A Visual Record of Black Lives, Four Decades After Emancipation

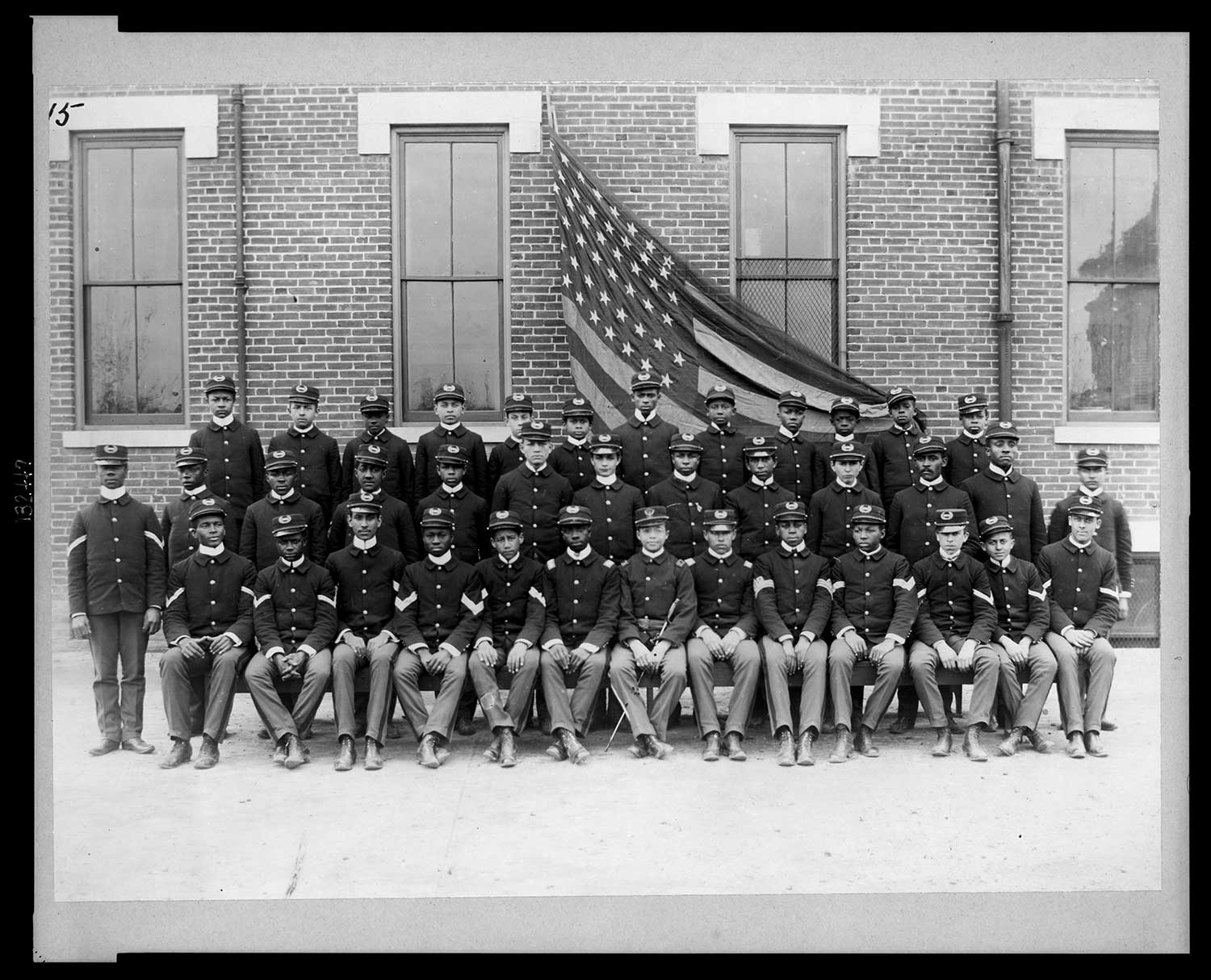

Cadets at Haines Normal and Industrial Institute, Augusta, Georgia, from The Exhibit of American Negroes, 1900

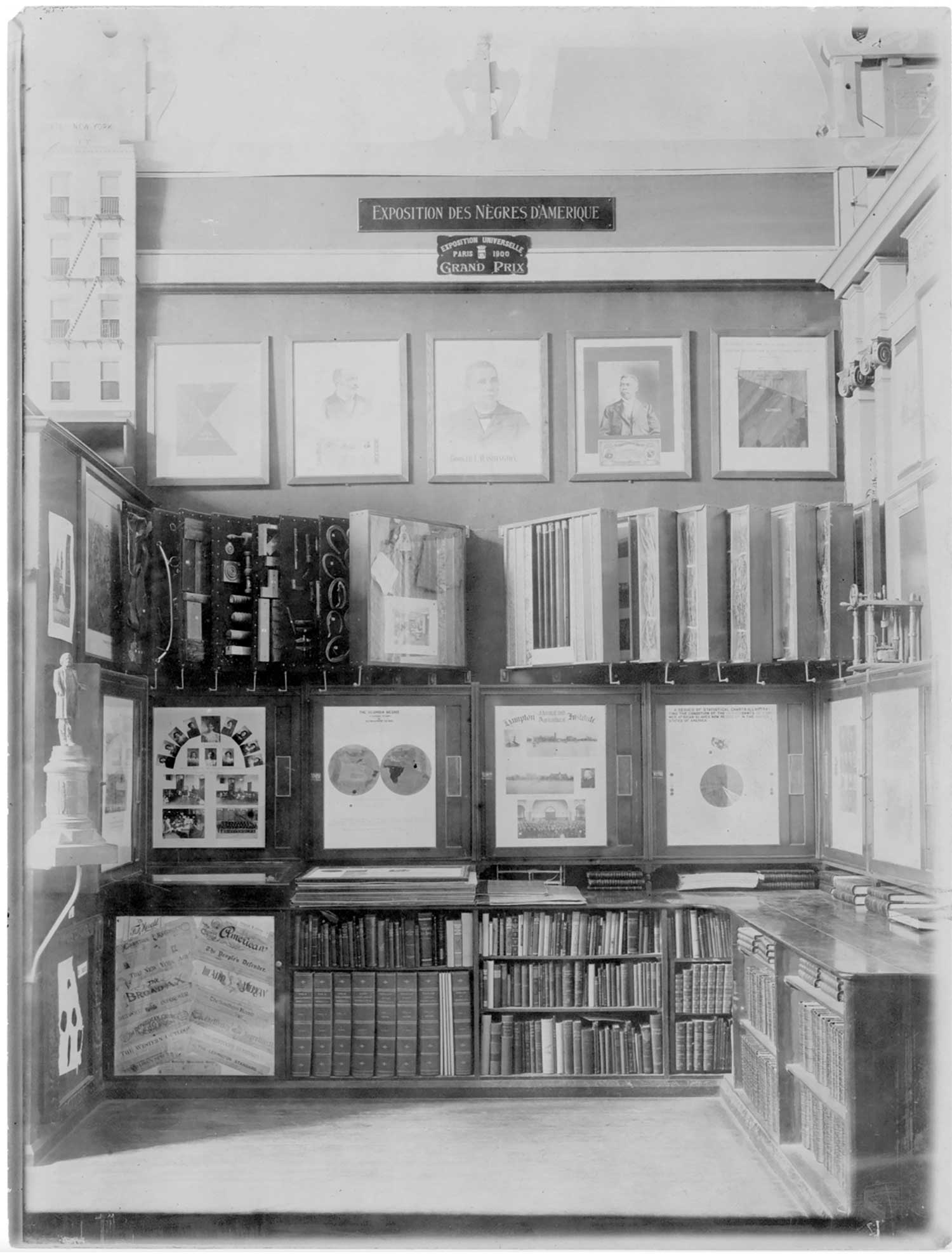

In 1900, partway through the official planning for The Exhibit of American Negroes at the Paris Exposition, photographer Harry Shepherd was kicked off of the project. Shepherd was a successful African American studio-owner from Minnesota, and for the fair’s American Pavilion, he had photographed students at Black colleges in the South. He showed particular compassion for young people trying to figure out what kinds of members of society they might become, as Black Codes and Jim Crow laws increasingly encroached on their prospects. But these photographs were not the cause of controversy. According to the Afro-American Advance, Shepherd was dismissed from the project for preaching “anarchy” in the South and advising “the Negroes to combine against the United States in the event of war with foreign powers.”

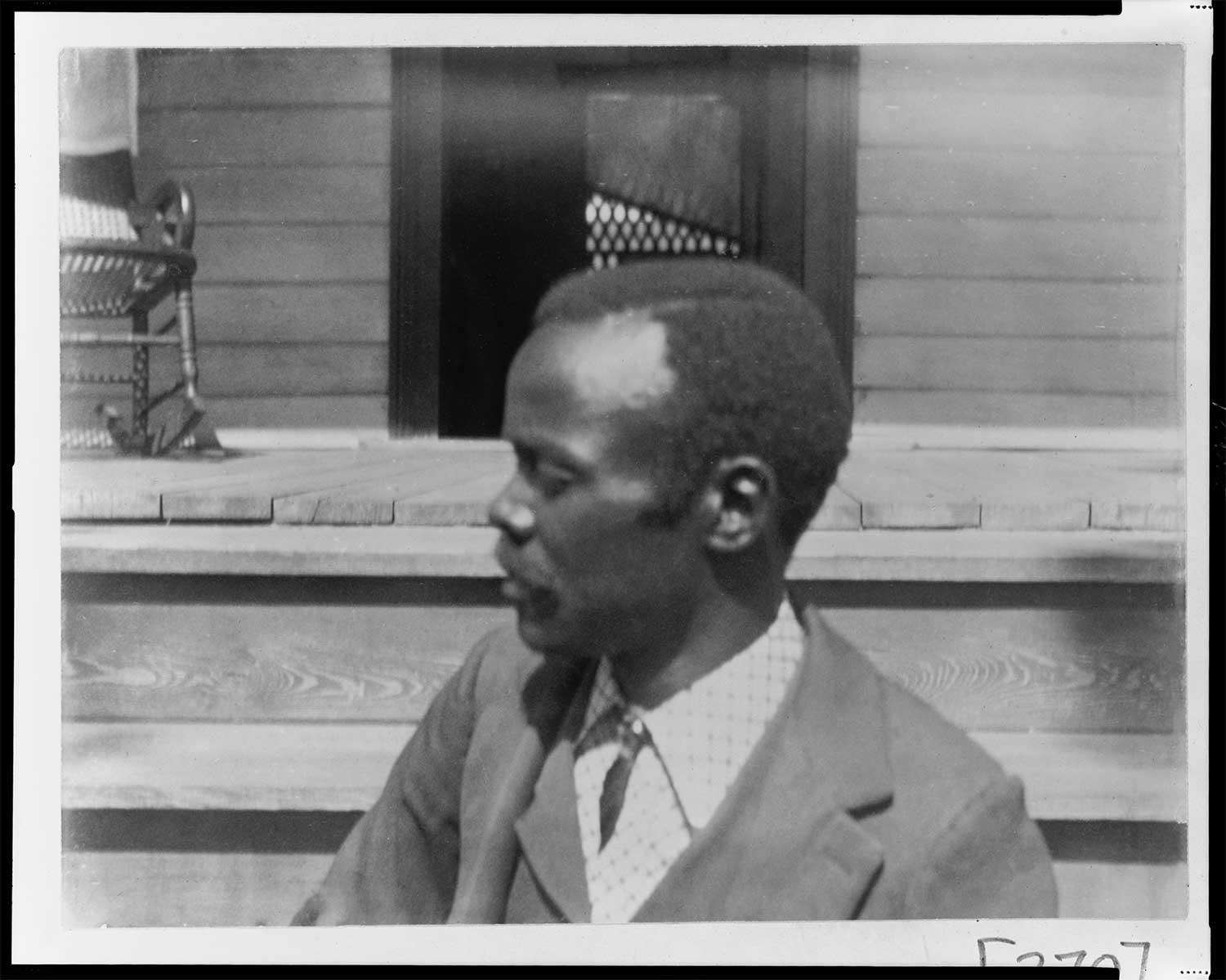

Man seen in profile, from The Exhibit of American Negroes, 1900

Shepherd is a pretty fleeting character in the history of the American Negro exhibition, which was co-organized by W. E. B. Du Bois. The first and only time I came across Shepherd in the scholarly literature on the exhibition was in Deborah Willis’s and David Levering Lewis’s seminal work on the subject, A Small Nation of People: W. E. B. Du Bois and African American Portraits of Progress (2005). He remains a footnote contributor to the exhibition’s visual archive. But Shepherd rushed to my mind while I was studying visual pairs of photographs and infographics in the book Black Lives 1900: W. E. B. Du Bois at the Paris Exposition (2019), edited by Julian Rothenstein.

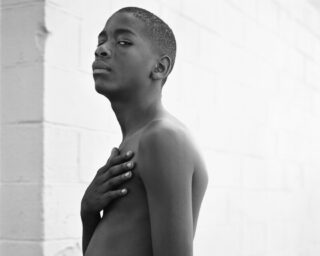

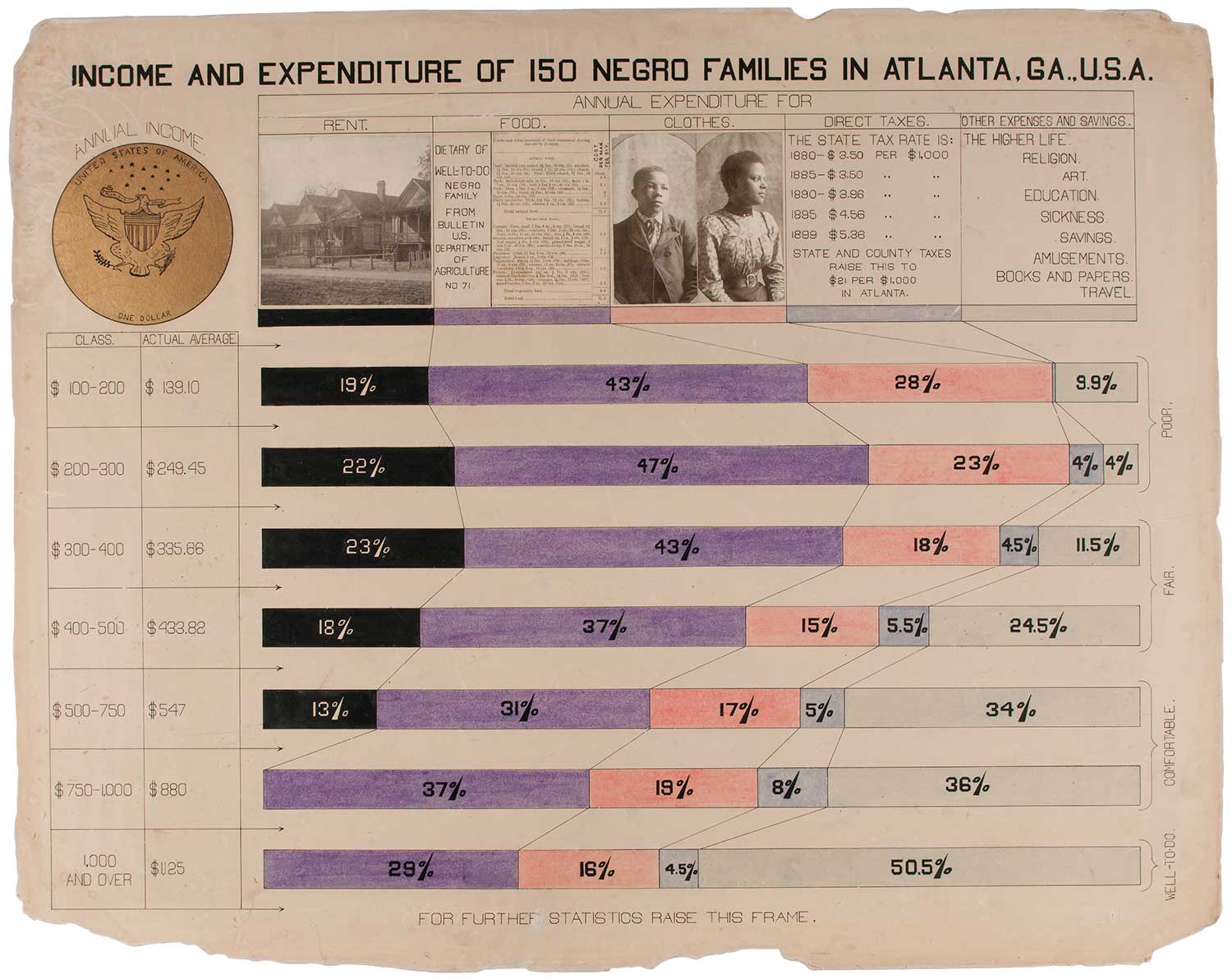

On one page in the book, cadets pose in rows for a group portrait in front of an American flag at the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in Augusta, Georgia. They appear so upright and stern that this group of young boys looks almost like men. Their fidgeting, uncertain hands and curious faces give away their performance. On the opposing page, an infographic depicts the “proportion of Negroes in the total population of the United States” as literal small nations within a nation, to use Du Bois’s phrase. At the turn of the century, in the midst of wars, colonization, and a burgeoning twentieth-century Pan-African movement, these cadets stood at a crossroads. Where Shepherd proposed anarchy, Du Bois strategized an exhibition, placing Black students like these at the center of a global conversation on progress.

Infographic from The Exhibit of American Negroes, 1900

Du Bois originally displayed the photographs and infographics in the award-winning Paris exhibition separately: three thick albums of hundreds of photographs, a set of infographics on the “Georgia Negro,” and another set of infographics on “the Condition of the Descendants of Former African Slaves Now in Residence in the United States of America.” Each set offered discrete narratives and arguments. In Black Lives 1900, Rothenstein takes on the interpretative challenge of reading the photographs and the data visualizations together. This approach opens up the archive in some instances—working Shepherd and his politics back into the story—and overdetermines or flattens the archive in others.

In one spread, Rothenstein places a studio portrait of a young girl, with a light complexion and silky curls, looking at an open book above an image of three women and a man hoeing in what appears to be a hot field. Rothenstein pairs these photographs with an infographic that compares the number of Black people living in cites to those in rural areas and villages in 1890. The photographs not only mimic the explanatory function of the infographic, they make a more specific claim: to be urban is to comport oneself as pristine, contemplative, and youthful, to imagine a life in modern cities away from a feudal past. Rothenstein is likely gesturing toward Alain Locke’s canonical (and criticized) concept of the “New Negro,” which would take root among Black intellectuals and artists decades after The Exhibit of American Negroes. But without some kind of contextual nudge, the pairing risks reproducing Black archetypes rather than complicating them.

The Exhibit of American Negroes at the Paris Exposition, 1900

Black Lives 1900 celebrates the dynamism of the Paris exhibition’s visual archive, but the photographs and infographics might be better analyzed and interpreted when treated on their own terms. They each emerge from entirely different visual logics and concerns, and for Du Bois, the distinctions were critical. The photo albums he compiled included no captions, no markers; he instead arranged a visual record of Black living that could reference itself. The infographics presented numerical data as striking visual figures. Through modernist aesthetics, Du Bois made the statement that any competent study of Black Americans into the new century would need a new framework, a novel way of considering social scientific data. If the importance of the exhibition and its legacy relies on Du Bois’s meticulous attention to the visual in distinct ways, then maybe a dynamic, information-dense archive of this kind needs the spaciousness that a live exhibition affords. If not a new exhibition, then a more exhaustive scholarly catalogue.

The archive and this book are ultimately about Black lives as a subject of visual empirical study. Still, I’m itching to appreciate these photographs and the people in them as something other than figural data points, and the addition of the infographics only enhances that desire. While elegant, even the portraits feel quite lonely and impersonal. To be Black and aspirational at the turn of the century and on the world stage is to possibly feel isolated and scrutinized, even while being admired.

Young women, three-quarter length portrait, from The Exhibit of American Negroes, 1900

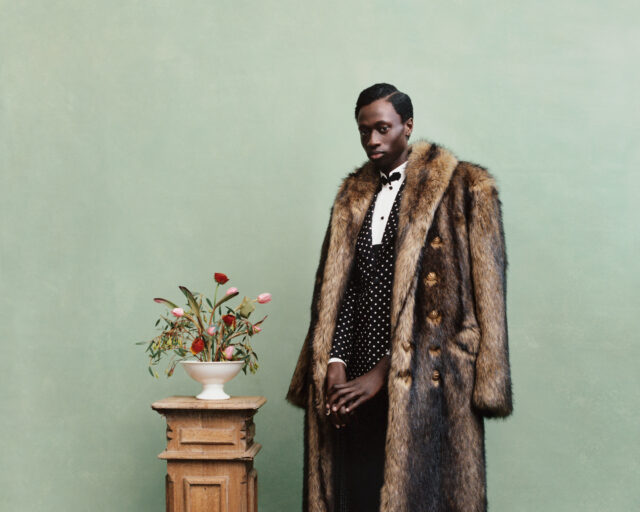

I did find one delightful moment of intimacy, a glimpse of Black sociality beyond the twin burdens of representation and exceptionalism. Two young women pose together in a three-quarter length studio portrait. Unlike all of the other group portraits in the book, these sitters touch, nearly embrace. One woman sits on the other’s lap, their hands clasped and resting on the former’s thigh. Their rings glitter; their gazes linger. The woman smiles up at her friend—or lover—this person is special to her. The caption does not identify sitters by name nor relation; the photographs were intended to be representative after all. But the touch between these two women, the warmth made and held between them, is entirely their own. This portrait—its tenderness, its intimacy—holds open the purpose at the heart of the project. That is, in Du Bois’s words, to picture Black lives honestly, “without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves.”

Black Lives 1900: W. E. B. Du Bois at the Paris Exposition was published by Redstone Press in October 2019. All images courtesy Redstone Press.