America on the Brink

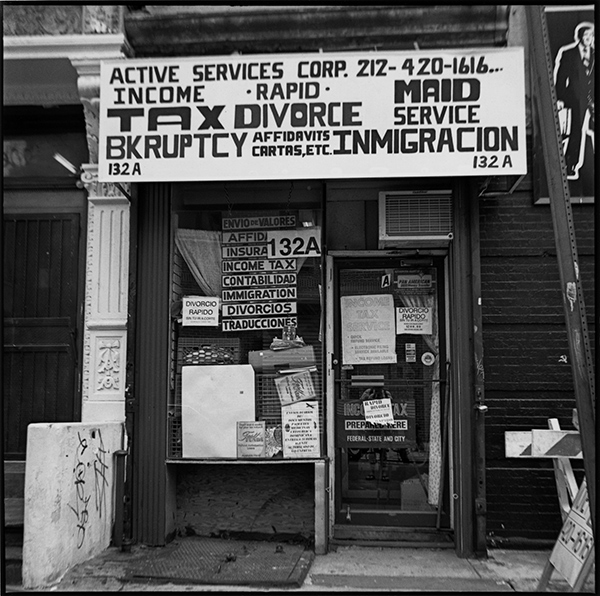

Zoe Leonard, Income Tax, Rapid Divorce, 1999

Courtesy the artist, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and Hauser & Wirth, New York

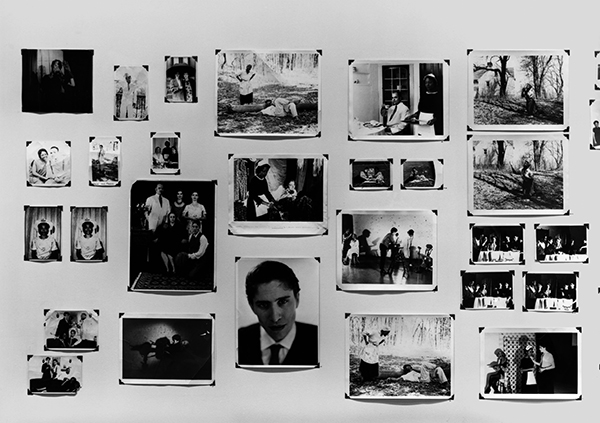

“Why does she look so surprised at the flowers?” a man asked of his companion on a recent afternoon at the Whitney Museum of American Art. He bent closer to the glass to inspect a publicity still–style photograph of a woman wearing a maid’s uniform, brandishing a vase of florals and an exaggerated, startled expression—an image from The Fae Richards Photo Archive (1993–96), Zoe Leonard’s photographic narrative of the fictionalized subject of a faux documentary by Cheryl Dunye. In photographs and film, Leonard and Dunye invent the story of Richards, an African American lesbian actress in twentieth-century Hollywood, who gets work playing slaves and maids (as in the aforementioned still), comes to fame for her role as the “Watermelon Woman,” lives a thinly closeted existence, becomes an activist in the civil rights movement, and, after her career is derailed by racism, slips into obscurity.

“Ah!” the man said. “A burlesque-y show. It makes sense.” He parsed through more of Leonard’s prints, presented as an archive of found photographs, in a glass-topped display box: pictures of Richards performing onstage topless, in a skirt made of bananas, lounging with her supposed lover in a park, blowing smoke rings under a spotlight. “I never heard of her before,” he continued, seemingly baffled that he hadn’t.

It’s a testament to the successful verisimilitude of Leonard’s staged photographs, created to mimic various vernacular and formal styles over the decades—snapshots, press clippings, a luminous series of black-and-white portraits that make for an affecting rendering of a very conceivable life—that they can inspire such genuine befuddlement. Leonard’s work, on view in Zoe Leonard: Survey, her first solo exhibition at the Whitney, invites that kind of pliable, multi-tiered appreciation.

Zoe Leonard, The Fae Richards Photo Archive (detail), 1993–96. 78 gelatin silver prints and 4 chromogenic prints

Courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art

Leonard’s massive display of vintage postcards of Niagara Falls, You see I am here after all (2008), speaks to the desire to see the thing that everyone else has seen, and to own it, and the impossibility of doing so. The tangible image recorded in a postcard is what visitors to the falls will keep, and likely, it’s what drew them there in the first place, perhaps via the mailing of a similar postcard, signed—as the ones here are—by Alice, Edna, Bert, “Father,” and “A True Friend.” (The title comes from a line handwritten on one of the cards.) The postcards—hand-colored, glitter-covered, color-saturated—reveal changes over time, preferred angles, rainbows appearing in the mists. Leonard makes towers of postcards that share the same picture; they form their own waterfall. Museumgoers sit down on benches, stare: rippling along the wall, the waterfall postcards are nearly as calming and mesmerizing as the real thing.

In another room, more Niagara postcards are stacked on a workhorse table and arranged in piles corresponding to the various vantage points and depictions of the falls. Here, they speak to the collecting and archiving of memory. Barred from getting too close to the table, one has to crane in order to read their straightforwardly descriptive and accidentally evocative titles: Brink of American Falls, American Falls From Below, American Falls from Canada. On an adjacent wall, Leonard’s own photograph of Niagara Falls, made from above, is a gelatin-silver print that depicts a boat at the foot of the falls, caught in the horseshoe semicircle. You can sense the roar in the dark grain of her print; it swings between terror and beauty.

Zoe Leonard, You see I am here after all (detail), 2008. 3,851 vintage postcards. Installation at Dia: Beacon, New York. Photograph by Bill Jacobson

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

Elsewhere her other photographs likewise exist on dual planes. The forty photographs that make up The Analogue Portfolio (1998–2009) depict small storefronts—on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, in Poland, Cuba, Mexico, and Uganda—with crude hand-painted signs advertising cell phones, fried pastries, back-to-school shoes, bolts of fabric, and quick divorces, as well as sidewalk displays of still more shoes, brooms set in sandbags, mattresses in stacks. At the outset, they are the sorts of pictures a traveler might take; similar to William Eggleston, Leonard finds her subject matter in the quotidian and renders it in dye-transfer printing: the lurid, glorious, and now-extinct process previously used in commercial photography. Eggleston was attracted to the vivid, saturated color of dye transfers; Leonard is, too, but she reclaims the original purpose of the process, as if “advertising” these benign, independently run laundromats and barbershops in an artistic context. The series includes a photograph of a wooden drink stand painted bright red, save for its hand-painted Coca-Cola logo and a similar wooden, handmade, shack-like structure, painted pink, that bears a sign reading “ARTIST.” Leonard effectively places corporations and individuals—in particular, artists—on equal footing.

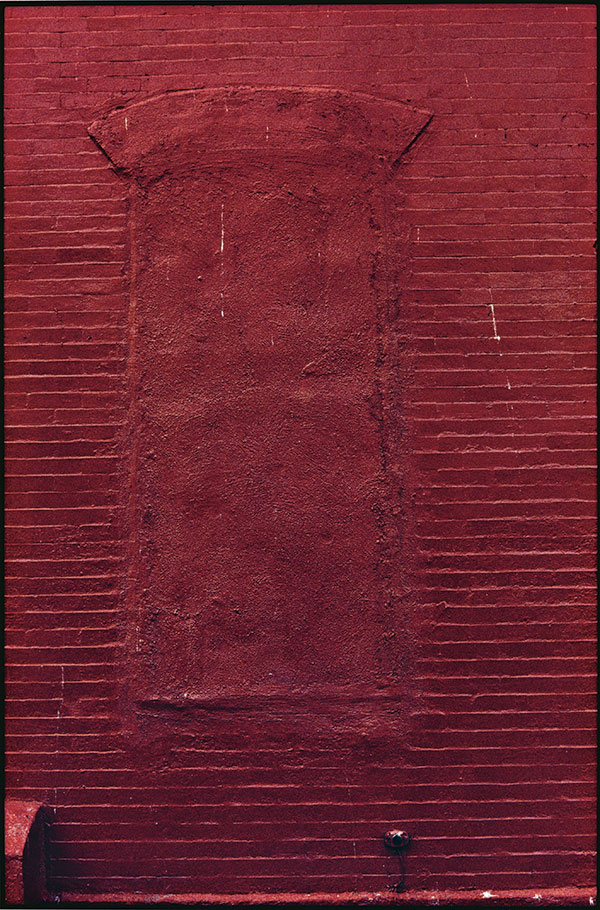

Zoe Leonard, Red Wall, 2001/2003

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne

These streets—ephemeral, endangered—are a mapping of the world, and of Leonard’s place in it. The wall text that opens Survey explicitly encourages all kinds of mapping, through place and time. In the first room, a row of blue vintage suitcases, one for each year of the artist’s life, includes space, perhaps superstitiously, for just one or two more; in still another room, stacks of a Kodak-published book on amateur photography. The installation How to Make Good Pictures (2016) shows the evolution of changes in the cover photo, design, and then, markedly, its title, which changes to How to Take Good Pictures. The verb switch from “make” to “take” signals a shift from the idea of creating a picture to “capturing” one. The stacks sit across from Leonard’s photographs, made from her own family’s pictures taken near the Statue of Liberty, records of recent immigration.

On personal and artistic terms, the show is a record of the various work that Leonard, born in 1961, has been making for decades, some of which has previously appeared at the Whitney, including Strange Fruit (1992–97), her installation of sewn dried fruit skins, dedicated to her friend David Wojnarowicz, which anticipates the Whitney’s retrospective exhibition of his photographs opening this summer. The museum’s physical place in the world has changed since Leonard began showing there: her first Whitney Biennial was in 1993; her most recent, 2014. In 2016, one of her best-known works, the poem “I want a president,” was blown up and wheat-pasted along the High Line park just north of the Whitney. Leonard had written it in response to Eileen Myles’s run for president in 1992, as an independent, but most notably, as a woman and as a lesbian. Now the poem hangs on the wall of her survey, in a smaller, 8-by-10-inch format.

Zoe Leonard, Untitled, 1989

Courtesy the Artist

One by one, visitors approach the work, aim their phones at it. Some stop to reread. As I did, I started thinking again about Fae Richards, whose invented but very real-seeming life is mapped in the other room, surrounded by Leonard’s photographs of anatomical wax models and chastity belts. “I want a dyke for president . . . I want a Black woman for president. I want someone with bad teeth and an attitude, someone who has eaten that nasty hospital food, someone who cross-dresses and has done drugs and been in therapy. I want someone who has committed civil disobedience.” Leonard and Dunye created a perfect candidate—it’s a shame that she is imaginary, and a shame that they had to let their protagonist die, to serve a verisimilar, documentary truth. Looking at those photographs, you do believe in her. After all, she exists everywhere. Fae Richards for President!

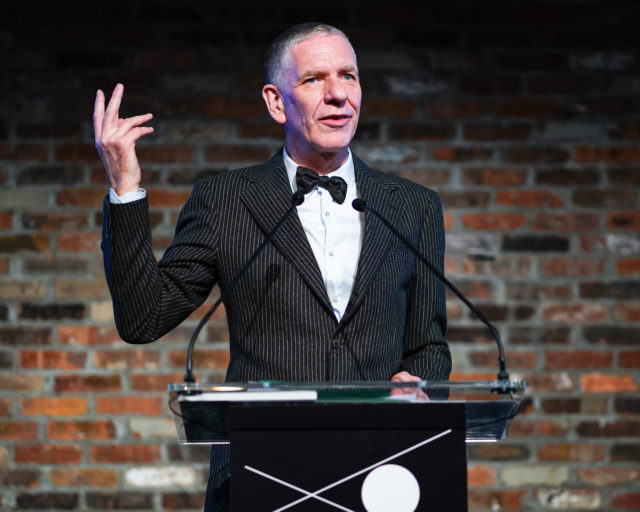

Zoe Leonard: Survey is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through June 10, 2018.