The Struggle for Survival in the Amazon

Claudia Andujar has advocated for the Yanomami people throughout her career. In a major exhibition, her photographs coexist with Indigenous voices.

Claudia Andujar, Self-portrait, Catrimani, 1974

© the artist

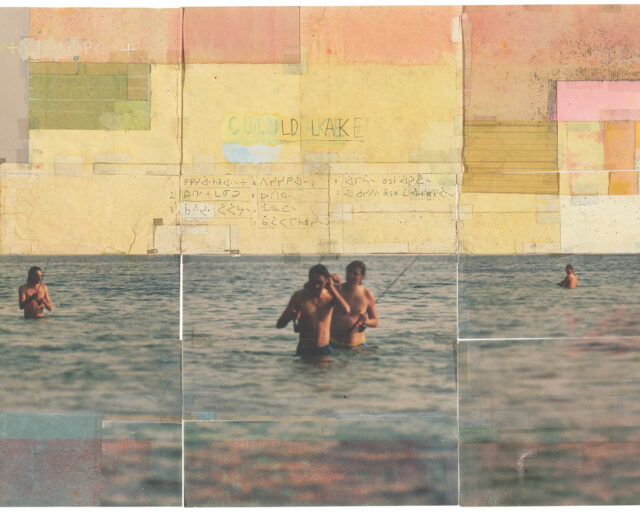

For more than fifty years, the photographer Claudia Andujar has collaborated with, advocated for, and photographed the Yanomami, the Indigenous people who inhabit a swathe of Amazonia that stretches across Brazil and Venezuela and face dire threats to their autonomy and survival from settler farmers, illegal gold miners, and malignant right-wing political forces. The Yanomami Struggle at the Shed in New York is the latest iteration of an exhibition that features more than two hundred of Andujar’s most iconic and striking photographs of the community as well as videos and more than eighty drawings and paintings by Yanomami artists.

Since first meeting members of the Yanomami in 1971, Andujar has attempted to capture the daily life and spiritual essence of Yanomami worlds with experimental photographic techniques, using infrared film, saturated-color filters, and lens and exposure manipulations to translate their lifeways and spiritual systems for outsiders. Andujar has dedicated most of her life and career to the Yanomami cause and their communities as a singular subject. Yet despite Andujar’s sincere belief that images can help protect these people from the encroachment of coloniality, a lingering tension consumes her work. She attempts to represent both worlds foreign to her and sites of struggle through a lens that carries the baggage of ethnography’s most romanticizing and preservationist impulse—that her subjects’ value is in their being untouched by modernity.

© the artist

Unlike recent iterations of this traveling exhibition, this tension finds some relief in the Yanomami artworks that visualize not only the community’s life and cosmological worlds but also their struggle against the theft and destruction of their land by deforestation, slash-and-burn farming, and strip mining. These contributions do much to counter Andujar’s tendency toward the ethnographic, allowing for her decades-long advocacy-through-representation to operate more collaboratively with Yanomami voices.

© the artist

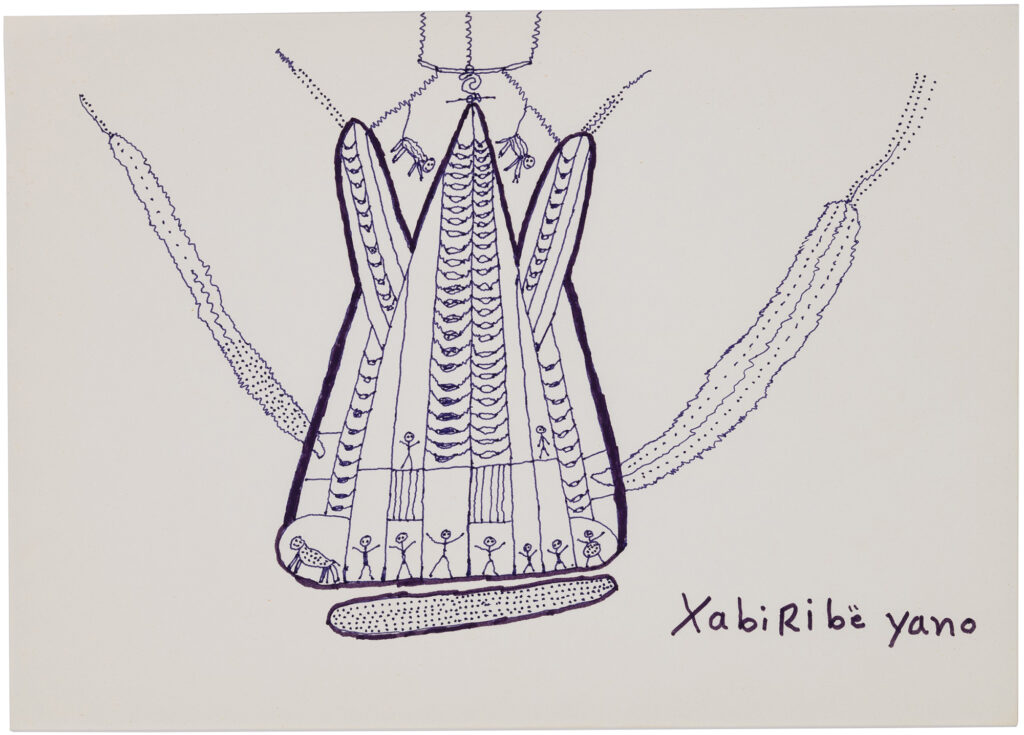

The Yanomami Struggle takes up the entirety of the Shed’s main exhibition hall, which is divided into five spaces that present six thematic sections. At previous venues in São Paulo, Paris, and London, the exhibition presented Andujar’s work largely on its own. In New York, her photographs are juxtaposed with fifty-eight new drawings, paintings, and prints and three new short films by Yanomami artists. Many of these works are from the Fondation Cartier’s collection and are being shown in the US for the first time. Andujar’s photographs are suspended throughout the Shed’s main space, in a constellation of black-and-white portraits and saturated infrared images of Yanomami homes and environs: pink jungle canopies, bright orange and yellow yano (communal houses) surrounded by sweet-potato leaves, and glittering blue waterways and star-covered palm-leaf roofs. Interspersed throughout are figurative drawings in colored pencil and felt pen by Yanomami artists Joseca Mokahesi and Ehuana Yaira and shaman and leader Davi Kopenawa—who depict origin stories and xapiri (spirit helpers) with expressive intensity. The exhibition is no longer dedicated to Andujar’s work and activism, as past iterations have explicitly stated, but rather to “the long-term collaboration” of Andujar and the Yanomami people, as the exhibition’s introductory text states.

Courtesy Fondation Cartier

Courtesy Fondation Cartier

The show has accordingly become less of an anthropological photo essay or biographical retrospective and more of an aesthetic collaboration. Most notable among these collaborators are Andujar’s primary partners in efforts to defend the community, the shaman and Yanomami leader Davi Kopenawa, a central advocate and spokesperson for the Yanomami on the international stage, and the anthropologist Bruce Albert. Both also provide statements on the exhibition labels that explain Yanomami life, culture, and spiritual beliefs.

The tension between solidarity and romanticization remains throughout, however. On one wall are Andujar’s chiaroscuro portraits of Yanomami individuals, titled Moving Identities, which seem to escape the anthropological with intimate framing and dramatical shadowing from the naturally lit yano interiors in which they were taken. Yet the titles straddle portraiture (Moxi Hwaya u thëri, Vital Warasi’s son, 1974–76) and ethnographic modes of description (A young man’s foreskin is tied to his waist with cotton thread, 1974). The section immediately following the main hall, Rites and Vision, is the most fraught, with photographs focused on reahu (funerary rituals). Kopenawa’s description of associated rites, in which shamans “take our image into the time of dream,” is an evocative explanation of the power of image making in Yanomami belief.

© the artist

The Yanomami Struggle was curated by Thyago Nogueira, head of contemporary photography at the Instituto Moreira Salles in São Paulo, where it debuted, with the guidance of Kopenawa, whose voice is the prominent in the explanatory labels. We are left to trust in the collaborative process as to whether images of Yanomami people and rituals are fit for outsiders to view, and must acknowledge the agency of community collaborators. The film Earth Forest Shamans (2014), for example, directed by Yanomami filmmaker Morzaniel Iramarɨ, documents a reahu over the course of one hour, bulwarking against exoticizing impulses with an Indigenous lens.

Multiple Visions, the section of the exhibition dedicated entirely to Yanomami art, comes as a relief. It contains only several portraits of the artists by Andujar. Whereas the drawings in the opening section use figuration to depict Yanomami oral histories and spirit beings, the artists here tend toward abstraction to translate an experience of the landscape and the influence of the spiritual beings that inhabit them. Visions of the world of the xapiri by André Taniki, Vital Warasi, and Orlando Nakɨ uxima, executed in felt pen and colored pencil in the 1970s, are electric fields of vibrating lines and pictographic figures. Recent acrylic paintings and stamped monotypes by Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe depict Atayu ihiupi husipe pesi (caterpillar cocoons) and Moka maimki (frog legs) with repetitions of stunning organic geometries.

The exhibition is no longer dedicated to Andujar’s work and activism, as past iterations have explicitly stated, but rather to “the long-term collaboration” of Andujar and the Yanomami people.

There is, on the one hand, a sense of the artists as informants, in which they illustrate their cosmological worlds for inquiring colonial minds in search of ethnographic data. On the other hand, these Yanomami works are undeniably the emergent forms of an Indigenous modernist movement. The exhibition appeals to a taste for authentic and unmediated Indigenous worlds, but it is transparent about their very real mediation, either by presenting facsimiles of the earliest works on paper, in some cases, or by referring to pens and pencils as the “tools” first provided to these artist-shamans in 1974 by Andujar and Carlo Zacquini to document their worlds on their own terms. Either way, the cosmovisions of Yanomami shamanic practitioners are deployed as opportunities to translate unseen worlds for audiences seeking to be transported to “untouched” sites of wonder.

In the final room of the exhibition, focused on the sections Struggle and Fight and Vaccination and Health, Andujar’s photography transitions to more explicit and straightforward realism to reflect the worsening conditions of life in the Amazon. Even with Brazil’s election of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2022 and the subsequent creation of the country’s first Ministry for Indigenous Peoples, the Yanomami face ongoing invasion by extractive capitalism and encroaching settler-colonial governments. The genocidal overtones of such campaigns are reflected in Marcados, Andujar’s series of numbered identification photographs that depicts the bureaucratic organization of the Yanomami during a critical vaccination program in the 1980s.

© the artist

The terrible potential of such systems is not lost on Andujar, who narrowly escaped the Holocaust as a child, and the show here closes with a multimedia installation based on the 1989 exhibition Genocide of the Yanomami: Death of Brazil. The flashing portraits overlaid with the word morrer, Portuguese for “to die” but also “to fade,” are a culminating visualization of the existential threat to the Yanomami and illustrates how Andujar’s own background has contributed to her half-century-long dedication to this subject and cause. But despite the calls to action by Andujar and others that make apparent the ongoing need for solidarity, there remains the painful and unavoidable irony that the exhibition is organized by the Fondation Cartier, a philanthropic nonprofit funded by the sale of precious-metal jewelry and luxury goods.

“While you destroy, we draw,” Davi Kopenawa said through a translator at an event at Princeton University, several days before the exhibition’s opening. “We contemplate trees trembling, and we observe nature. It is important for you to respect the lungs of the Amazon, to not destroy it, to value this through art. We make art also to protect our land . . . We are drawing, and we are making the white man understand what we do while they are living in the cities.” One might wonder what The Yanomami Struggle would be without Andujar’s photographs, showing only the art, film, and voices of the Yanomami contributors. Perhaps that could be the next iteration of the exhibition, and indeed of Andujar’s activism itself, allowing for the ally and her image making to fade into the background while the Yanomami express, through drawing and political action alike, full sovereignty over their representations and lands.

The Yanomami Struggle is on view at The Shed, New York, through April 16, 2023.