At most parties, the really good stuff happens in the bathroom. And so it was at a gathering in a tenement on East 9th Street in New York’s East Village one evening in March 1982. Gracie Mansion, a downtown fixture who had appropriated the mayor’s residence for her name, made a gallery out of her water closet, called it the Loo Division, and filled it with prints by her friend, photographer and artist Tim Greathouse. Everybody seemed to visit, including Melik Kaylan, who reviewed the show for the Village Voice and thereby anointed the gallery. It must have felt like any number of futures were beginning.

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Sixteen years later, Greathouse would be dead of AIDS, along with countless others who had seen their world reflected in the photos on Gracie’s walls—in Work Prints (1982) and, later, another show in the Gracie’s permanent space on St. Mark’s. Or who had seen early work from Jimmy DeSana and Zoe Leonard at Greathouse’s own gallery, Oggi Domani, the first in the East Village devoted entirely to photography. Or who had taken in the visual identity Greathouse as a designer developed for Marlborough Gallery and other clients. Those who survived the plague, however, wouldn’t see much more of Greathouse’s own work. He tended to champion other artists over himself, and when he died at the age of forty-eight without a proper estate, his high-contrast black-and-white portraits and graphic works on paper (and the odd sculpture) were returned to the apartments of his devoted friends, unremembered by the downtown art world Greathouse intensely, if only briefly, did so much to encourage.

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Until now. Albeit, currently on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, offers a new view of Greathouse that centers his own electric body of work. Gathered with crucial assistance by Mansion and Greathouse’s longtime friend and roommate Sur Rodney (Sur), Albeit includes a few fine late paintings which now look like relics of activism, in which stenciled letters hector “AIDS” à la Gran Fury’s bittersweet swipe of Robert Indiana; or the lyrics to “We Shall Overcome” breaking apart like a Christopher Wool, fighting to be seen in fields of jaundiced yellow, or perhaps submerged under blood-red blurred boxes. “Ecce Homo,” says a dark piece from 1988, and it’s tough not to see faces of the dead in the blank spaces around the command.

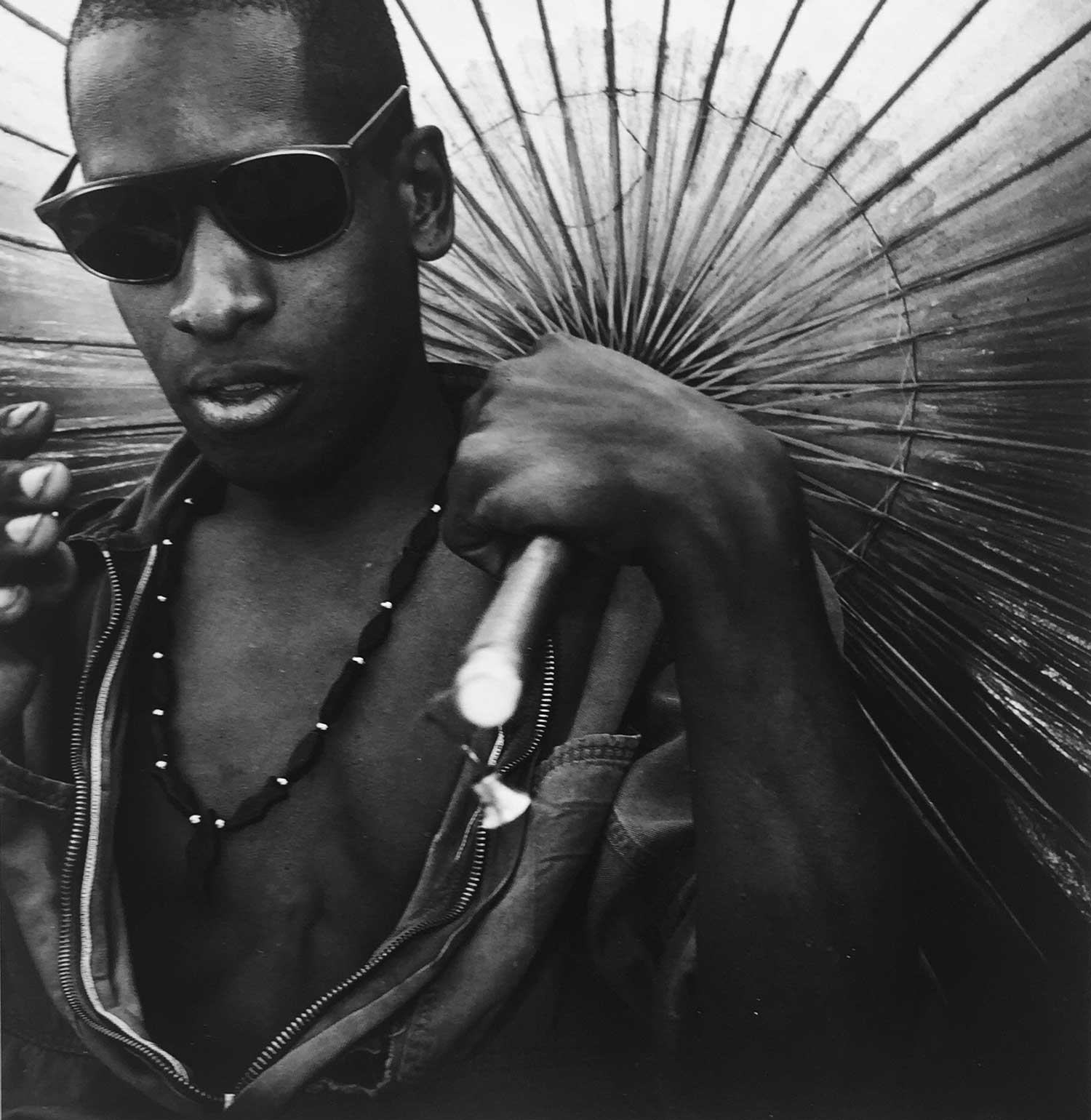

Indeed, faces form the heart of this show, vibrating so strongly in Greathouse’s gelatin-silver prints that the photographs almost become holograms. Two barely contain Sur Rodney (Sur); both taken at Gracie Mansion Gallery in 1983, they show him either boldly wearing big sunglasses and carrying a paper umbrella, or just staring down the lens at the center of it all. “It never felt like I was posing,” Sur told me recently. “We were living in the midst of drug trade and guns on Avenue C.” Greathouse had moved into a storefront his friend Larry Loffredo rented, but because it was a commercial space, he had to open a business. “So why not a photo gallery? He could live illegally in the back, something easy for him because all his belongings could fit into a file drawer,” Sur says. “He was a minimalist monk.”

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

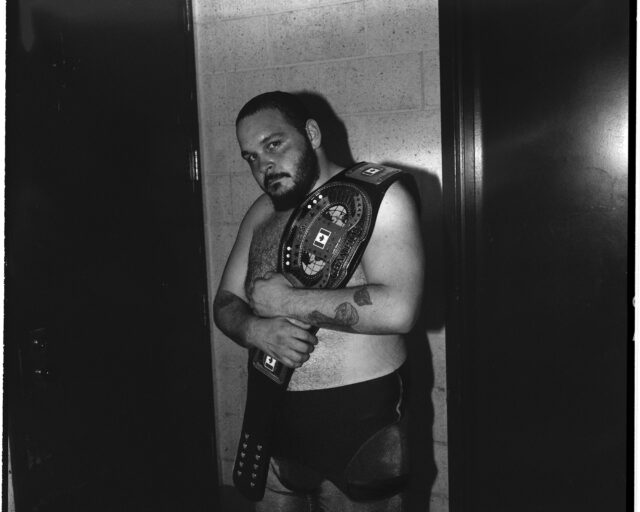

A monk with a keen eye for cropping: Greathouse’s portrait of Larry Loffrado is equal parts chest and head, with a stiff shadow parallel to his jawline. The image is coolly formal, like the bust on a coin you’d spend on a dime bag. In one portrait, artist Rhonda Zwillinger emerges from the shadows like a Hollywood star getting her first break; in another, she goes full Farrah Fawcett, in a black swimsuit so dark it creates one triangle for her chest and another for her arm—akimbo, as if the glamor of her body were a mathematical fact.

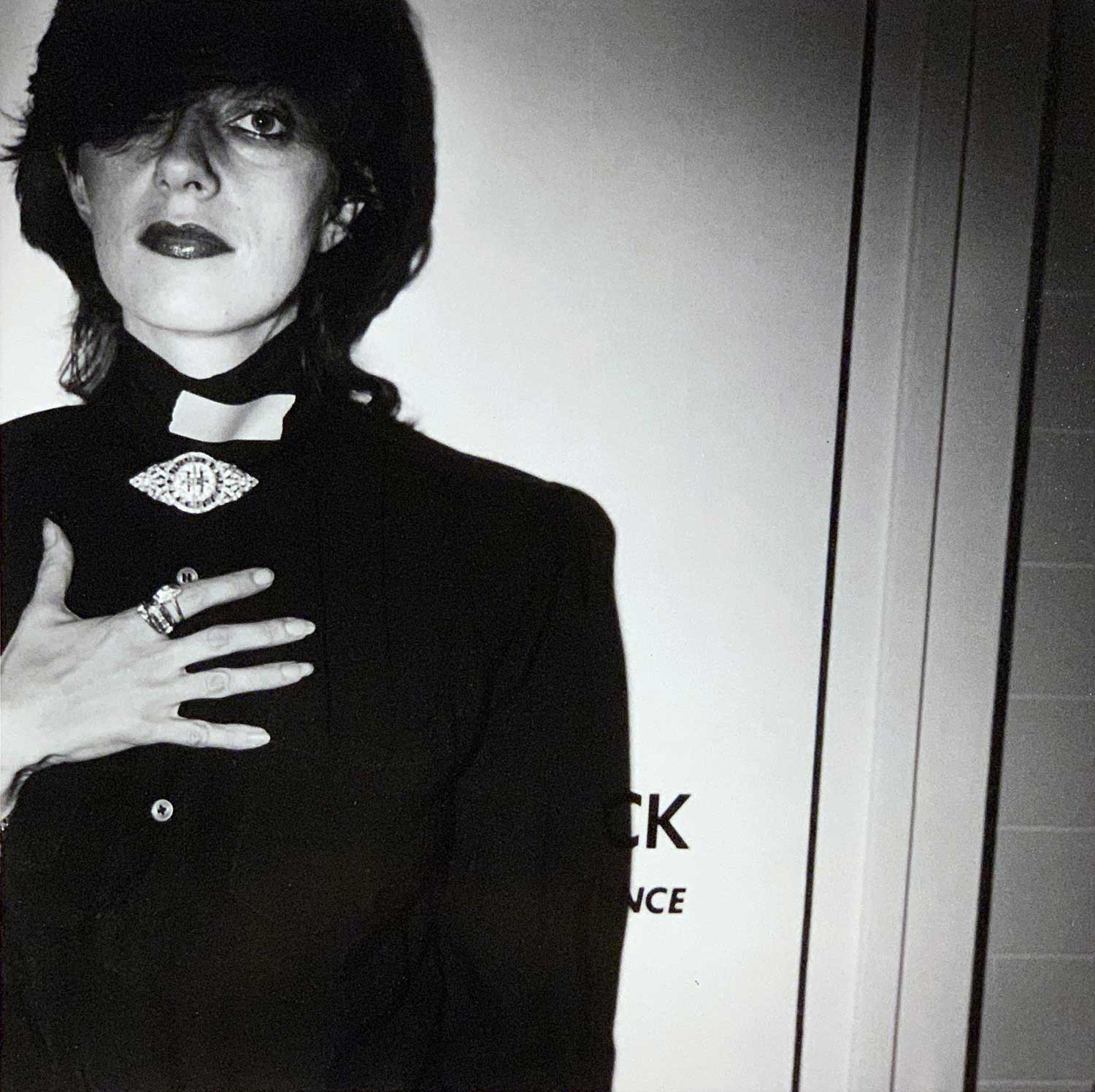

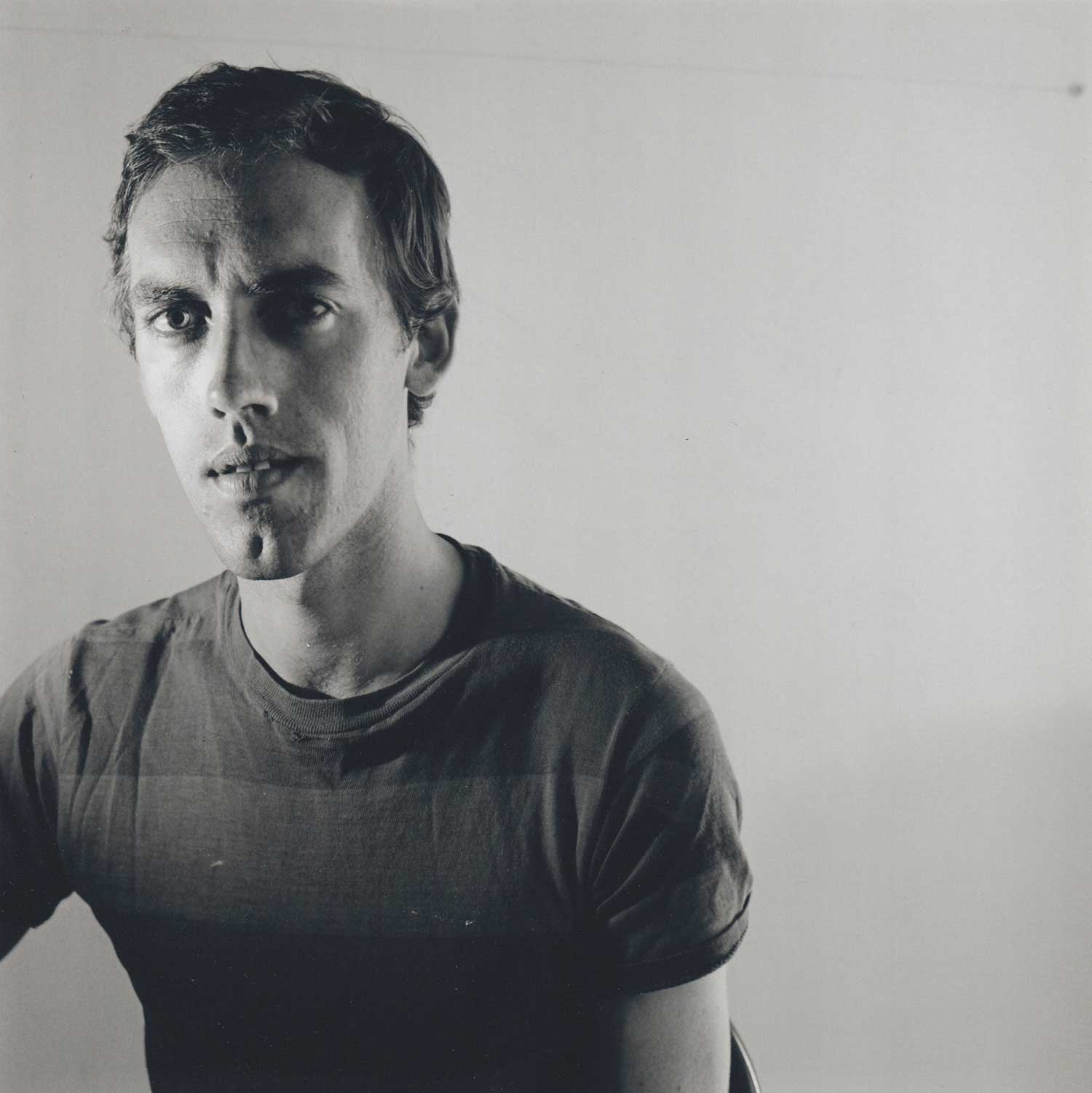

Gracie Mansion herself shows up in two photographs, taken at her show of Stephen Lack’s paintings, either peeking from behind her chic fringe of hair or topless and charismatically flexing her bicep. “Tim was my best friend,” she told me. “So it felt like a collaboration.” Lack himself shows up in another work, eyes ablaze and hands holding his head as buildings twist behind him. In a pair of landscapes of the infamous gay Valhalla, Pier 47, buildings collapse as if felled by the force of a vibrant Keith Haring piece poking through a corner, or another by David Wojnarowicz—who glares at the viewer in perhaps the show’s most astonishing photograph, sitting in a T-shirt in two-thirds of the frame and taking up the viewer’s entire field of vision.

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

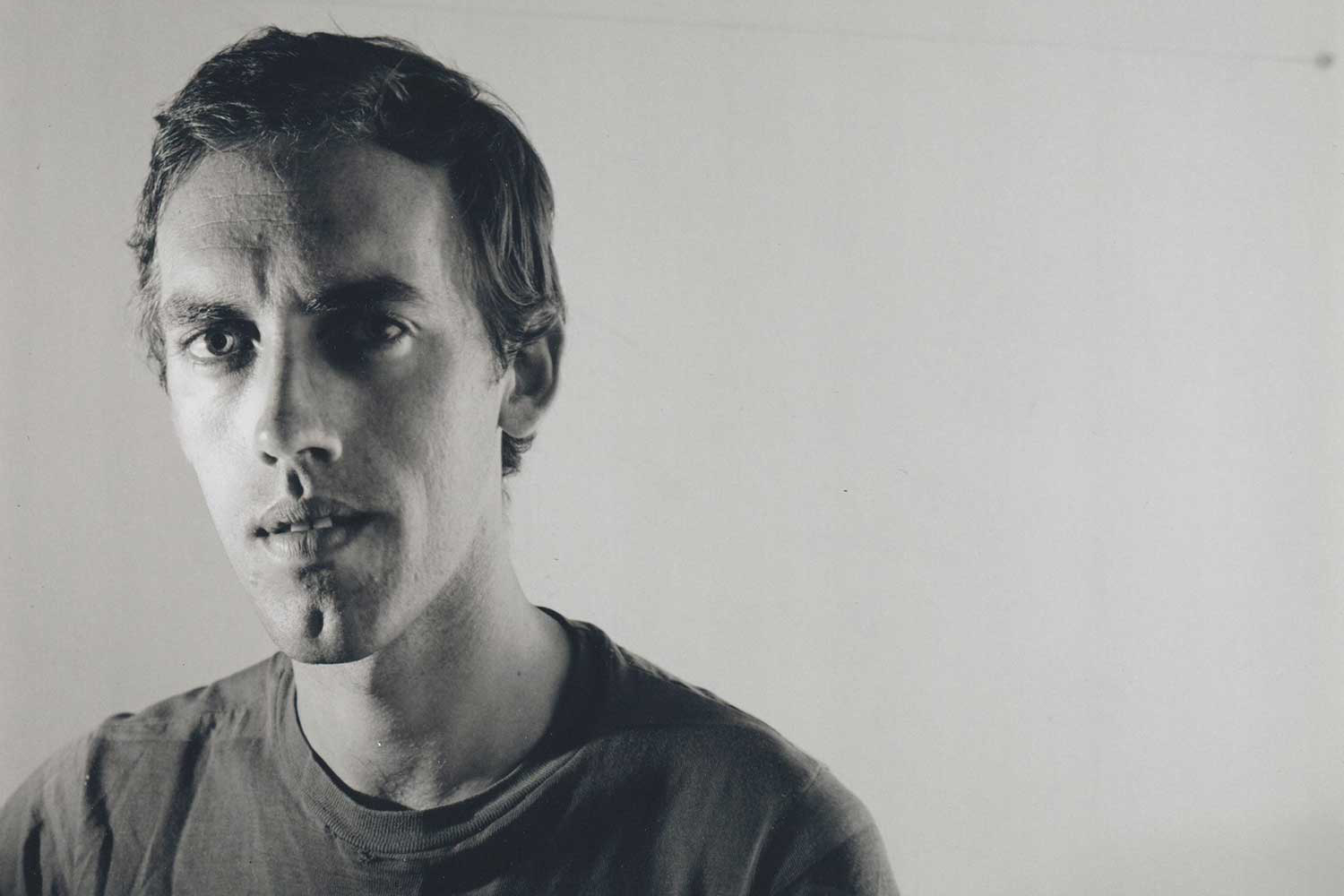

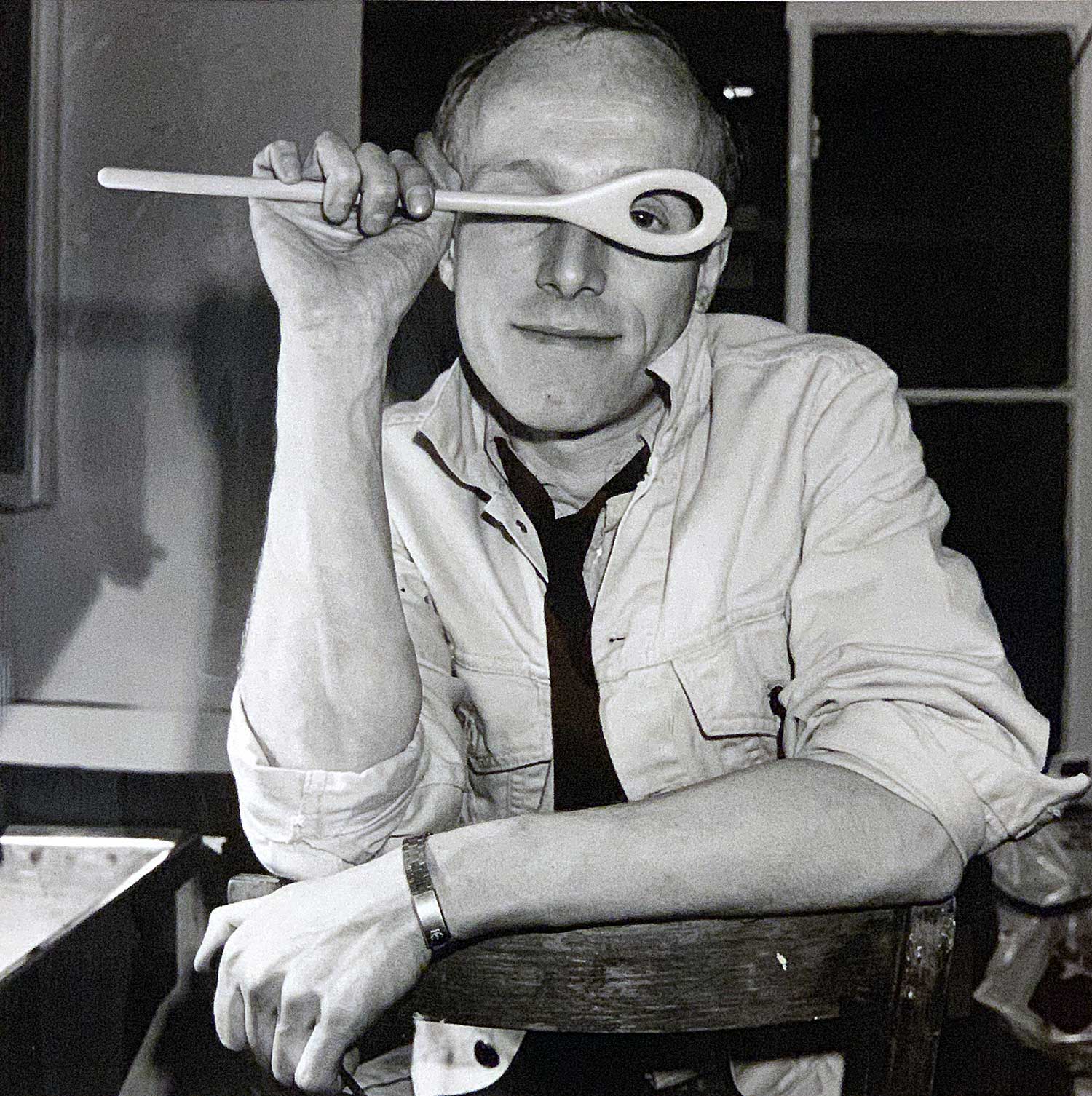

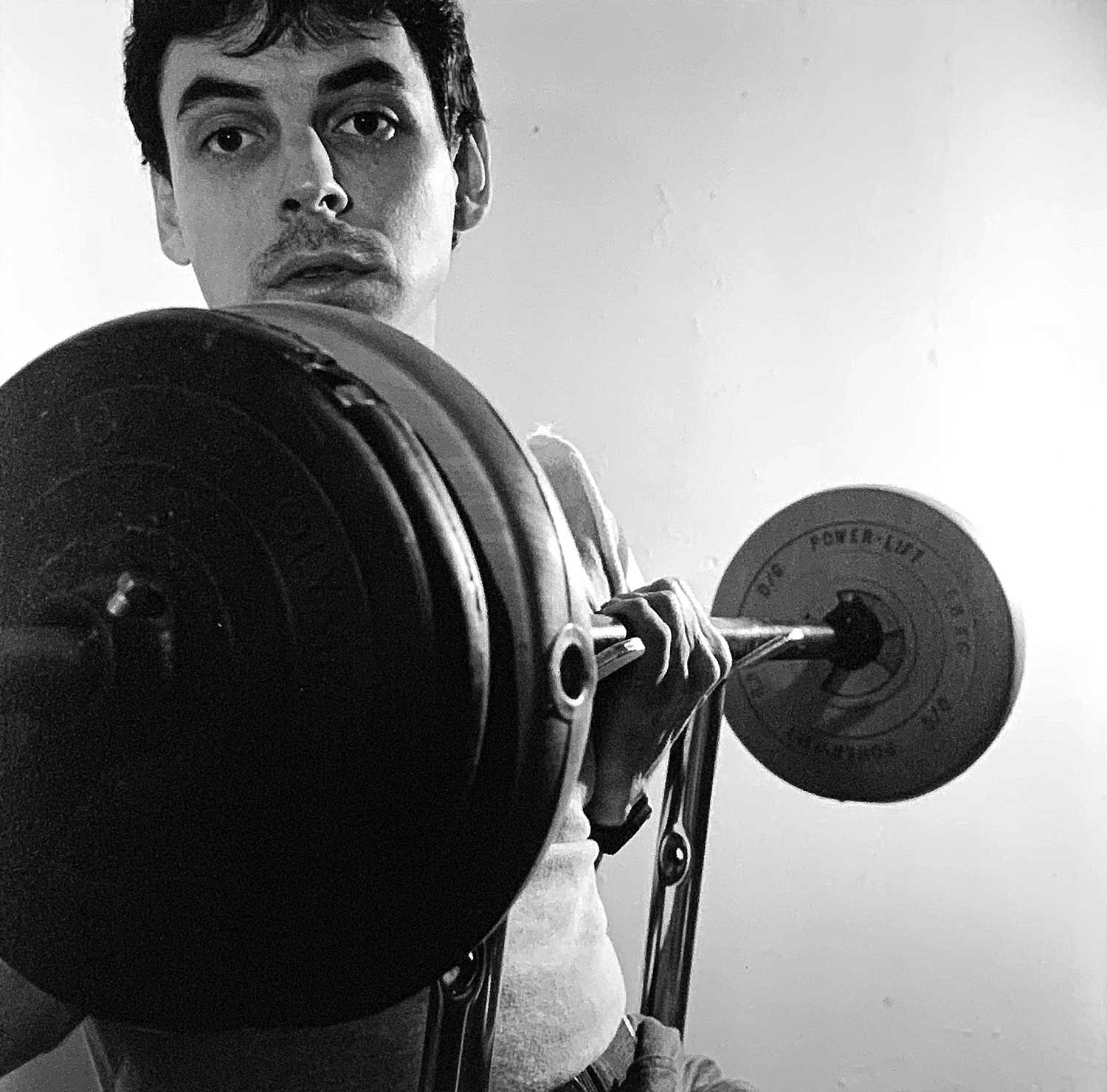

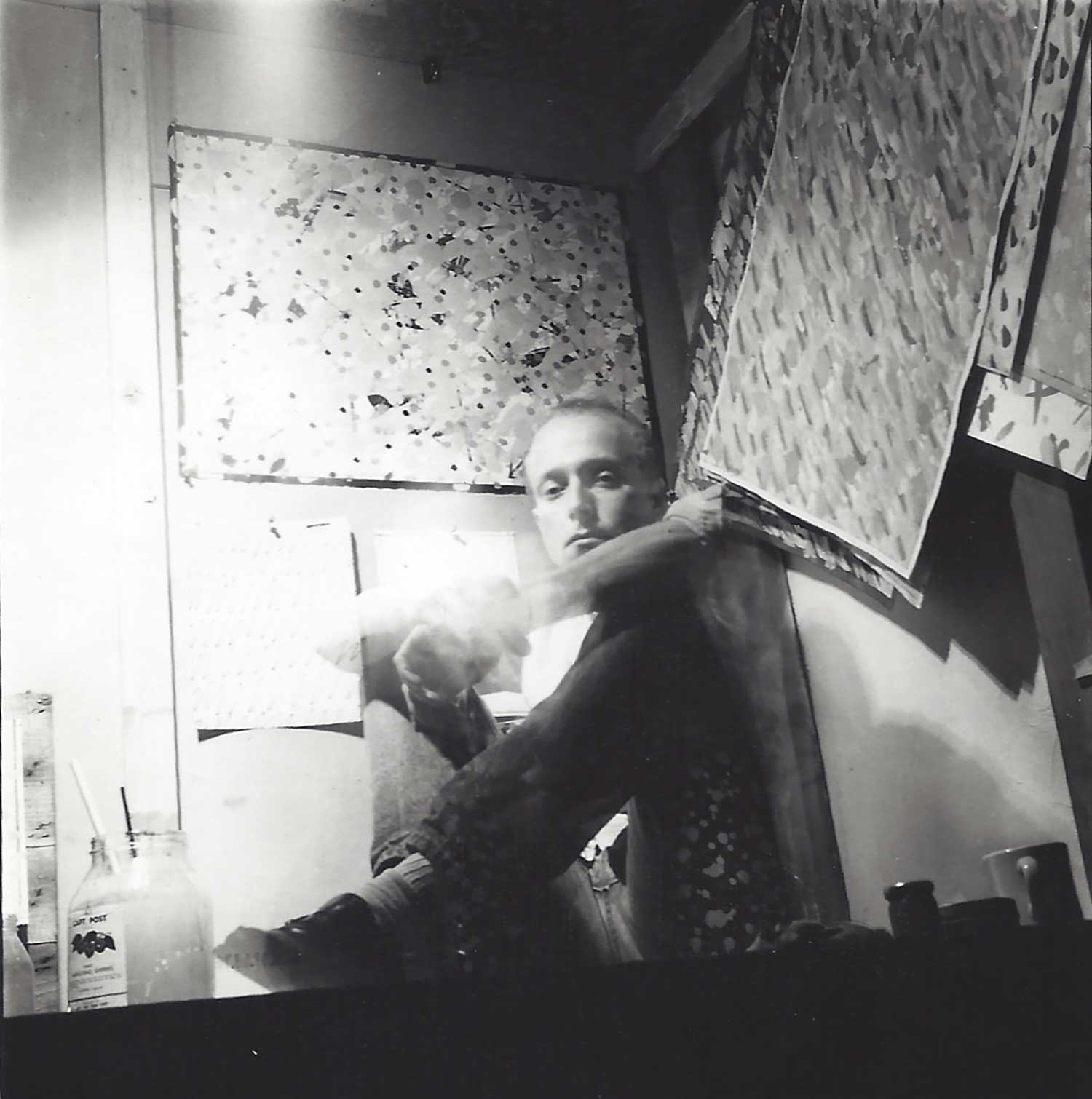

A couple of self-portraits capture Greathouse’s evident charm, whether serving the “clone” look—white tank top, mustache, stern bedroom eyes—in a 1978 shot or hovering in a blur of his own paintings a few years later. In 1983, he peeked through the hole of a wooden spoon and gave a little smile: I’ve never seen a photograph I’d more like to hug. Albeit, a first draft for a much-needed history of Greathouse and his warmhearted work, will hopefully nudge others who gathered in bathroom parties back then to go through their own file cabinets and see what else might remain.

Tim Greathouse: Albeit is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York, through February 29, 2020.