Why Do These German Citizens Dress up as Native Americans?

Here are the Indianer bodies: braid-framed German faces and shirtless, toned torsos. And here are the material goods, products of a curious labor of desire: bright canvas tipis, brain-tanned deerskin, perfectly crafted feathers, quilled and beaded clothing that mimics Karl Bodmer paintings from the 1830s. Bodies and goods join together in performances, as drums pound, legs step, and voices sing—or sometimes just yell. Document these things and you have archives—a museum stuffed with mannequins, a wall hung with moccasins, a computer full of images.

For German hobbyists who participate in the Indianer subculture, which revolves around Native Americans, their devotion culminates in annual summer camps where they show off their skills and live the Indianer life for a week. Their scene (for it is truly that) originated with the late nineteenth-century writings of the German author Karl May, whose characters—the Apache chief Winnetou and his German sidekick Old Shatterhand—inspired Europeans’ fanatical affection for North American Indians.

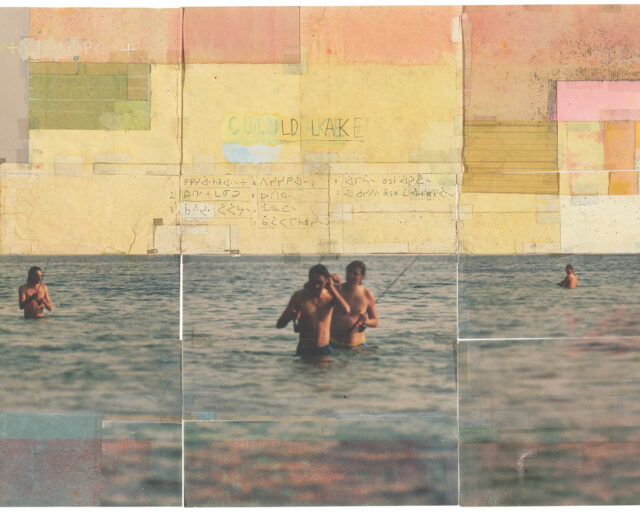

Into that scene, carrying a camera, steps Krista Belle Stewart, an Indigenous Syilx Nation artist based in Berlin. What Stewart enters, on visits made over a period of several years, is multiple layers of the uncanny. The hobbyists’ dedication to authentic detail seems at first to evince a deep respect for Native cultures. But the escapism also embodies a reassuring flight from compromised German histories. Stewart’s presence reminds them that there are moral quandaries surrounding history and appropriation yet to be considered. Indianer, shrinking in number and uneasy, know this to be true.

What of Stewart herself, sitting with a friend in a replica of a Plains Indian lodge in a German field? “What’s weird about the experience,” she told me, “is that they are real . . . but I can’t quite believe it. Because we are real too.” She spoke of returning to her homelands after each trip, a cleansing restoration for an Indigenous sense of self pushed a touch off-kilter. After visits in 2006 and 2007, Stewart stepped back from her explorations of Indianer culture, unable to reconcile the contradictions. She returned in 2019, though, and quickly rekindled old relationships. One hobbyist, who had made Stewart a dress more than a decade earlier, retrieved it from a subsequent owner and gifted it to her.

That dress and a silver arm cuff gifted to the artist by another German enthusiast are the only two objects situated vertically in her 2019 exhibition Truth to Material, held at Nanaimo Art Gallery in British Columbia. For the rest of the installation, Stewart arranged images of four different scales in an asymmetrical grid on a vinyl-covered floor. Stewart’s bare walls reject the exotic and documentary photographic traditions associated with Indigenous subjects. Instead, viewers teeter over the images, positioned in a vertiginous uncanny.

The floor also brings viewers into an Indigenous judgment. In many Native cultures, one does not step over another’s body or belongings. To do so is a sign of disrespect, even a provocation. Such stepping is the essence of the exhibition, and for good reason. As Stewart observes, when Indigenous people contemplate Indianer life, they laugh. And then they feel anger. She is aiming for the complete package—not simply wonder, irony, and humor, but also a sense, understood but less often experienced, of Indigenous indignation.

All images courtesy the artist

This interview was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the title “Truth to Material.”