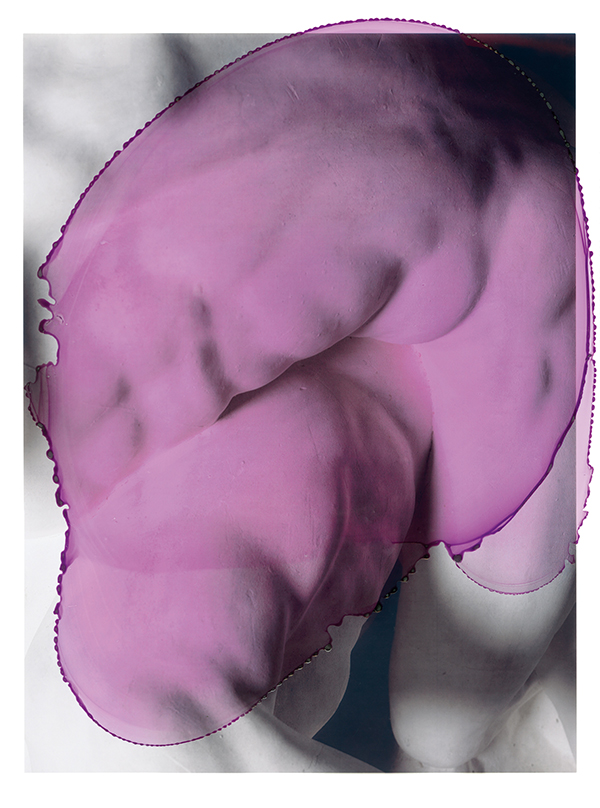

Viviane Sassen, Venus & Mercury, 2019

The Palace of Versailles has been fetishized by photographers since Eugène Atget—“a Balzac of the camera,” in Berenice Abbott’s words—first fixed the crumbling statuary of its gardens in his romantic gaze early in the twentieth century. More recently, Luigi Ghirri created photographic puzzles of the place that shift between fiction and fantasy, Candida Höfer explored its social architecture, and Robert Polidori captured its epic decorative constructs. For her most recent work, Viviane Sassen has applied her distinctive visual style to the storied location.

Versailles, as imagined by Louis XIV, began to take form in 1661; in 1682, it became the principal royal residence of France until the start of the revolution, in 1789, under Louis XVI. It offers a visual history of French architecture from the seventeenth century to the end of the eighteenth. The centerpiece of the monumental palace is the Hall of Mirrors, commissioned by Louis XIV to prove the artistic and political superiority of France to the world. Its seventeen mirror-clad arches reflect seventeen arcaded windows that overlook the extensive gardens, with their symmetrical flower beds and classical statuary, landscaped by André Le Nôtre.

Over six months, and on those privileged occasions when the palace was closed to the thousands of daily visitors who invade the grounds, Sassen roamed the empty mirrored halls of the palace alone, detailing the rococo chambers and the extravagant gardens, exploring both its most famous attractions and those secret spaces inaccessible to the public, including the private rooms of the king’s mistresses, the small libraries, the servants’ quarters, and even the Galérie des sculptures et des moulages, where weather-worn sculptures are repaired or shrouded from the bite of winter. Her body of work (or rather her work of bodies), titled Venus & Mercury (2019), was commissioned by the Palace of Versailles and curated by Alfred Pacquement, the palace’s curator of contemporary art, and Jean de Loisy, director of the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts de Paris, as part of an ongoing series of artist collaborations with the estate.

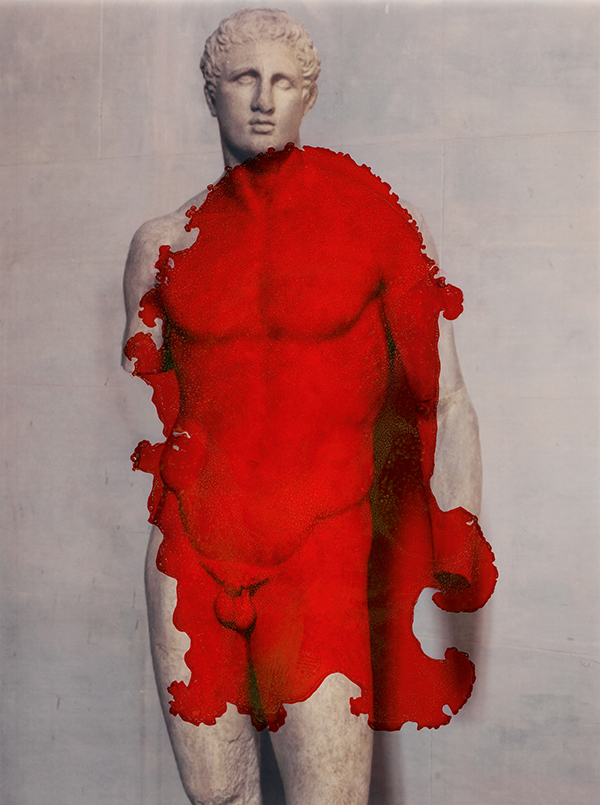

By her own admission, Sassen is an intuitive photographer who does not always come to a project with a specific concept or strategy, but allows the work to evolve over time and take on meaning as the process unfolds. However, she was immediately intrigued by the systems and signifiers of power and sexuality at play in the royal court, and particularly those inherent in the omnipresent statuary that populates the interiors of the palace and punctuates the geometry of its gardens. The rigidity and the restraints of court etiquette, with its hierarchical structures, became the entry point for an exploration of historical division and conflict, while at the same time conjuring in the artist memories of her own adolescent sexual awakening. “I had been there once before as a young teenager, when I was about fourteen,” Sassen recalls. “It was the first time I had visited Paris with my parents, and the palace made a huge impression on me. There was something about the statues in the garden. I found it an extremely romantic place and fantasized about what had happened there.”

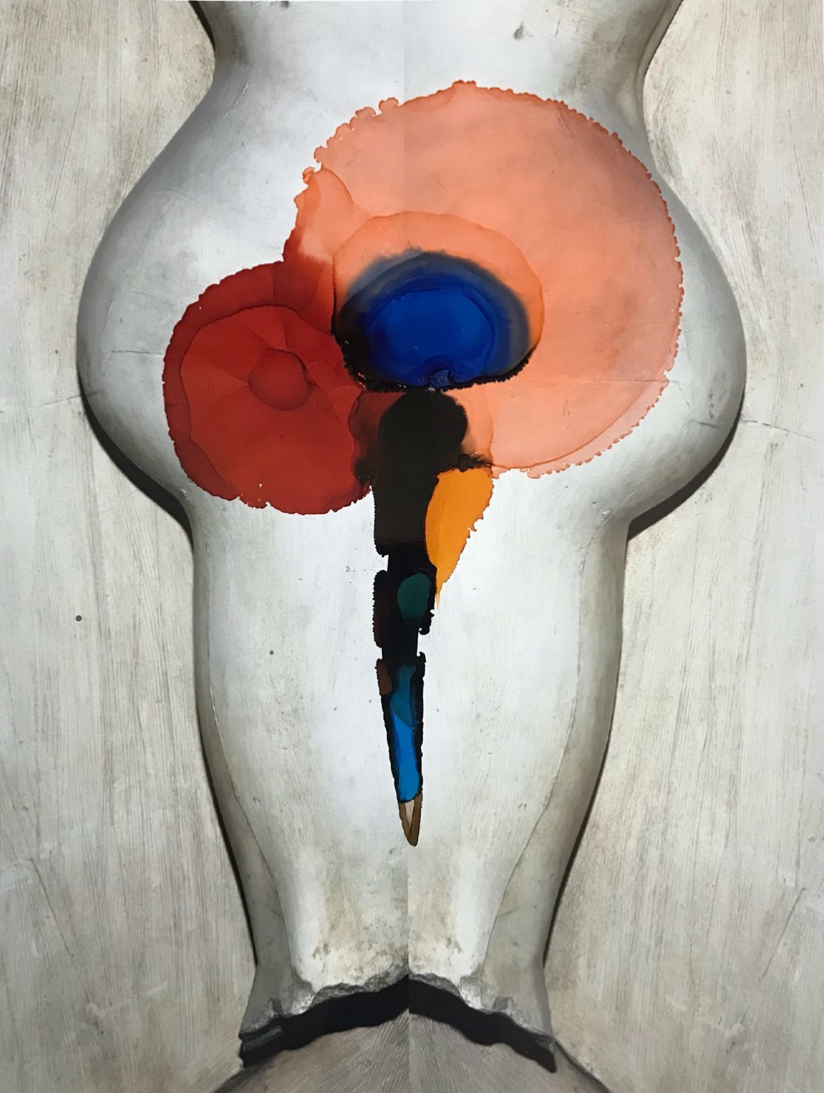

As suggested by her photomontage techniques, which are reminiscent of Hans Bellmer’s disjointed fantasies and Hannah Höch’s subversive collages, Sassen has always been drawn to the surreal. During her research, Sassen was particularly captivated by metal prosthetic noses from the period that were used by victims of syphilis—an affliction rampant in the royal court—whose own noses had been eaten away by the disease. This forbidden and forgotten relic of sexual decadence and deformity acted like a talisman for the artist. Sexuality and decay, disfigurement and dilapidation permeate Sassen’s vision as she gazes on these frozen totems of privilege, class, and power and liberates them from the sociopolitical and historical codes to which they have been bound by convention and academia.

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg. All sculptures belong to Musée du Louvre and Château de Versailles

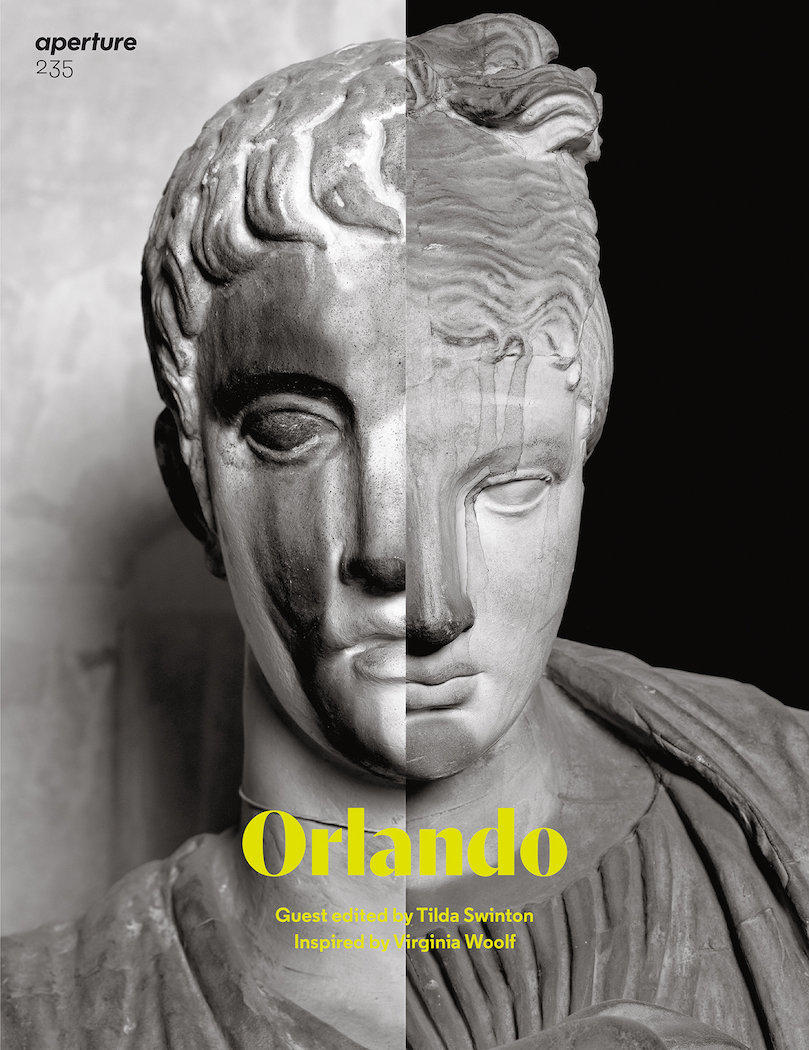

Venus & Mercury proposes its own vertiginous mirrored labyrinth in which disembodied halves are reflected and morph into unexpected wholes; bodies are severed and faces sliced in direct conflict. Sassen seems to be proposing new mutations within her gallery of biomorphic, almost hybrid creatures. Her photomontages echo the assemblage sculptures of German artist Isa Genzken, which transform and transfigure familiar objects and invite the viewer to consider a new way of being, a new way of seeing beyond the constraints of a binary system of values and aesthetics. They welcome us into a nonlinear narrative as a tribute, a reminder, and an open question. In the same way that Virginia Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando, which follows the long life of a young nobleman across centuries and genders, plays with possible realities and challenges social impossibilities, Sassen’s work on Versailles infiltrates historical corridors of power to offer a more universal consideration of the limitless potential of the human condition. “I try to make images that have the ability to free your mind in some way and to look at something from a different perspective,” Sassen reflects. “I always try to avoid too much context. I isolate these things in order to make them more abstract. My images are like a hall of mirrors; they reflect back at you what you already have inside.” In her own visionary sculpture garden, these figures are no longer frozen in time and space. Restored and repaired, they are alive and resonant with new meaning. Stripped of wealth, gender, and history, they inhabit an ambivalent space, a world in-between.

Read more from Aperture issue 235, “Orlando,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.