Rosalyne Blumenstein and the Art of Living

“My transition from young white boy with a false sense of privilege in the 1970s to young tranny-girl with little or no privilege was a real smack in the face,” Rosalyne Blumenstein wrote in her 2003 autobiography, Branded T. “My spirit and soul seemed to be uplifted and smashed on a daily basis.”

Blumenstein is an icon. I met her, in 1993, when I came to New York as a newbie trans activist from San Francisco and visited the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center, where Blumenstein, a self-described “woman of transexual experience,” lent street cred as director of the center’s pioneering Gender Identity Project, which included an HIV-prevention program for trans people. Blumenstein didn’t invent the word transgender, but she popularized it through her public-health work.

Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles

Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles

I doubt she remembers that brief encounter. Although we are only a year apart in age, I was just getting my feet wet (head first) in the trans scene, while she’d been in the life a long time. Blumenstein lived as I’d been afraid to live as a young teen, struggling with my gender dysphoria, fearing the only way to be the person I was to become would be to abandon everything for a walk on the wild side of Manhattan. Blumenstein’s path from Canarsie, Brooklyn, to Forty-Second Street was shorter than mine would have been from small-town Oklahoma, but she nevertheless had the huevos to transition at sixteen, which I didn’t manage until thirty. She boldly lived what I but timorously imagined.

Courtesy Rosalyne Blumenstein LCSW

Courtesy Rosalyne Blumenstein LCSW

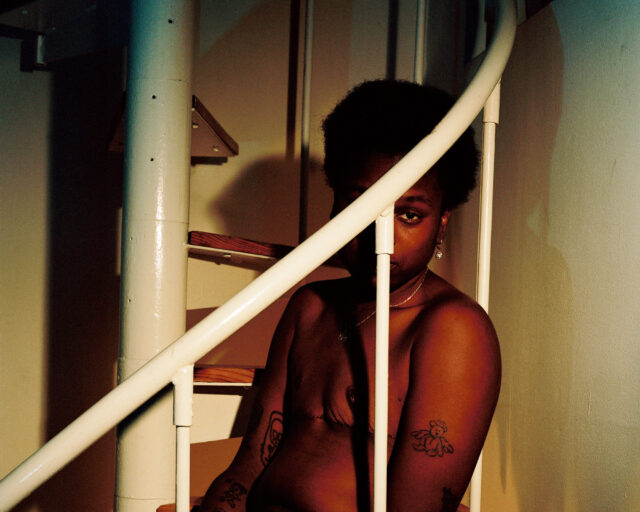

A generation after her heyday in the demimonde, Blumenstein relocated to Southern California and became, among other things, muse and mentor to LA-based trans multimedia artist Zackary Drucker, who regards Blumenstein as one of her legendary foremothers—an iconically feminine, decidedly binary-gendered incarnation of Botticelli’s Venus. The power of an iconic image is its capacity to simultaneously represent many desires, however contradictory or mutually exclusive, that exceed everything invested in it. For me, Drucker’s recent photographs of Blumenstein embody the fantasy of the fierce, street-smart trans girl who survives into empowered womanhood—a lived reality attested to by Blumenstein’s own compelling photographic archive.

Blumenstein is that actualized fantasy and more. The neither/both/other-than of trans-ness layers itself—a powerful, unasked for, and sometimes unwanted gift—atop even the most intransigent of our identifications. As a child, Drucker was enthralled by the fantasy of magical metamorphosis that Tilda Swinton portrayed in the 1992 film Orlando. She sees Blumenstein through that lens: a doubly amphibious, alchemical lady in fiery red, straddling earth and water in open air. Swinton’s own affinity with Orlando similarly lies in her perception of that character’s freedom to break the bonds of binary gender and roam the open territories beyond particular identity. Transgender has long iconized the fantasy of limitlessness.

Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles

In practice, flesh—as with any material medium—is not infinitely plastic, nor are our identifications. The cut that accomplishes one intention inevitably constrains another, whether physically or psychically. Yet as Drucker’s images, Swinton’s editorial vision in this issue of Aperture, and Blumenstein’s lived experience all attest, transgender can function as an art of living that enacts, destroys, and elevates the intent it seeks to realize.

Read more from Aperture issue 235, “Orlando,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.