A Witness to Resistance

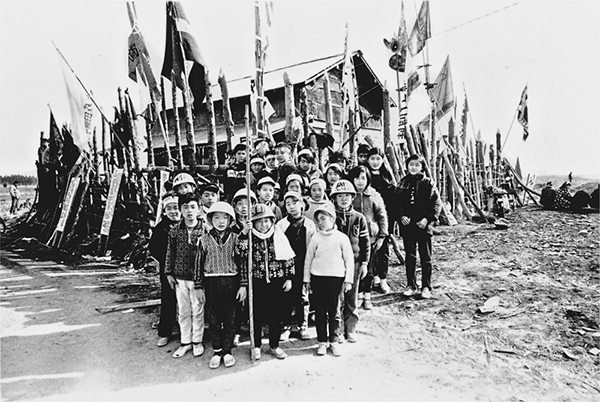

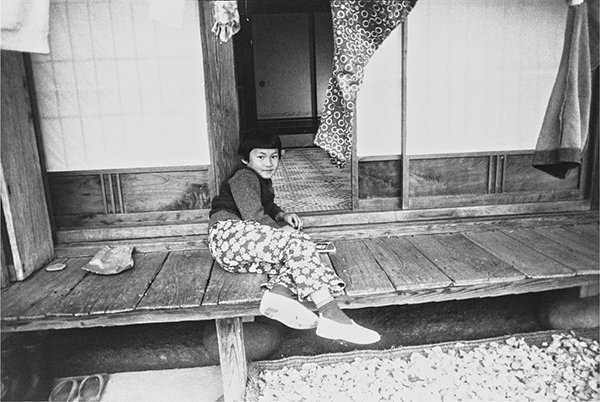

Kazuo Kitai, Childrens’ Resistance Corps, 1970, from the series Sanrizuka, 1969–72

© the artist

“I wanted my pictures to be just the opposite of what passed then for excellence,” Kazuo Kitai remarked in the introduction to Barricade, his 2012 monograph. His blurry, out-of-focus snapshots from the 1960s were radical in style and substance. In 1965, at the age of twenty, Kitai published his first book, Resistance, which pictured the 1964 demonstrations near the U.S. Navy base in Yokosuka. From 1966 to 1967, he worked exclusively for political student groups, documenting their protests. When Zenkyoto, or All Student Union, came to power in 1968, he joined the students occupying Nihon University. The following year, he moved to a village east of Tokyo called Sanrizuka, where local residents clashed, often violently, with the government over the construction of a new airport. In the ’70s, Kitai left Tokyo and shifted focus to photograph rural landscapes and families. Tsuyoshi Ito of A/fixed spoke with Kitai about his engagement with photography and protest.

Tsuyoshi Ito: How did you first get into protest photography?

Kazuo Kitai: In 1964, during my second year at Nihon University, an acquaintance invited me to photograph the anti-nuclear submarine demonstrations. I shot seven rolls of film that night, and developed them right away. I thought, “Wow, these aren’t bad!” I continued my photographing protests, but at first my subjects weren’t pleased with my photographs. At the time, the student movements were treading water. But things began to heat up in 1968 when the All-Campus Joint Struggle League formed and the Barricade Strike demonstrations started taking place throughout Japan.

Ito: Were you working independently?

Kitai: At first, yes. The Asahi Journal and Asahi Graph magazine were covering the student movement and selling quite well. The editors were pleased, but found the accompanying photographs, shot from afar with telephoto lenses, to be sterile and lacking. My first assignment was shooting inside the barricades of the student protest at Nihon University’s College of Art. The publication dedicated a six-page spread to my photos. They titled it something ridiculous like, “Violent Radical Student Protest.” No one on the outside knew what the conditions were like inside the barricades. People were interested in that. My photographs started to develop a good reputation, and I soon had a monthly assignment.

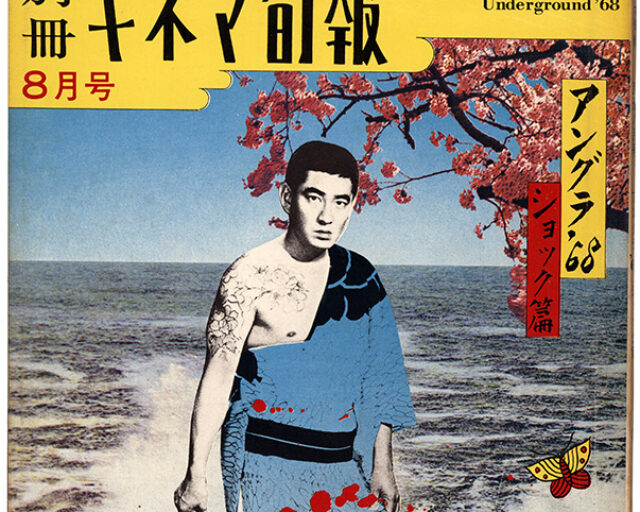

Kazuo Kitai, In front of the Basement Gates, Yokosuka Kanagawa, 1964, from the series Teiko (Resistance), 1964–65

© the artist

Ito: You published several books on the student protests. How were they received by your subjects?

Kitai: Barricade (1968) was one of my first collections of protest photography. At first, there was tension in the air. But as time passed, people became accustomed to life inside the barricade. It was common to see laundry hanging out to dry, people’s beds, and living spaces. Many of my photographs from inside the barricade depicted daily life. I thought that was cool, but the student protesters didn’t like those photos. On the other hand, the collection Agitators (1968), contained intense scenes of protest, and was a hit among the students.

Ito: What was your next stop after photographing the student movements?

Kitai: In the late ’60s, the government had plans to build a new international airport (near Tokyo), Narita, and the farmers in the area fought to defend their land from appropriation. I began visiting Sanrizuka, a farming village at the center of the struggle. I contacted the editors of the Asahi Graph with a proposal that I stay and shoot in Sanrizuka for two years, and they agreed. From 1969 to 1972, I photographed the daily lives of farmers as well as their protests.

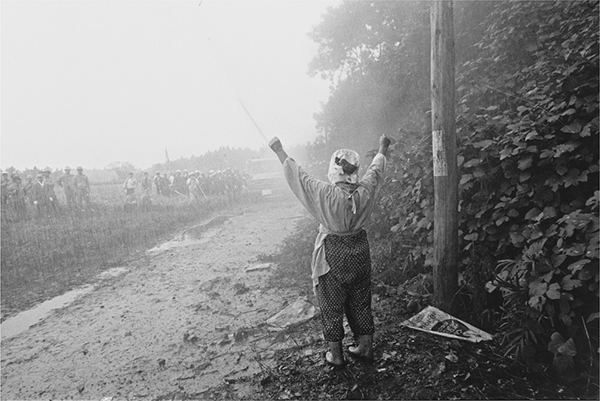

Kazuo Kitai, Old Lady Faces the Water Cannon, 1970, from the series Sanrizuka, 1969–72

© the artist

Ito: How did that experience influence your photography?

Kitai: My perspective changed completely. A common perception is that photographs simply record events as they unfold. But I came to believe that a photograph is a conversation between the photographer and the subject. That really influenced me, and even today I try not to force my shots. I prefer that both my subject and I both act naturally, and I think my photographs capture that.

Ito: What was the political climate at the time of the student protests?

Kitai: There were two major student movements at the time: the Liberal Revolutionary Student Movement, which was very political, and the All-Campus Joint Struggle League, which was more focused on the democratization of universities. I photographed them both. Requests started to pour in from newspapers, always wanting more and more provocative photographs. But I wasn’t really interested in that type of photography. I was living with the protesters, but I never really got radicalized. I wasn’t there for the action.

Slowly, the photos that were requested of me and my idea of what my photography should be began to diverge. And I was fine with that. I realized that if I wanted to become a professional photographer, I would have to be serious about my craft. Shooting a demonstration is simple. There’s always something happening, you just point and shoot. I wanted to come up with a theme that resonated with me, and the first thing that came to mind was Eugène Atget and his photography of everyday people in Paris. That really appealed to me and I thought I could try something similar.

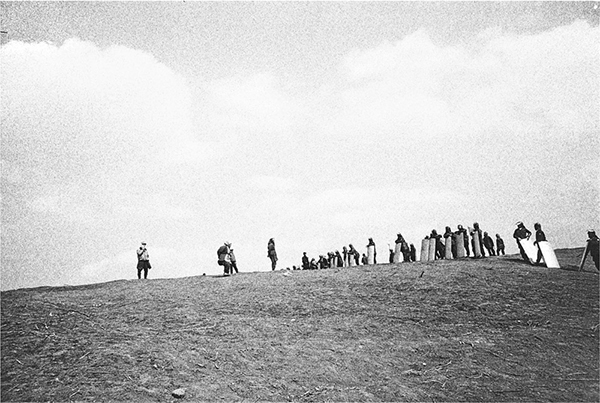

Kazuo Kitai, Women Facing the Police on a Hilltop, 1971, from the series Sanrizuka, 1969–72

© the artist

Ito: But before you changed direction, you were very involved in the protests?

Kitai: Behind the barricades I threw Molotov cocktails along with the student protesters. In Sanrizuka I was ready to be arrested at any time. I was a photographer, but I was also a part of the resistance.

Ito: So you wanted to bring about societal change through your photography?

Kitai: I never even considered that. Of course photography is a form of expression. It has the power to influence people and even change society. But I never took a picture with that in mind. I think that if you take photographs with that kind of intention, then your product will be necessarily altered.

Ito: You didn’t see your photography as political expression?

Kitai: Politics is power and violence. Strength passes for power in politics. But I was only armed with what I could express through my lens. There was no overlap between politics and the pictures I was interested in taking. I don’t like depressing photography. I prefer photos with more humanity—photos that encourage empathy with the subject. You can see this in my series To the Villages (1973–81).

Kazuo Kitai, Washi Village, Agawa district, Kochi prefecture, 1973, from the series Mura e. / To the Village, 1973–81

© the artist

Ito: The human element is important to you?

Kitai: Yes. I don’t have many critically acclaimed photographs, even from my days as a protest photographer. But my subjects would often ask me to send them prints. It was a different time then, as opposed to now where photos are readily available to anyone. My subjects would keep it as a memento, showing their friends, “Look at this picture that one famous photographer took of me!” I knew how important it was for them, so I made it a priority.

Ito: How did your subjects react upon seeing To the Villages?

Kitai: They loved the photographs, same with the farmers and protesters from Sanrizuka. I think it was because I lived with them. I understood them and respected their lifestyle, and my photos mirrored their own perspective in an intimate way. It was popular at the time to appeal to viewers by highlighting someone’s hardships—showing the wrinkles on their sunburnt faces and their leathery hands. But the subjects themselves didn’t like that. I prefer to highlight the good side of people, to capture their presence and the reality of their existence.

A/fixed’s inaugural publication, Provoke Generation: Japanese Photography, ’60s-’70s will be released in April 2017.