Valérie Belin's Uncanny Visions

The French artist’s most recent work explores the dark side of pop culture and beauty.

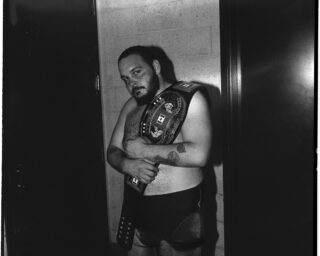

Valérie Belin, Golden Girl, 2016, from All Star

© and courtesy the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York and Zurich

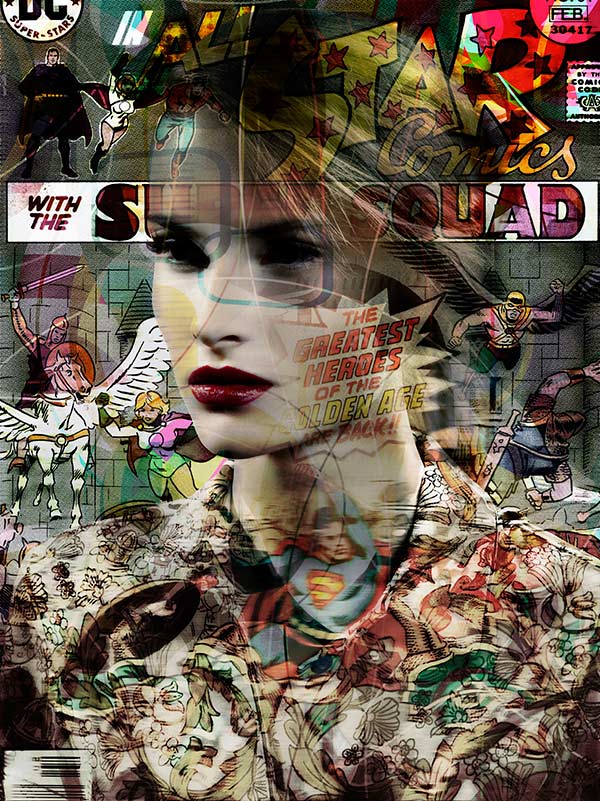

In Valérie Belin’s latest series, All Star (2016), currently on view at Edwynn Houk Gallery in New York, Belin places the faces of pale, idealized women against a background of digitally collaged, 1950s comic strips. The unidentified, unnamed models appear passive, almost forlorn, with eyes cast down or obscured by shadow. Rife with scenes of chaos and destruction, the composition and graphic quality of the images evokes nightmarish magazine covers, but each print stands about five-and-a-half feet tall—miniature billboards in scale. How confusing, how chaotic, how layered—and yet, how consumable.

Born in France in 1964, the Paris-based Belin’s work centers on questions of surface, artifice, consumerism, and the indexical nature of images—that is, the often fraught way that photographs relate to the object they depict. She said she has long been haunted by what she refers to as “the stereotype,” Belin told me recently in an interview by email, and how people either conform to or reject norms of gender and appearance—for example, bodybuilders both male and female, transgender women, and Moroccan brides imprisoned in ceremonial garb. “My subjects all have cliché status,” she explained.

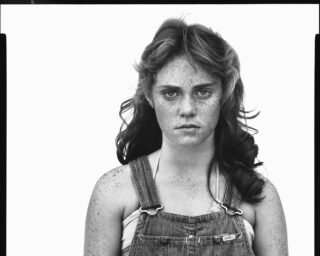

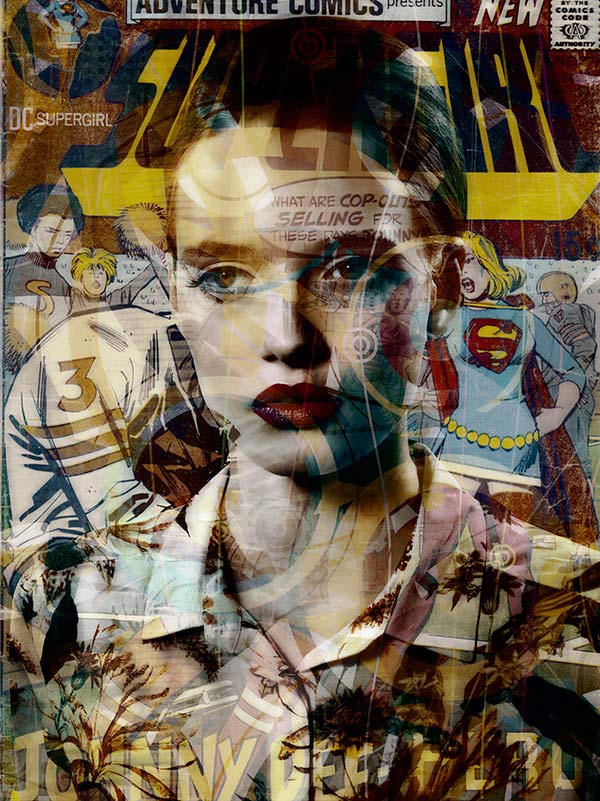

Valérie Belin, Super Girl, 2016, from All Star

© and courtesy the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York and Zurich

This straightforward solo exhibition gleams in Edwynn Houk’s tony Fifth Avenue gallery. One of the more striking pictures, Super Girl (2016), is typical of the series. Belin has placed the model in accordance with the “two-thirds” rule of photography, a cliché of composition. Alluding to her previous series, Belin burned the shadows of flowers into the model’s white collared shirt. Around her face, cheerleaders pump yellow pompoms as football players take the field, and a Supergirl figure shows a sliver of her thighs between her red boots and blue minidress as she shouts into the model’s ear. It’s not clear what she’s shouting. But her diminutive, almost oxymoronic title, reminds me that, during the 2016 Olympics, world-class athletes still had to demand that male commentators refer to them as women, not girls.

Belin explicitly deals with the feminine, in both style and subject. Presaging the layering critique of her recent work, Black Eyed Susan (2010–13), situates portraits of women styled with ’50s-inspired hair and makeup against floral backgrounds. Belin says she sees the battle for feminism as already won by an older generation, and she doesn’t consider her work to be overtly political. At the same time, she knows the art world doesn’t treat women equally. Asked how her work relates to other female-identifying artists who have worked with photography and abstraction, such as Anna Atkins, she replied: “Parity does not exist. One could even say that in many cases the work of a woman artist is taken seriously only if it touches on the female condition. The theme legitimizes the work’s artistic status.”

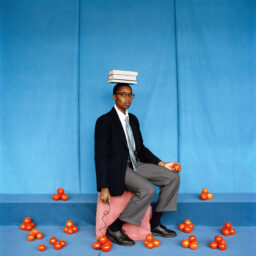

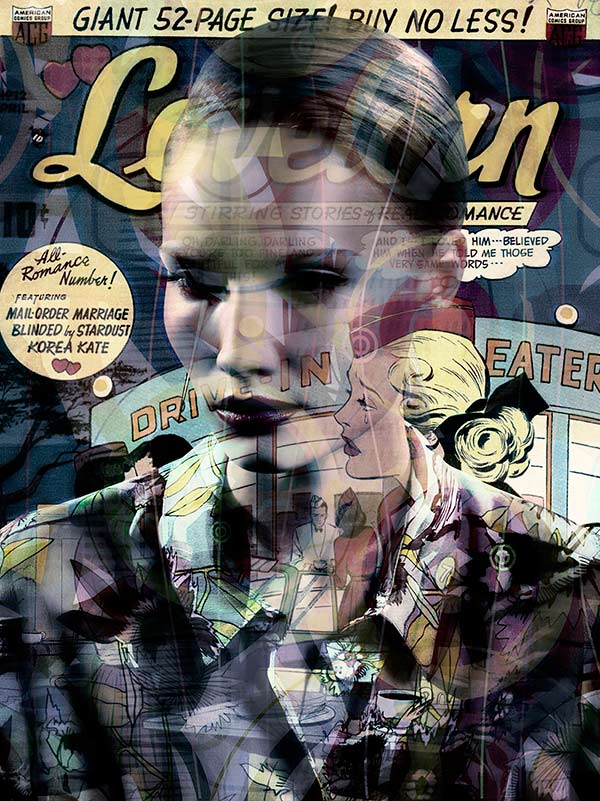

Valérie Belin, Confessions of the Lovelorn, 2016, from All Star

© and courtesy the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York and Zurich

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the All Star series is that all of the models look so alike. Yet this is intentional. Referring to a 2003 series titled Mannequins, Belin notes, “A very recognizable beauty is dissolved into an empty plasticity.” The eerie similarities between Belin’s portraits of mannequins, and the ways in which Western culture routinely objectifies women’s bodies, are striking. When Belin depicts “real” women as digitally manipulated specters, however, it’s difficult to separate them from the similar images so common in advertising. In her influential book, The Beauty Myth (1990), Naomi Wolf argues that images of female beauty are used against women’s advancement. Instead of being presented with pictures of women who vary in weight, age, race, ability, and class, we see “a dissemination of millions of images of the current ideal.” In 2017, thanks to the Internet and digital media, make that billions. In using these idealized images of women, is Belin making a much-needed critique, or feeding the machine?

Valérie Belin: All Star is on view at Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York, through March 4, 2017.