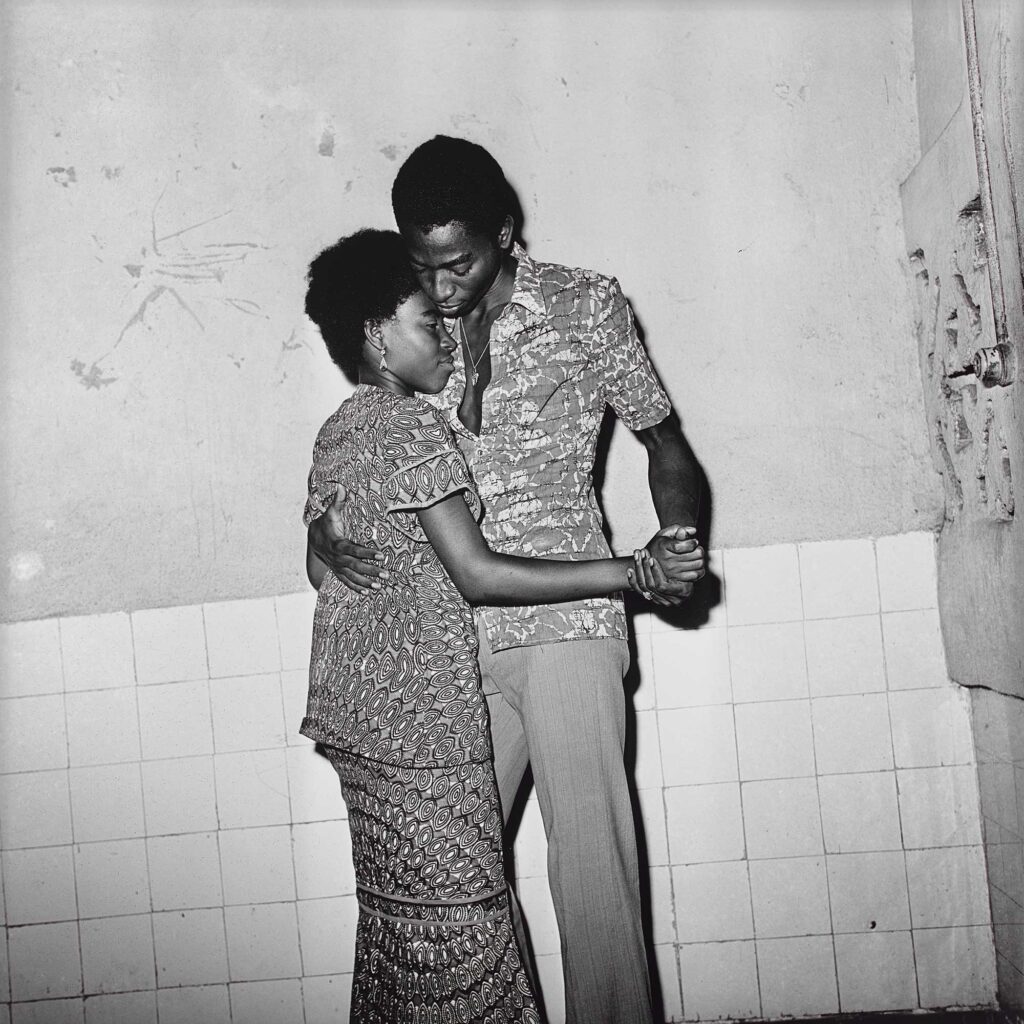

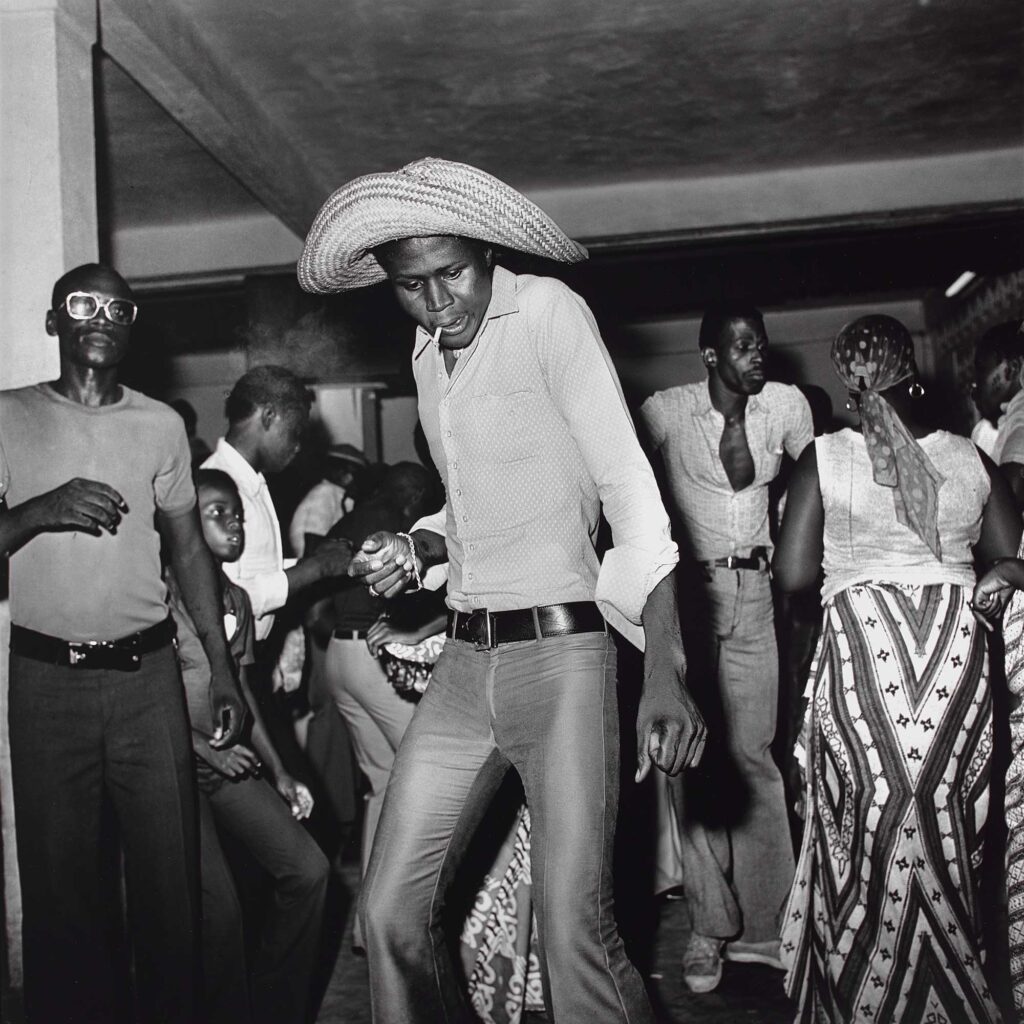

Paul Kodjo, Untitled, 1970s

Paul Kodjo’s work was headed for the dustbin of history—not the proverbial trash can but the actual garbage. The 2022 documentary Je reste photographe (I remain a photographer) shows a scene with the Ivorian photographer, his daughter Esther Kodjo, and the film’s director, Ananias Léki Dago, in a wooden cabin that the elder Kodjo built in a forest in Elubo, Ghana, where he retired. The trio are sifting through a dusty iron trunk filled with deteriorating papers and negatives, along with dirt, leaves, dead spiders, and cockroaches. “Ananias, this is what’s left of my work. I’m giving it to you. Do whatever you can with it,” Kodjo says. “Or else, I’m throwing it away.”

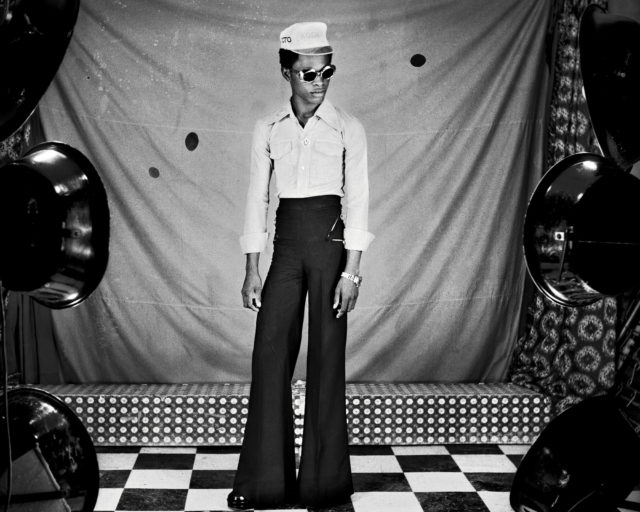

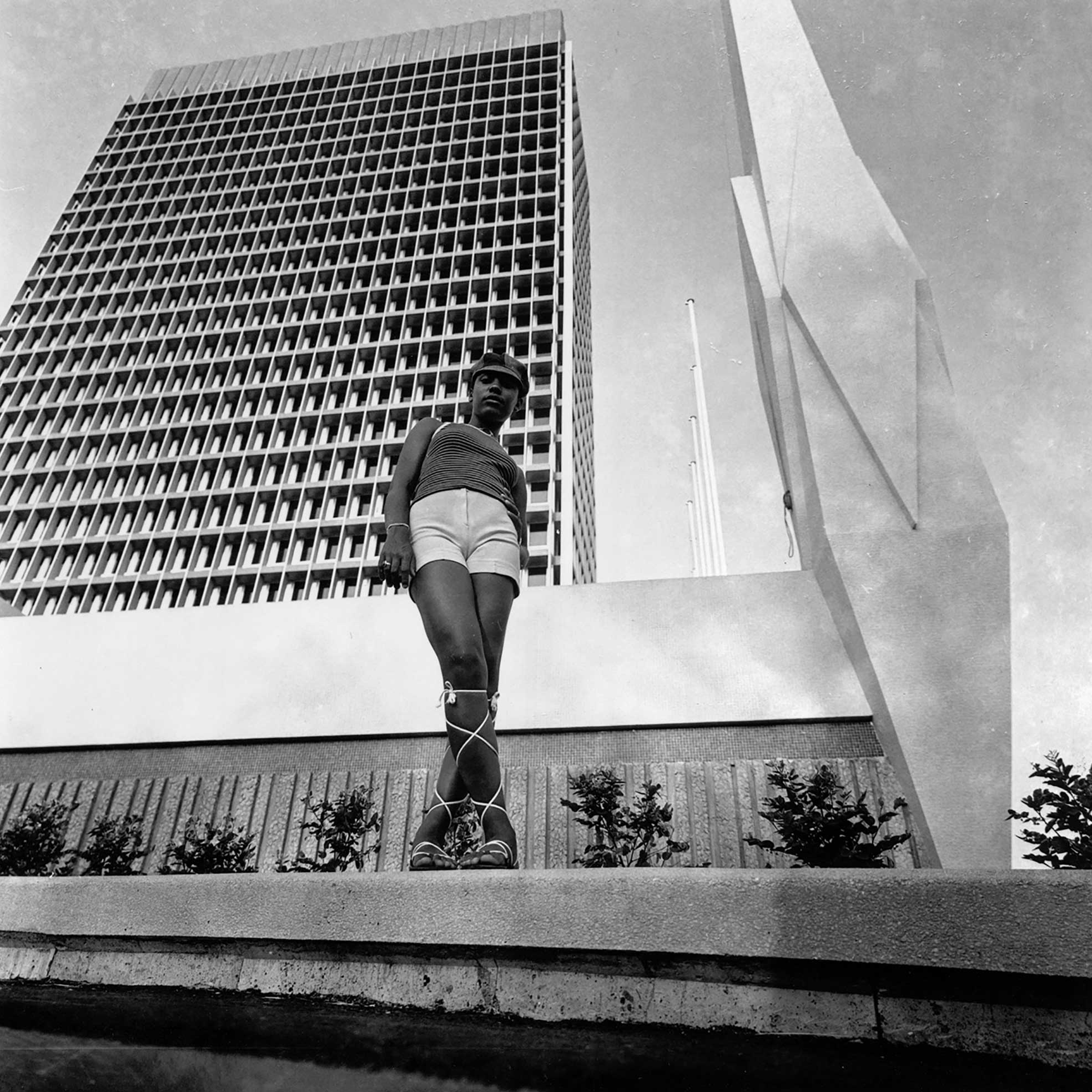

Léki, who is also a photographer, has been working to restore, archive, research, and promote Kodjo’s work internationally since they met in 2002. Kodjo’s photography from the 1960s and 1970s features fresh, emotive, black-and-white portraits of young people in the streets of Abidjan, Ivory Coast, and in gleaming domestic settings. Kodjo, who died in 2021, began his career in 1959, on the eve of Ivory Coast’s national independence, following French colonial rule, and his images capture a mood of aspiration during a postindependence economic boom. Look what Kodjo could do with angles, as in his electric 1970 photograph of a Black model in front of a boxy building. It strikes me as a visual chiasmus, a moment of reversal caught on camera. The tall building is clearly bigger but the model seems to rival its grandeur.

“I want his story to be known around the world,” Léki told me over Zoom last winter. Most of us would have never known of Kodjo’s photography without Léki. But this is not a savior story, not a rescue narrative, not the artistic neocolonialism that often governs records of African art. It’s a political commitment involving an Ivorian artist protecting and fighting for the legacy of another living Ivorian artist. Léki has opened new vistas onto Kodjo’s cultural, historical, and aesthetic impact on photography in Ivory Coast and around the world.

“People thought that he was already dead—dead physically and also photographically or artistically,” Léki said. “From what I know from the history of photography, I’ve never heard of another African who saved another African’s archives.” He continued: “For me the message of that is also political. It’s unique: an African photographer who helped another old African photographer, who restored negatives without any validation from the West until they bite. It’s a victory. I’m not in the big system. Paul Kodjo is not a product of the Western. Malick Sidibé is a product of the Western. Seydou Keïta is a product of the Western.”

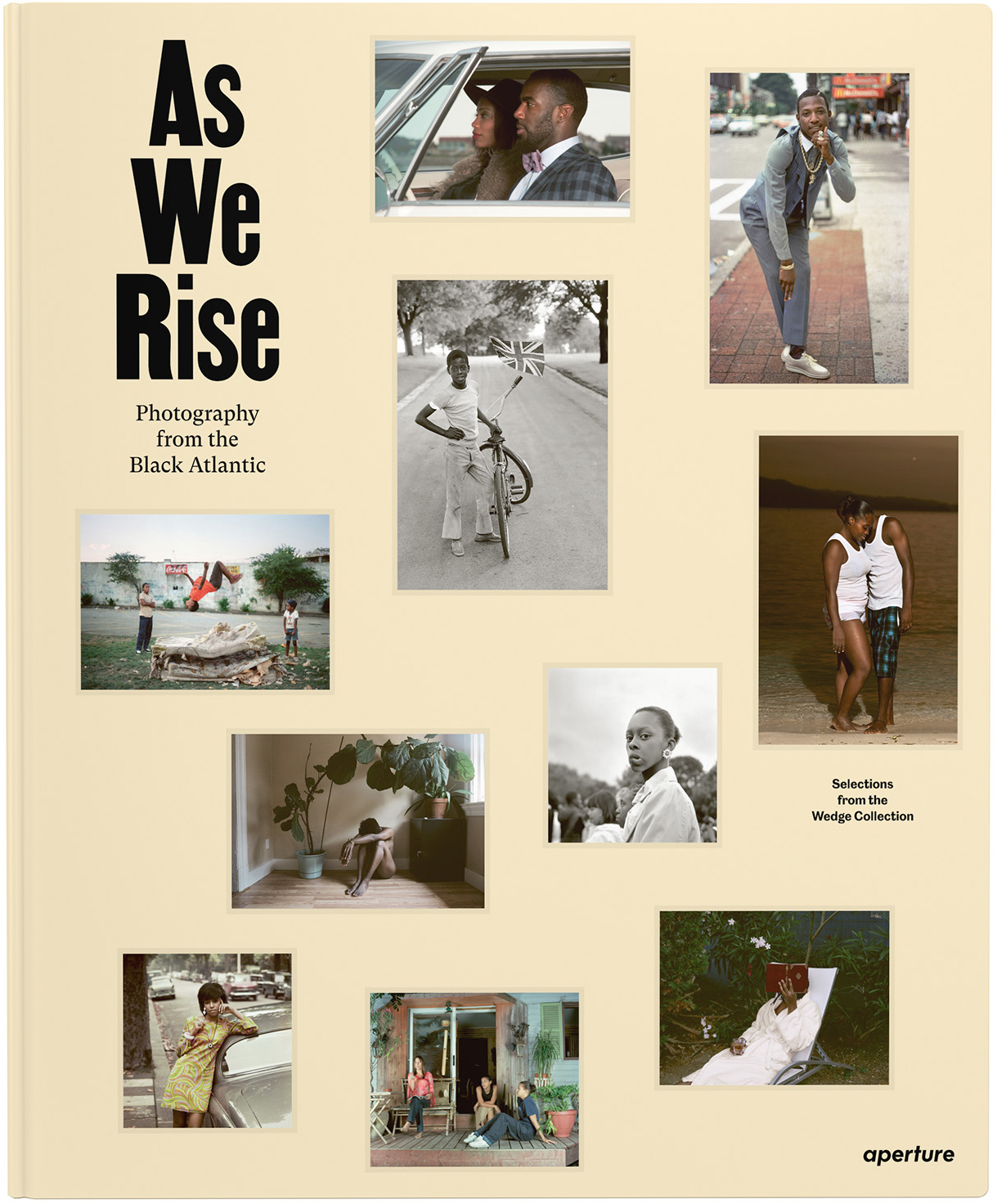

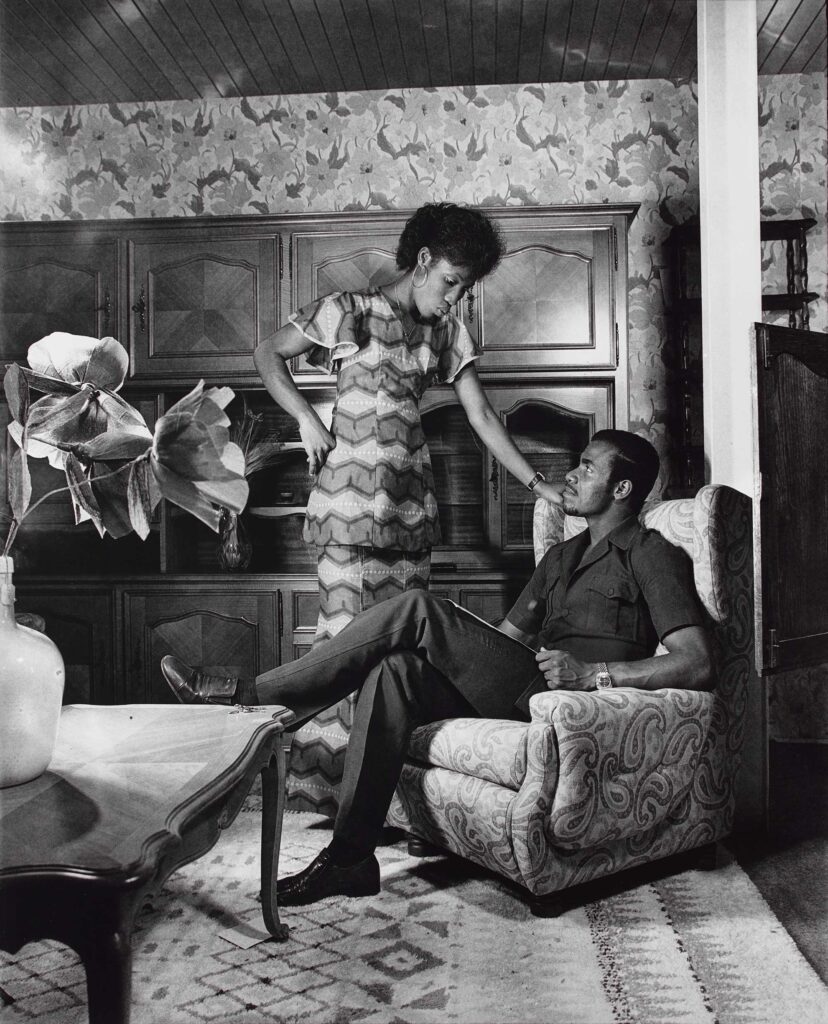

You Look Beautiful Like That: Studio Photography in West and Central Africa, an exhibition recently presented by the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), Toronto, includes only two images by Kodjo, but these stand out among the very well-known work of Malian photographers Sidibé and Keïta, as well as Cameroonian photographer Michel Kameni, among others. Kodjo’s images are photoromans, an innovation that boomed in the mid-twentieth century and features textual narrative paired with photography. Kodjo, who was born in 1939, began using this kinesthetic format in the late 1960s and early 1970s for work published in the magazine Ivoire Dimanche. With its use of scripts, castings, settings, and amateur and professional actors, this cinematic approach to still photography is no surprise given that he studied film in the 1960s in Paris and once wanted to be a filmmaker.

Kodjo’s story is part of an intergenerational narrative about the difficulties of keeping Black archives alive in an oftentimes exploitative art industry.

“Kodjo wasn’t necessarily a studio photographer. He creates these beautiful cinematic mise-en-scènes,” says Julie Crooks, the AGO’s curator of arts of global Africa and the diaspora who organized the show. “It’s very filmic. It blurs the line between reality and fiction and lands somewhere in between.”

The exhibition’s main title is translated from the Malian phrase “I kany¨ tan.” It was popularized by Keïta and was previously used as a title for an exhibition, traveling from 2001 to 2003, of works by him and Sidibé. The words stress, as Crooks tells me, “the idea of collaboration between client and photographer, which is different than the kind of ethnographic images that we associate at that time through the lens of European photographers that create these damaging stereotypes of African peoples.”

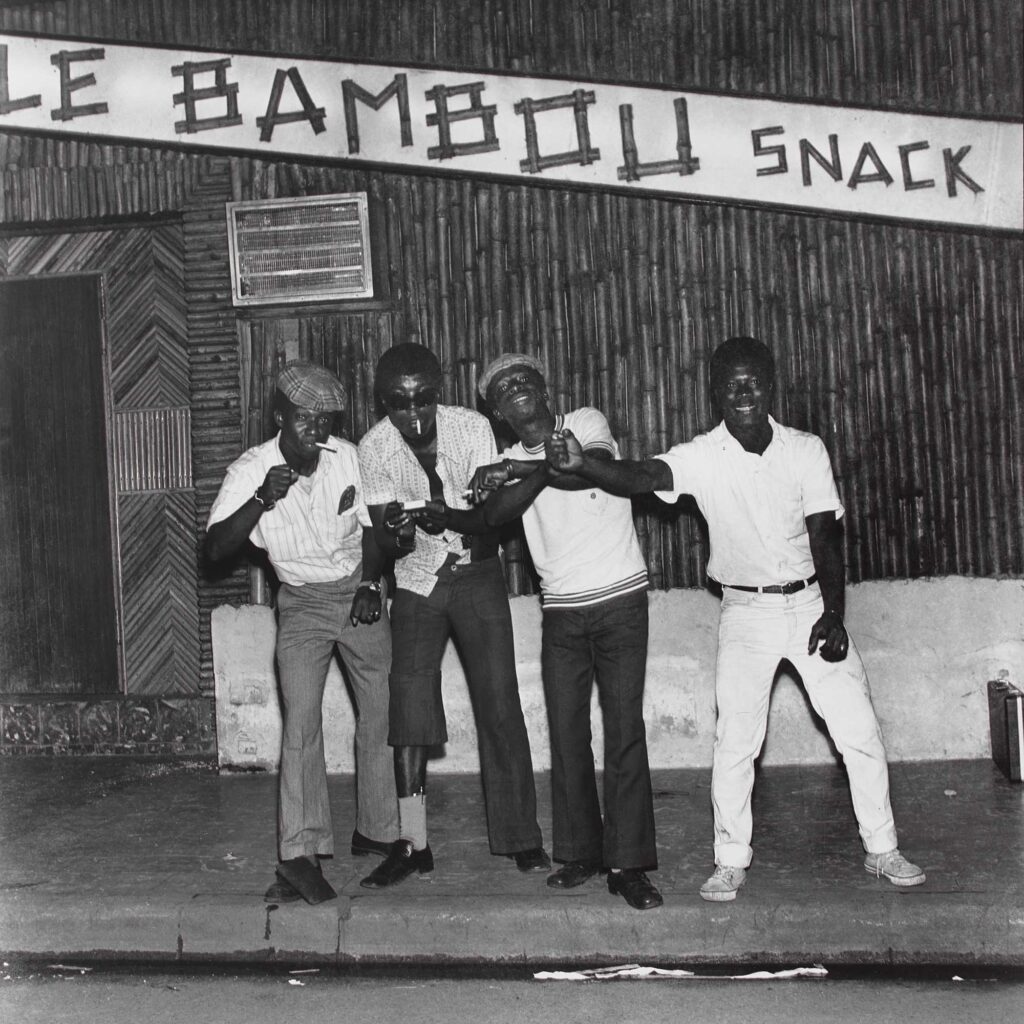

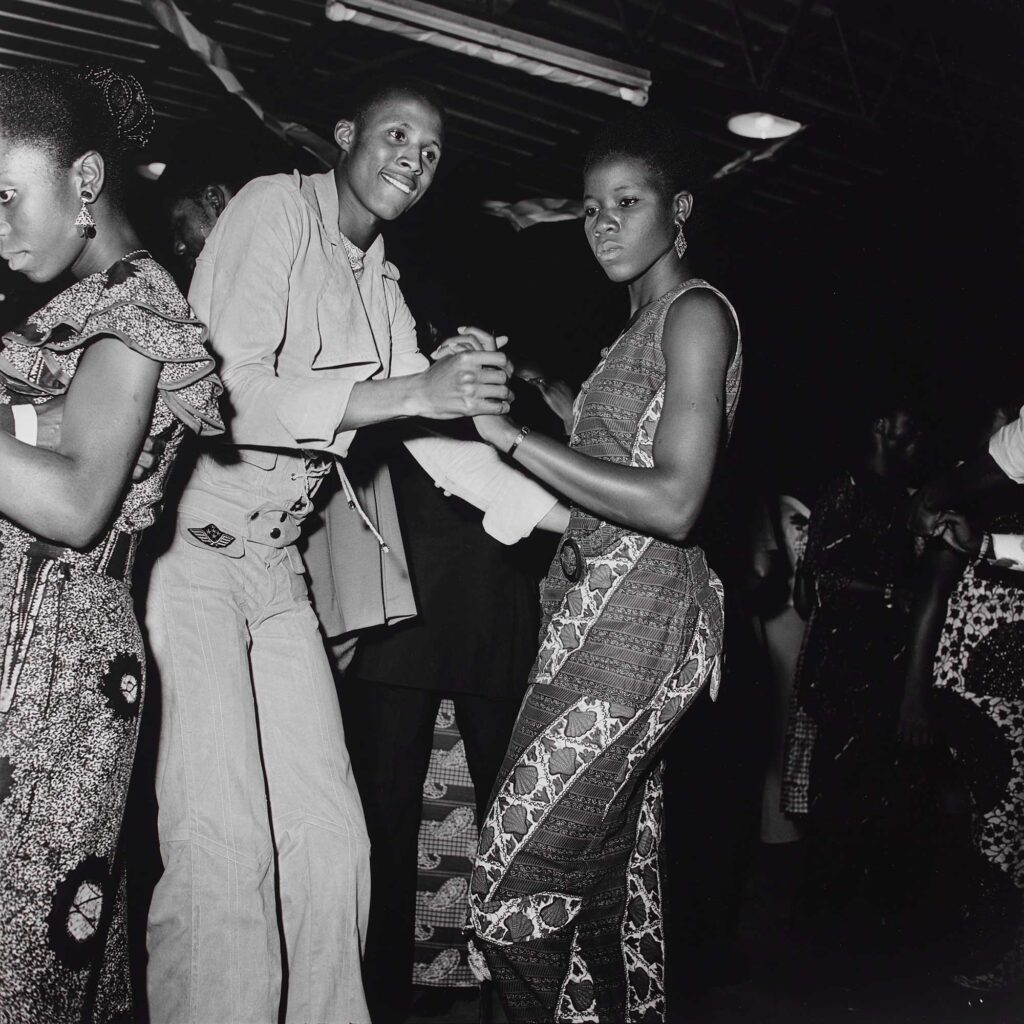

Self-presentation, modernity, aspiration, self-propulsion, confession, and the politics of respectability are at the heart of studio-photography practices. Studio photography limns the line between self-determination and conformism, intimate and public life, performance and the mundane. By contrast, Kodjo’s photos of nightlife and youth culture especially are edgy, resisting cultural norms of the time. “Crazy, unbridled, carefree, and cheerful,” says Léki in the documentary, narrating over a slideshow of Ivorians dancing, partying, flirting, touching, swaying, smoking, self-fashioning, hugging, and posing. Kodjo also worked for the press, photographing the political elite, and he was the only Black African photographer to cover the May 1968 revolution in France, assigned by a government news agency created by then President Félix Houphouët Boigny.

All photographs © Estate of Paul Kodjo and courtesy Les Rencontres du Sud

Often referred to as the “father of Ivorian photography,” Kodjo rocketed to prominence in the 1960s and 1970s with his photoromans. But after much popularity, he disappeared from public view. “He was born in the period that people didn’t understand what he was doing,” Léki told me. “He was faster than his contemporary people.” He seeks to put Kodjo back on the map. The restoration process, which was carried out in France, has been long—and many negatives were lost. But the 3,120 photographs that remain tell a powerful story about Ivorian history and aesthetics. Kodjo’s story is part of an intergenerational narrative about the difficulties of keeping Black archives alive in an oftentimes exploitative art industry. “I know some institutions in the West are not happy because they’re like, What is this Black young man doing? Is he challenging us? I want to control the narrative,” Léki insisted. “I don’t want anyone to take that from me—or from us.”

You Look Beautiful Like That: Studio Photography in West and Central Africa is on view at the Art Galley of Ontario, Toronto, through June 11, 2023.