LaToya Ruby Frazier and the Notion of Justice

Frazier speaks about the photographic legacy of the civil rights era—and being a witness to our time.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Flint residents and students from Northwestern High School await the arrival of President Barack Obama, May 4, 2016

Kellie Jones: Let’s start with your 2014 book, The Notion of Family. Did the popularity of The Notion of Family surprise you, especially given the subject matter? Members of your family have been supportive and willing subjects. Sometimes in such exposés we might feel victimhood. How have you crafted your approach differently?

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Initially, when I started The Notion of Family, I knew that I needed to make something on behalf of my relationships with my mother and my grandmother, and something that was for me.

Growing up in the 1980s in the Rust Belt in Braddock, Pennsylvania—a time when cities are shrinking, all the factories have been outsourced, all your social services have been cut, the schools are closed, the library is barely functioning—I was already dealing with an invisibility complex. And I didn’t really understand why we were next to this factory, caught in the shadow not only of the Edgar Thomson steel plant, but also caught in the shadow of Andrew Carnegie. What does that mean to have to measure yourself, or try to be seen, through an industrial capitalist?

Even though I was a teenager and I didn’t have the language to articulate what I was seeing, I knew that I was dealing with shadows and invisibility, and dealing with toxicity and pollution, and then dealing with three generations—or really four, but I didn’t meet my grandmother’s mother—of women who grew up in three different social and economic periods. For my grandmother growing up in Braddock in the 1930s it was very different, because it was a bustling melting pot. None of us are fully black, but we’ve led our lives as black women. Then my mother growing up during the 1960s period of segregation, and then myself growing up there in the 1980s during the “war on drugs” and the abandonment.

The Notion of Family is the book of speaking to my younger self as an adult now, understanding what I know now, but also the coming-of-age story of what it means to grow up in a postindustrial, post-Fordist society, and the post-Reagan era. And what does it mean to be a black woman, inserting yourself, talking about the politics, talking about the toxicity, talking about industrial capitalism?

Courtesy the artist

KJ: How was it collaborating with your family?

LRF: It’s a precarious situation. Grandma didn’t like to be photographed. She always said, “Go photograph yourself.” That’s what caused me to start doing self-portraits. My mother, as soon as I came in with the camera, instantly had ideas. But a lot of it revolved around surgery or operations, or having cancer removed from her breast, or just coming out of the hospital, and the same thing for my grandmother, except I didn’t realize that she was dying from pancreatic cancer, because she never said anything. And I’m trying to figure out who I am between these two women, but at the same time our bodies are deteriorating in the landscape, because the three of us all have terminal illnesses.

KJ: Has your practice always combined issues of environmentalism and race?

LRF: When you’re a teenager making portraits, you don’t realize that. You’re just taking the class, trying to get the composition and the formal language. But it became very clear to me the day I went into the Carnegie Library. I pulled out this book, Braddock, Allegheny County. I took it back to my studio, and I’m turning through the pages. I knew the editor. I knew everyone who contributed to it. I knew everyone who wrote for it. And I got to the end and there wasn’t a single African American in this book. And it was published in 2008 and I just couldn’t understand how that was possible. So here I was innocently, quietly making these portraits of my mother and grandmother, and then it all changed when I saw the book. And it hit me: Okay, this has a bigger significance. This is not about you. You’re in it, but really you’re talking about how to rectify the fact that a large population of people has been omitted and erased from history, and continually silenced. So I felt intimidated by it, but I also was so outraged by it. I had a bigger mission.

And that’s when The Notion of Family started to come into my mind, thinking about The Family of Man and what that show meant to American history, and the timing of the show in 1955, and thinking about Emmett Till being killed months later and the power of that photograph, and how images do spark memory, history. Activism starts to take place because images become available of something that wasn’t visible.

Courtesy the artist

KJ: Can you talk about the impact of the MacArthur grant and how that changed your relationship to Braddock and Pittsburgh?

LRF: Prior to the MacArthur I was seen as an angry, disgruntled little black girl who doesn’t know what she is talking about, and doesn’t have the right to talk about civic duty, and isn’t allowed to point out how Braddock is being gentrified, and isn’t allowed to point out the rebranding of it, and how it’s becoming homogenized and not including the people of color, and the working class, and the elderly, who have always occupied this community. I kept being reduced and dehumanized and silenced. It wasn’t until I got the phone call that day and it became public, that all of a sudden Pittsburgh was proud. I was seeing my name in the paper. I had just moved to Chicago, but they were claiming it, and then so was Chicago. I was having to do interviews in both places. One time they said, “Well, is there anything left you would want to say, LaToya?” And I was like, “Yeah, I hope I make Pittsburgh proud.” [Laughter]

Courtesy the artist

August Wilson was on my mind when I received the MacArthur. And when I think about it, even though I’m using photography and performance and video, it is speaking exactly to what he was doing, which was telling and narrating the daily stories and lives of working-class black people that are constantly overlooked. I really believe that if you can talk about the history of this country and the steel industry through Andrew Carnegie and all these other Scotsmen, then you can talk about America and its history through black women, through black men, and through black children.

I’m talking about being working class. I’m talking about being poor. I’m talking about being blue-collar. Our own presidents don’t say “poor” or “poverty.” They say “middle class,” and I’m very agitated about that.

© and courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

KJ: You’re certainly bringing that into view for a lot of people. I’ve taught your work in a course on Gordon Parks. I’ve seen you, along with Hank Willis Thomas and Mickalene Thomas, as heirs not only to his photography practice, but also to his sense of interdisciplinarity, as well as social justice. How does your interest in photography and video differ from his?

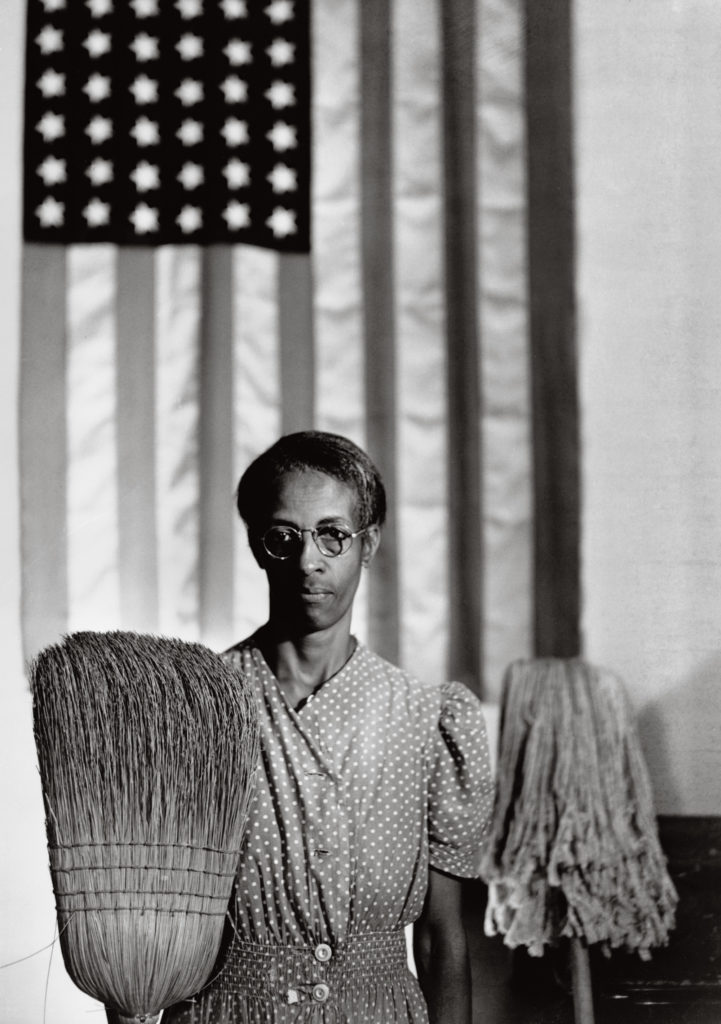

LRF: Parks’s American Gothic (1942) was one of the first images that I saw by him, in my photography class in undergrad, and it shook me up. To see Ella Watson standing there mimicking Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930)—I realized that this is a photographer in conversation with a painting, and a painter. Then I also noticed: Here is this woman, working in a government building in Washington, D.C., and nobody sees her, and she’s the janitor who’s cleaning and sweeping every night. But Gordon saw her, and it was the first time I realized that I can speak through a photograph. It’s not about taking the picture. It’s about making the image because you have something to say. She was only making what is equivalent now to $15,000 a year, and she had her children.

© the artist/Magnum Photos

KJ: And grandchildren.

LRF: And that’s how she was supposed to survive? So that image really pushed me to start to become more accountable and more responsible to what I wanted to say. But importantly, I learned about Gordon Parks from a homeless woman. I was photographing in a homeless shelter and when I handed this woman her portrait she said, “This reminds me of a photographer I saw on TV on PBS. Do you know Gordon Parks?” And I didn’t, but as soon as I left I went and bought all of the books I could get my hands on. It was because of my encounter with all of his works and reading A Choice of Weapons (1966) that I changed. I’m in pursuit of what Gordon Parks achieved. I’m trying to add to that legacy, but add to it as a young woman and a young practitioner giving voice and collaborating with more women, more populations, but also seeing them as equals.

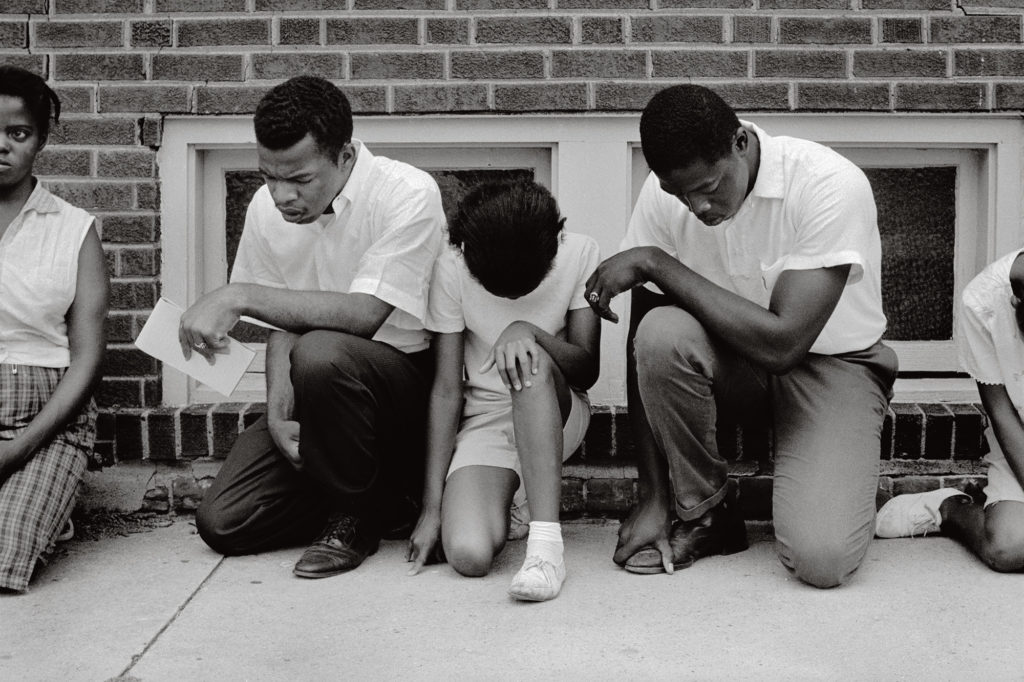

I want to ask you about Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties, the exhibition you curated at the Brooklyn Museum in 2014. When I came to Witness and saw the Bruce Davidson, the Gordon Parks, the Charles White, it all really started connecting for me in terms of what I was doing. I realized, Okay, LaToya, you are doing social activist work. I always had this feeling like it just wasn’t enough. And then I saw the exhibition and I realized I was part of a long tradition and a long conversation, and it brought me so much more insight and confidence. Could you talk about the timing of the show and bringing this period, the 1960s, forward through the museum?

© the artist/Magnum Photo

KJ: Witness celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, which was about guaranteeing civil rights for all in this country, regardless of race, creed, or color. So we started with that 1964 date.

What was exciting to me was to see so many interesting things that happened in that year artistically. It was Romare Bearden’s breakout moment. He’s been painting for years. He’s in his fifties. People decide they love his collages. He’s also using photographic material in these works.

One of the major things when we think about photography is that most people know the civil rights movement through it, through the photography of Danny Lyon, of Gordon Parks, and through television, but they didn’t know about it through painting and sculpture.

LRF: I was definitely enlightened, and wish I got to study with you. When I was speaking earlier about being held accountable and responsible, not only was I challenging the narrative from my hometown and the narrative that we were all presuming to understand about how the Rust Belt is being developed, or the difference between working-class and creative-class theory, and our complacency as people from the creative sector and industry within that. I was also making it a point to bring people from my community into the institution.

So you have Witness, and Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960–1980 (2011), which you curated for the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, happening right in the midst of this other burst as Obama’s leaving, and you’ve got Black Lives Matter, and you’ve got “riots” coming out because of people resisting police brutality, understanding that the boys in blue could be a gang like the Bloods and Crips. All this realization happening in the American psyche. And the fact that everyone is having this meltdown, even considering Trump and Clinton. We’re just so disillusioned and unhappy, and also desensitized at the same time about the history, the murderous onslaughts that we’ve done in this nation. Am I one of those artists contributing and being a witness to my time?

Courtesy the artist

KJ: You’re definitely a witness to your time. You’re telling us about Braddock. Many of us didn’t know about it. And, like you said, it’s representative of places all over the country, and really all over the world.

LRF: I want to close on the Flint work. I had been tracking the Flint story, and then Mattie Kahn, who profiled me for Elle after the MacArthur, reached out and said she wanted me to cover the story. I initially said, “No way. This is Elle. It’s fashion. Why in the hell would I, of all people, want to deal with you?” Then I started thinking about Gordon Parks. Well, he was with Life; he was with Vanity Fair and Vogue. This is the next step, right? You want to impact mainstream culture, the masses. You want to get these things in front of them. So I decided to go.

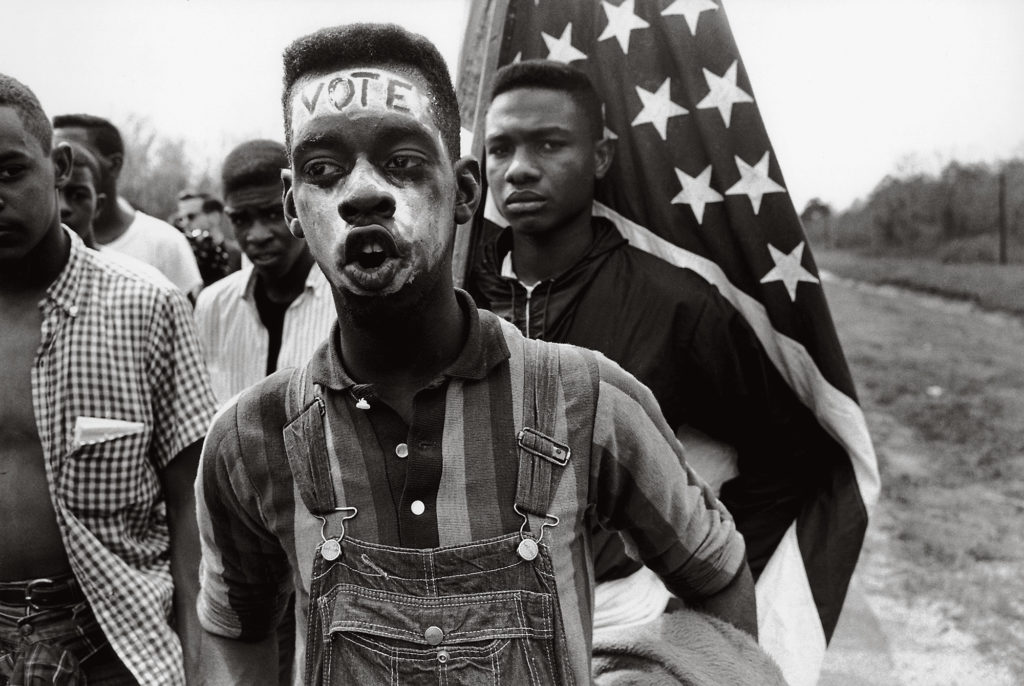

And the fact that this is contaminated water: Water is a human right. Water is life. And the fact that no one’s even looking anymore. Clinton is not there. Bernie Sanders is not there. No more free concerts to raise money. As I was packing up to leave, a kid grabbed this poster of Governor Snyder and brought it over to me. He wanted me to see something. He had something to say. He wanted me to document it, and I thought about Witness. I thought about all those photographs, because when I looked at him, I could see that language of the civil rights era, and I couldn’t help but shoot it. Everything from that exhibition came forward and I thought, You have to shoot this. So I grabbed my camera back out and I shot it. I’m thinking about the fact that Gordon was also mindful. Just because people were living in what looks like squalor, which is really the landlord’s fault, they were still educating themselves. They were reading; they were studying; and he was making photographs of people reading their books and studying, in addition to going through the whole system that keeps you trapped. Then there’s the image of Obama drinking the Flint River water. I was dying to get that photograph. I kept asking, “Where is someone I can photograph watching him drinking the water?” I knew I needed it to be this historic image.

This conversation is adapted from a public talk between LaToya Ruby Frazier and Kellie Jones at the Strand Book Store, New York, in October 2016.

Read more from Aperture, issue 226, “American Destiny,” Spring 2017.