Tyler Mitchell’s Love for a Common Way of Life

By showing Black life as leisure, repose, and outdoor play, Mitchell expands our visual vocabulary of race and space.

“In nature, nothing is perfect. . . . Trees can be contorted, bent in weird ways, and they’re still beautiful.”

—Alice Walker

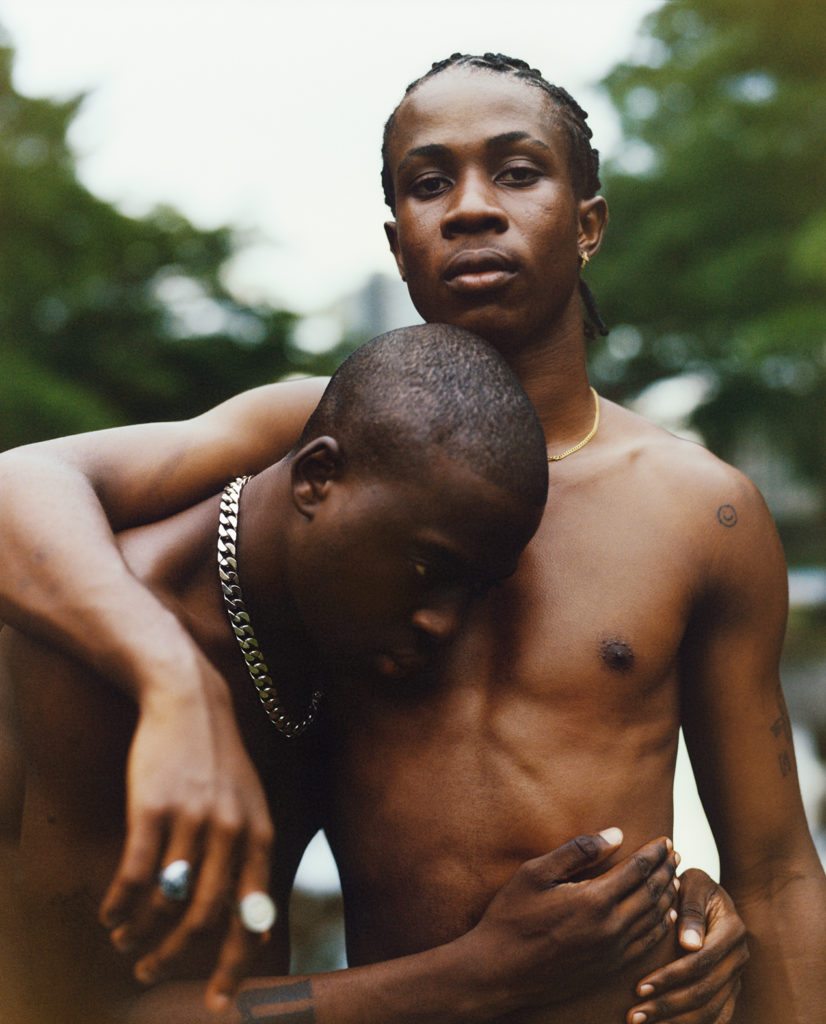

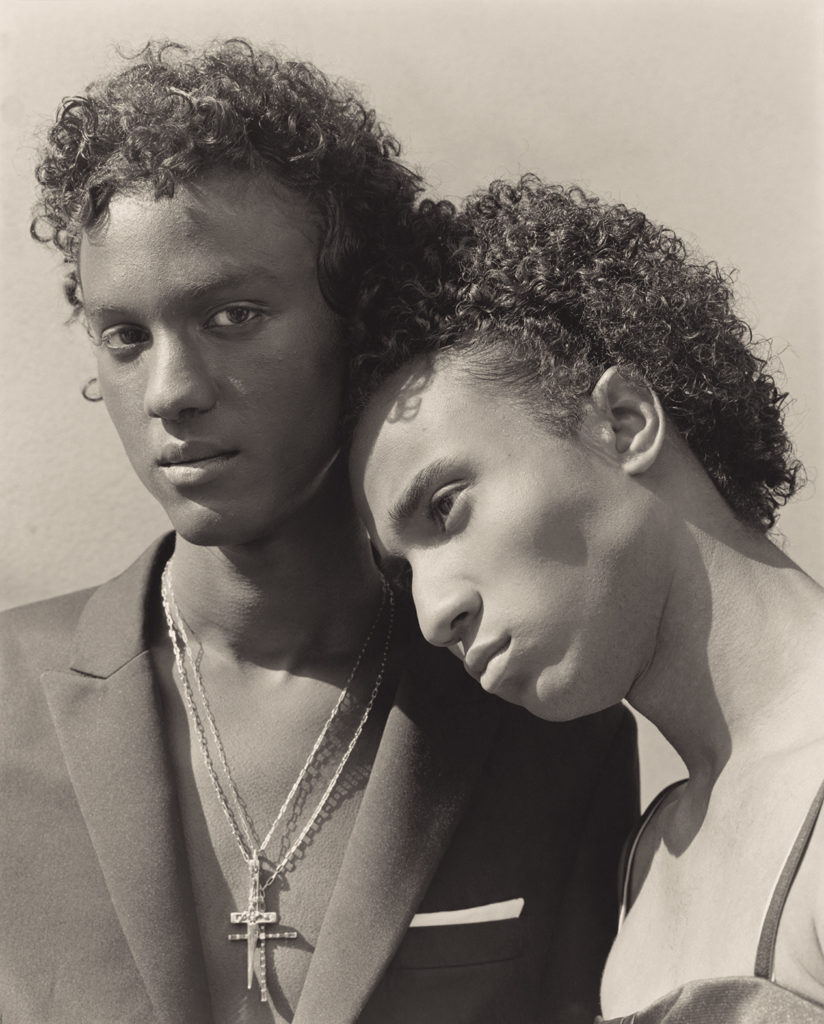

Two bare-chested young Black men on playground swings. Staring slightly down at the camera, the first young man, with twisted hair and striped boxers peeking out of his jeans, clasps the swing’s chains. Next to him, another young man, swinging in his ripped denim, with his eyes closed. His hands grab the chains in preparation for flight or, perhaps, a return to rest.

In Tyler Mitchell’s photobook I Can Make You Feel Good (2020), a debut monograph based on his first solo exhibition at Foam, in Amsterdam, in 2019, and at the International Center of Photography, in New York, in 2020, the depiction of these young men, partly naturally lit and in leisure themes, is in many ways a definitive aspect of his aesthetic.

Recently Mitchell has photographed a wide range of Black subjects, from the hip-hop artist Vince Staples to skaters in Havana, to take on an even more ambitious project: Black utopia. “People say utopia is never achievable,” he states in the foreword to his book, “but I love photography’s possibility of allowing me to dream and make that dream become very real.”

The result: young Black men in bright blue jeans, with dark brown to even deeper and richer brown skin tones, taking center stage with a beauty so brilliantly lit by the sun and caught by Mitchell’s eye that the allée of trees behind them all but disappears. Their freeness is intriguing, mainly because it depends on their being outside, making the outdoor backdrop relevant for what is there and what is not. Absent are those racial tragedies that inform my seeing and exist just beyond the photograph’s frame. Rekia Boyd: shot in the head by a white off -duty police officer in Chicago’s Douglas Park in 2012. Tamir Rice: shot in the chest by a white police officer at a Cleveland playground in 2014. Walter Scott: shot in the back while fleeing a white police officer in a North Charleston park in 2015. Among those calamities and, of course, our more recent ones, Mitchell’s insistence on seeing Black people at peace and in play in public is a profoundly radical act.

In this moment of Black Lives Matter, Mitchell’s films and photographs provide counternarratives to those viral recordings, such as Darnella Frazier’s ten-minute video of George Floyd’s murder. But, as his work reminds us of the long history of racism in the United States, it also reveals an alternative. “The African-American ties to this land, unfairly seized from Indigenous people, are ugly and thick,” the historian Tiya Miles wrote in her 2019 New York Times essay on race and environmental justice. “But even in that long, dark tunnel of suffering, African-Americans recognized the capacity of nature to function as a resource—better still, an ally—in the fight for physical and psychological freedom.”

By showing us Black life as leisure, as repose, as outdoor play, Mitchell continually expands our visual vocabulary of race and space. I search his photographs for more geographic clues. Yet with those young men on the swings, their hairstyles and sartorial details convey only their nowness, not their place. The playground swings tell me something, but not enough. The trees, blurred into a lush mise-en-scène, could be a field, a forest, a farm, or a park. Each potential site has its own racial history, each choice would pose different types of threats for their swinging Black bodies. But in Mitchell’s freedom dreaming, these trees are not used for harm.

With their heads and chests arched forward, their loosely picked-out coils, and the way their jeans hang just so, his Black male models use the trees as a canvas onto which they, not us, can project the artist’s versions of themselves far into the future.

When Mitchell and I spoke on Zoom this August, a week after his book’s release, he was in London, while I chatted from Newark. He was backdropped by potted plants and arching trees that transformed the backyard patio where he sat into a small garden. Knowing that he spent the majority of New York’s pandemic lockdown in his Brooklyn apartment, I thought that any attempt he made to establish a temporary life in another country, and in fresh air, was well-earned.

And yet nature has a way of interrupting our best intentions. Not long into our conversation, a bee started circling him, eventually disturbing him, so that he had to go back inside. Looking back, Mitchell’s desire to remain outside was not just happenstance but fundamental to his autobiography, his aesthetic, and his redefining of Black life.

Two young Black men sitting on the grass. The one at left in a rose T-shirt, eyes down, smile bright. Beside him, his friend, or lover, cousin, or brother, an ambiguity suggested by the unknowable meaning of their near touch. What is clear are their smiles. The young man in the unbuttoned, blue shirt, revealing his bare chest, is mid-turn, hands clutched underneath the ball about to drop. Another man, in a pink, blue, and white striped shirt, zips by them. We see only his back and legs in stride, and his locks swaying, trailed by his matching kite.

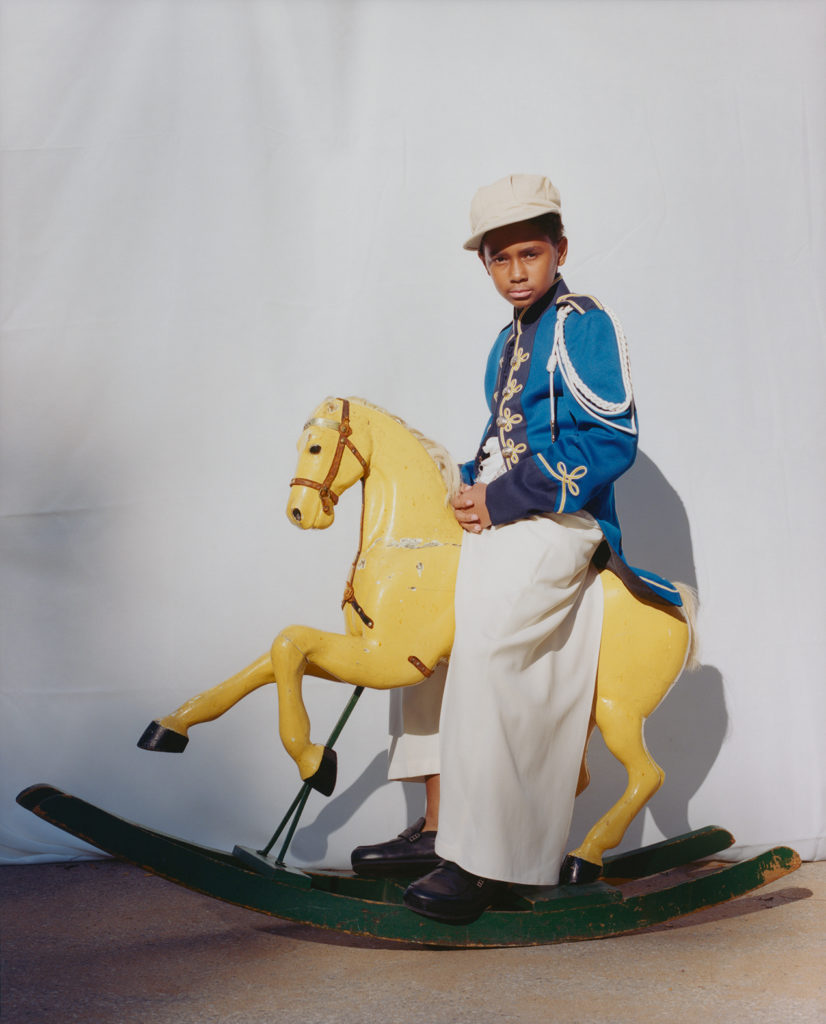

Another image. A young Black boy, dressed up in a royal-blue military jacket, his dusty-brown skin quieting the gold braids and buttons adorning the uniform. The white sheet that hangs as a backdrop is reminiscent of Mitchell’s famed September 2018 cover for Vogue, when, at twenty-three years old, he became the first African American artist to shoot the magazine’s cover in its 125-year history, photographing a minimally made-up Beyoncé outside, with only white sheets as backdrops and props. While his clothing and fancy rocking chair intimate an aristocratic flair, the white sheet and outdoor pavement indicate everydayness. Here, these stylized juxtapositions work together to convey Mitchell’s refusal of spatial and sartorial hierarchies.

Inspired by Spike Jonze’s skate videos, Mitchell, in his early work, used his friends and fellow skateboarders as subjects. He documented their aerials and slide tricks with a digital SLR Canon, whose flip switch enabled him to toggle between photography and video. As a result, play was inseparable from the visual languages he was teaching himself. “Of course, there’s the surface level cool and rebel spirit about skateboarding,” Mitchell told Vogue in 2018, “but the thing that makes skaters like artists runs deeper than that: It’s not a sport that’s built on competition, it’s one that thrives on community.”

Much has been made about how Jonze’s work, along with the casual snapshot style of Ryan McGinley and the gritty youth-culture focus of Larry Clark, has informed Mitchell’s approach. In his own narration, he mentions them, but he also speaks about how Tumblr not only introduced him to creative photography but helped to shape an egalitarian aesthetic. “I think the link for me to Tumblr growing up was a lot more significant than even I realize, in a way,” he tells me. “There, images come to you in a swarm of decontextualization. One thing is next to the next, and they might have nothing to do with one another, but your mind creates a link between two images.” He goes on, “It could be a Rococo painting next to a highly conceptual image of a performance artist. And then it could be next to a very chic modern interior.”

After reading as much as I could about Mitchell, I noticed one crucial aspect of his life that he returns to but that most writers overlook: the role that growing up in the Black South has played in birthing his sense of place and play. “Atlanta, and being from Georgia, frames how I approach my own autobiographical ideas of utopia,” he muses. “Being middle-class, having leisure time in the summers, gave me the opportunity to think about it as a site of utopia, or a potential utopia.” Mitchell notes his aesthetic came out of “that free time and those memories of playing in fields or in parks in Georgia.”

In other words, Mitchell’s Black utopianism comes from his nondifferentiation. Taking Tumblr, with its nonhierarchical format, as a political and photographic practice, Mitchell not only toggles between visual mediums but normalizes the celebrity and exalts the everyday citizen. “One of the biggest things I’ve been reflecting on these days is the whole idea of the hierarchy between photographer and subject. I have a tool and a camera that I’m using to convey something or someone,” Mitchell says to me. “And inherent to photography, especially when you think of it historically, is a strong hierarchy, where the photographer is the one with all the power, the one who is seeing. And the person being seen has almost no power. So, for me personally as a photographer, I ask myself, ‘What are the things I can do to lessen these inherent hierarchies in the photography-shoot structure of seeing and being seen?’”

At the same time, his radical flattening of divisions is also a reflection of his expansive worldview, much like the poetry and novels of his fellow Georgia native Alice Walker that seek to celebrate and canonize the diversity innate to nature. “When you see an aerial shot of Atlanta, which I’m really interested in, it’s full of trees,” he says about growing up right outside Atlanta, a city with more green space per resident than any other U.S. metropolis. “You’re in a city whose skyline is really weird. That’s what I grew up around, being surrounded by nature constantly, and near a city with a Black core. A strong Black inner core.”

All works by Tyler Mitchell © the artist

Another image. In the book it is fixed, but it is an excerpt from his 2019 film Chasing Pink, Found Red. Here, young Black men and women, eyes closed, bodies dressed in whites, khakis, and browns, nearly touch as they lie together on a red-and-white-checkered picnic blanket. Their stillness recalls the 2015 die-in protests in the early years of Black Lives Matter; their stillness also insists that they rest among each other as a form of self-care and self-protection. While Mitchell’s extolling of Black leisure might be new to some, it is familiar to those of us who have turned to play as both a testament to our humanity and a form of resistance in a world in which our Black lives still don’t matter.

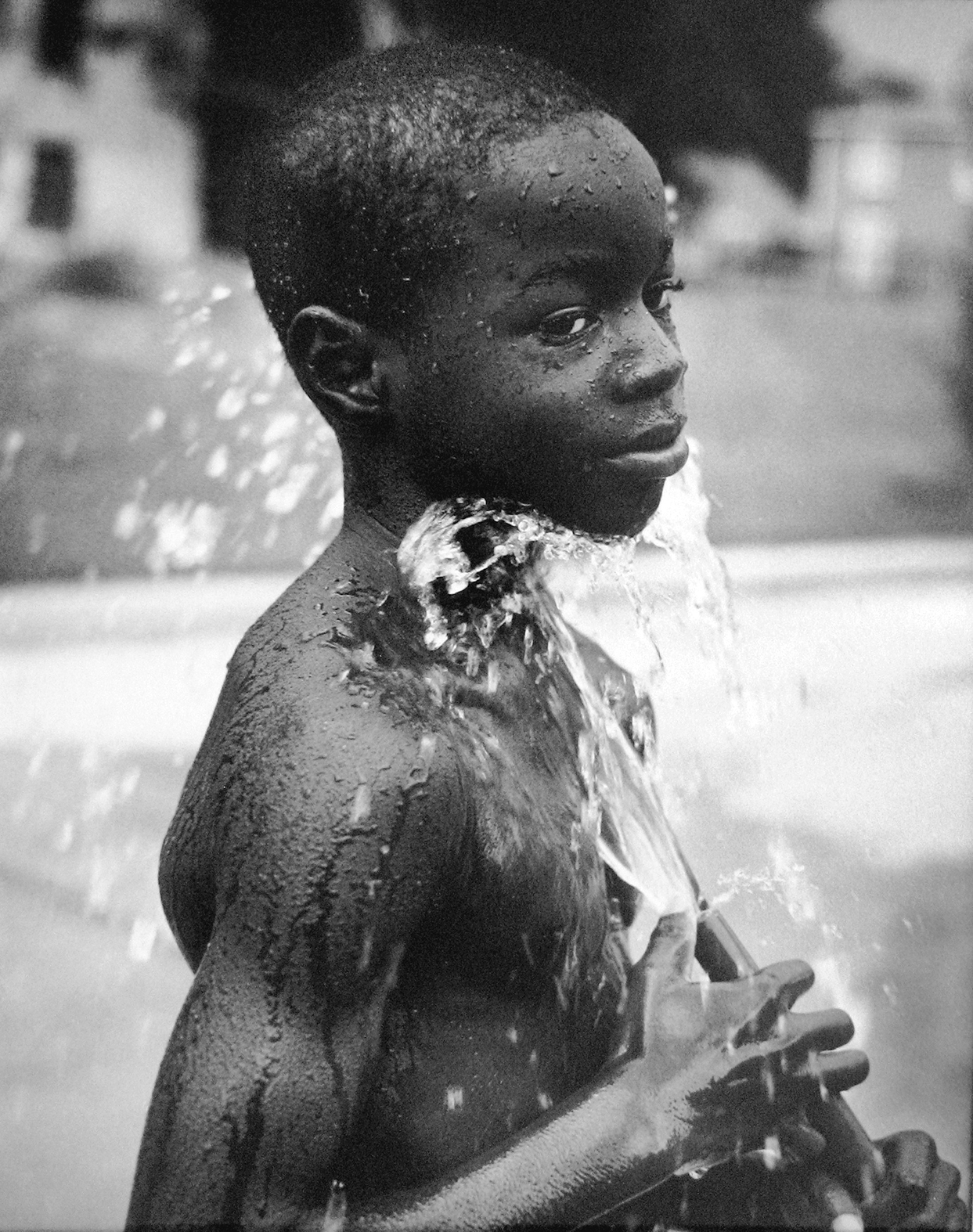

In this way, Mitchell is a student, as he quite earnestly told me, of Earlie Hudnall Jr., a Mississippi-born African American photographer who has spent the majority of his career documenting Houston’s historically Black Third Ward neighborhood. Hudnall’s black-and-white photograph Flipping Boy, 4th Ward (1983), featuring a young Black boy, mid-backflip, in the middle of a Houston street, anticipated Mitchell’s own skateboard montages and Hula-Hoop close-ups. Hudnall’s Cooling Down, 3rd Ward (1997) of a little Black boy gleefully splashing himself with a hose conjures up the joy seen in Mitchell’s images of young Black men flying kites or on swings. And, finally, his Rascals, 3rd Ward (1991), depicting a group of little Black boys proudly standing in front of their bikes, made four years before Mitchell was born, reminds me of the pride of Mitchell’s own regal portrait of the young boy on a play horse.

Courtesy the artist and PDNB Gallery, Dallas

In a statement about his work, Hudnall said that, in addition to his father, who was an amateur photographer, it was his grandmother’s use of a photo-album to record their community’s history that inspired his own interest in documenting quotidian moments rarely seen outside the community. “The love for this common way of life and the memories of those times,” Hudnall recalled, “provided me with the inspiration to become a photographer, just as Grandmother used the photo-album and the family Bible.” Crisscrossing fashion, art photography, and avant-garde filmmaking, Mitchell offers us a Black utopia in which the couture and the common sit next to each other, and in which Black people in London, Brooklyn, Atlanta, Los Angeles, and throughout the African diaspora find one another, as relief and community. And therein lies Mitchell’s gift and genius, to reimagine our world with the possibilities and agency of Black life. “My images are made all over the place,” Mitchell says. “The subjects and the geography just support this aesthetic universe of a utopia. It’s not meant to be pinned down.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” Winter 2020, under the title “Tyler Mitchell: Love for a Common Way of Life.” Read more from the issue, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.