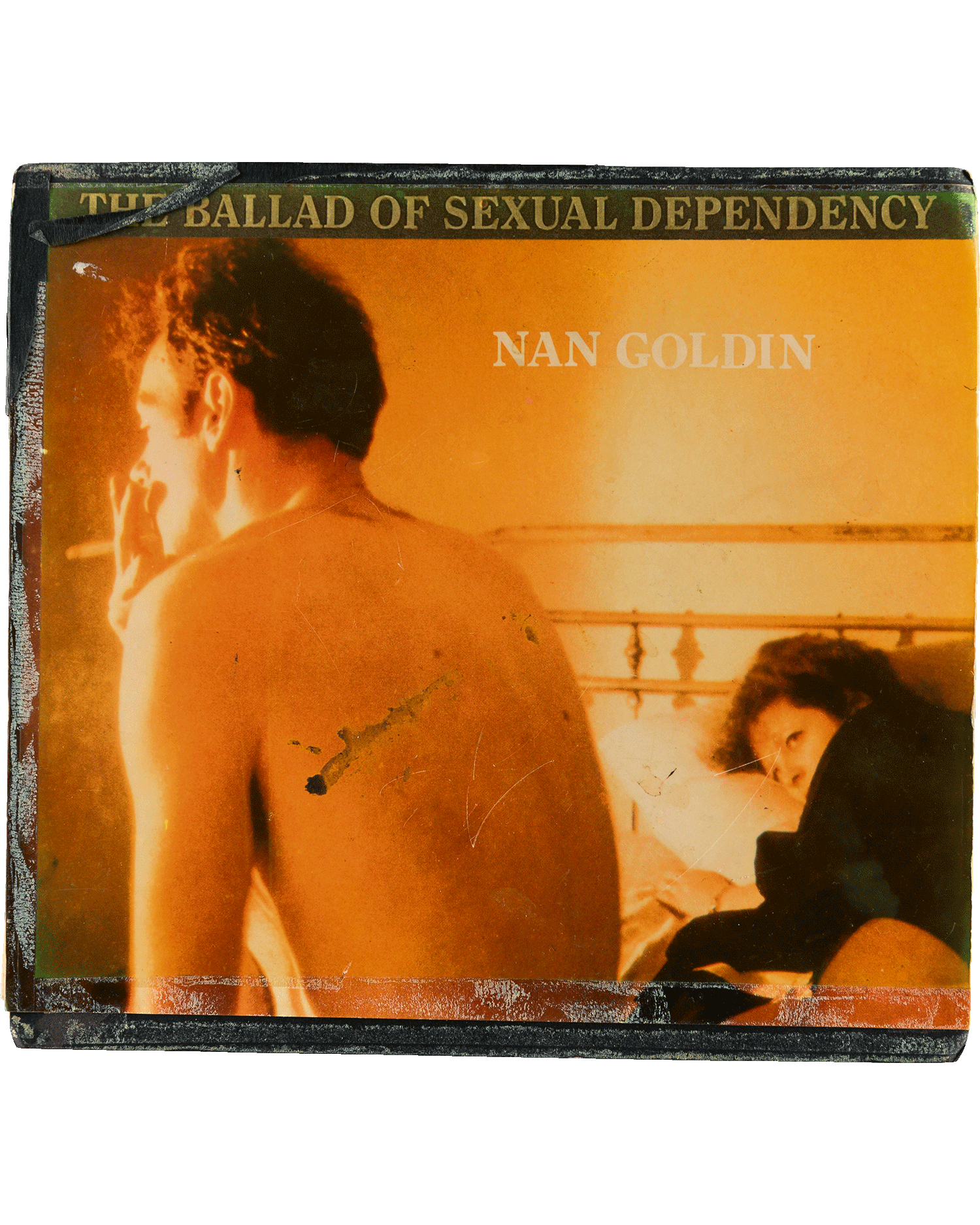

Cover of the original maquette of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, ca. 1985

Courtesy Nan Goldin

How did Nan Goldin’s slideshow with hundreds of images, presented at bars and nightclubs, become an iconic photobook? Elle Pérez speaks with the curator and editor Marvin Heiferman about the making of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.

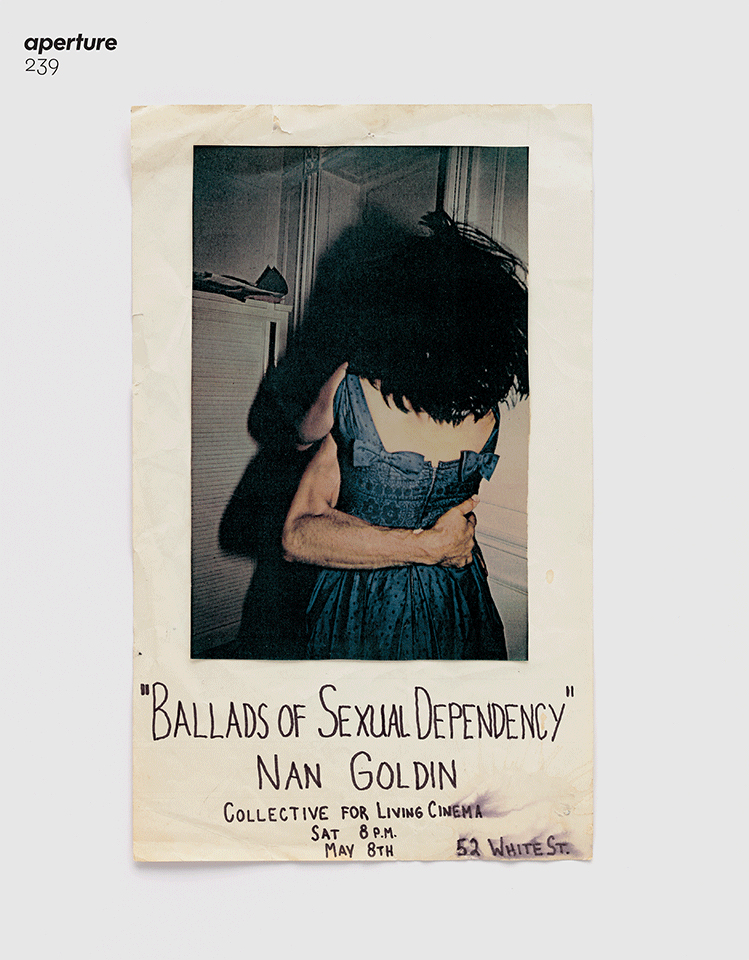

Courtesy Nan Goldin

Elle Pérez: I teach The Ballad every semester. And I create this fake slideshow for my students. I’ve scanned the entirety of the book. We put it up on the screen, and we play it in the dark, and I use a playlist for the music.

Marvin Heiferman: Oh, you kind of re-create it. That’s hilarious.

Pérez: It goes from Maria Callas to James Brown, and then—what’s that one song that’s like, “Kiss the girl” … ?

Heiferman: “Miss the Girl.”

Pérez: Yes. So we sit there for forty-five minutes and watch it.

Heiferman: The Ballad as a slideshow is so different from the experience of The Ballad as a book. Part of it is the power of the audio and the sort of trance state you get pulled into when you watch it, and listen to it.

Pérez: The color washes over you in such a different way than when you’re looking at it in the book. When it’s illuminated on a screen, you feel like you’re watching something that has to do with the sequence of the book, which is very romantic.

Heiferman: Romance is not a bad word to use. That’s certainly part of the allure of The Ballad. I don’t look at the book all that often, because I know it all too well. But looking at this new edition, it’s truer to the color and the experience of Nan’s slides in terms of that richness, which has a lot to do with what it takes to move people through The Ballad as a slideshow and as a book.

Pérez: How did you get involved in working with Nan? How did you even meet?

Heiferman: I was working at Castelli Graphics and running the photography program there. On the one hand, I was working with people like Lewis Baltz, Robert Adams, John Gossage, Ralph Gibson, and Mary Ellen Mark. And on the other, I was continually trying to open up the program and look at different ways photography functioned. I worked on Ed Ruscha shows, Andy Warhol shows, and Robert Rauschenberg shows. Marian Goodman’s print publishing business and gallery, Multiples, was around the corner, so I got to meet people like John Baldessari. My boyfriend at the time was in the Whitney Independent Study Program, and through him I met the whole Pictures Generation crowd. I was lucky enough to beat Castelli when multiple image worlds were kind of colliding with one another: modernist photography, the artist-using-photography thing, the Pictures thing, the rise of conceptual photography. Even though the gallery represented a specific group of people, I kept looking at work and kept trying to bridge all those perspectives in many of the projects I did.

One day, I think it was in 1978, I got a phone call from a person who said, “Joel Meyerowitz told me to call you up and show you my work.” It was Nan, and she was still living in Boston. So we made a date, and when the time came, Nan walked up the dramatic red-carpeted spiral staircase in the Upper East Side brownstone where the Castelli Gallery was located with a box of about twenty-five prints under her arm. They were fucked-up prints, with weird and oversaturated color, kind of messy prints, and some were signed “Nancy Goldin” in tiny, tiny handwriting. I looked at them, and I thought they were fantastic. I could tell what she was doing right off the bat, knew nobody else was doing anything like it, and I said, “Bring some more stuff back.”

When she showed up again, it was with a crate full of pictures, scores of them, which we went through. They confirmed to me that what Nan was up to was phenomenal. There was nothing like it. It was clear as day.

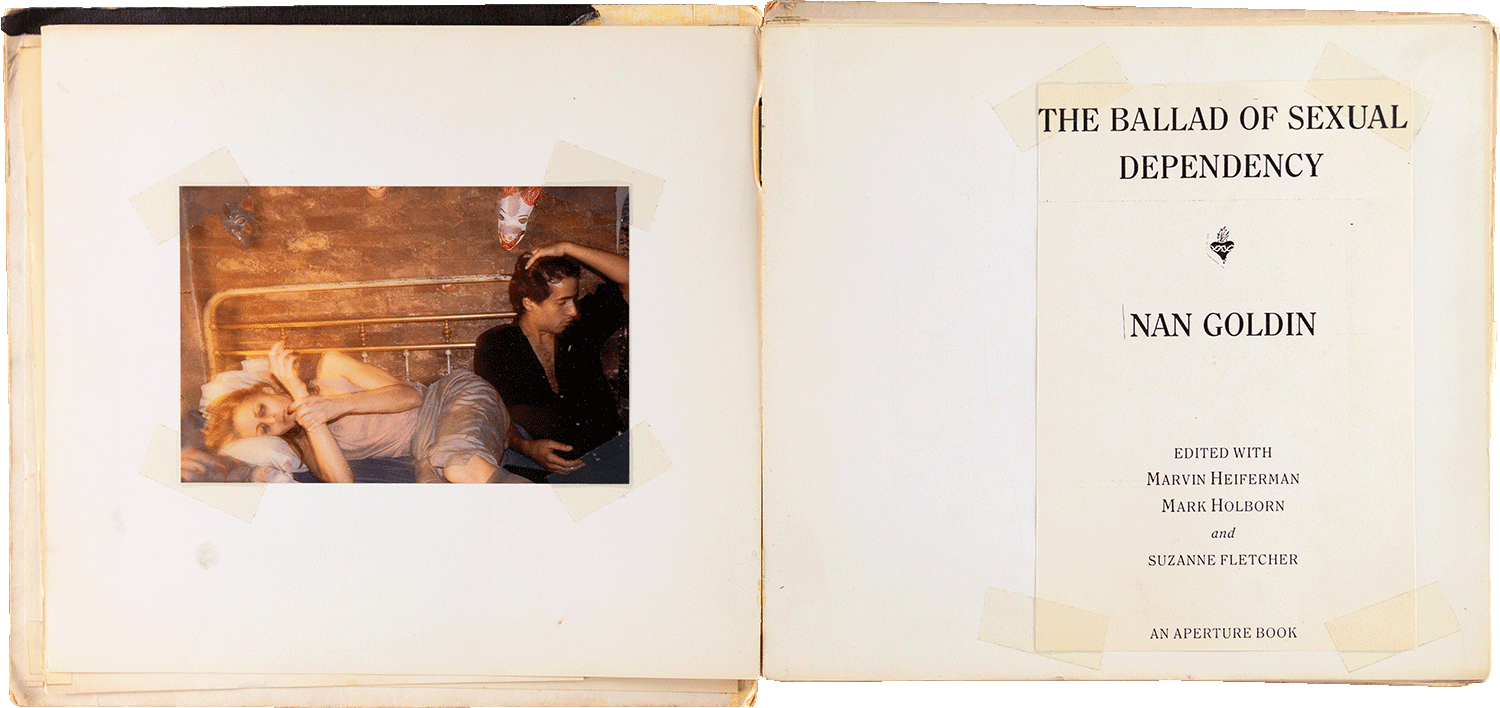

Courtesy Nan Goldin

Pérez: What did you see?

Heiferman: Pictures about relationships. This was a time when color photography was just starting to gain credibility in some people’s minds—and here were these pictures that looked and felt much more intense than anything that anybody else was doing. Even though Larry Clark’s Tulsa (1971) was already out in the world, Nan’s work looked explosive, too, but different. The pictures were just full of emotion, full of color, full of love. What struck me was what an incredible picture maker she was, which often doesn’t get talked about.

Pérez: I totally agree. I’ve looked at them many, many times. The one of Cookie Mueller sitting at Tin Pan Alley [Cookie at Tin Pan Alley, New York City, 1983] is an incredibly well-constructed photograph.

Heiferman: Yes, and while the pictures were individually beautiful in a particular way, it was their cumulative impact that was overwhelming. Nobody was making that kind of work about people in complex, intimate relationships. Nobody was making those pictures about sex who wasn’t glamorizing or pathologizing it.

The work was clearly unique, so I said, “Okay, let’s try to do something with this.”

I wanted to do a show of Nan’s work, but the gallery didn’t want me to do it. Basically, Mrs. Castelli said she thought that Ellsworth Kelly would be horrified by the pictures. (I’m sure Ellsworth would have loved them.) Basically, I think she was afraid of them. And it was that kind of resistance that was a contributing factor to my leaving the gallery.

After I did, I worked with Nan from about 1981 until about 1988 or so, and during that period I helped get the work out into the world. By that time, I had a lot of contacts in the art and photography communities and kept showing people the work and raving about it. Around this time, Nan started to develop the slideshow format, and soon The Ballad began to evolve. It was different every time Nan showed it.

Pérez: You helped produce the slideshows?

Heiferman: Yes, we both worked to line up venues to show it, and I was around when she was editing the slideshow some of the time. That was an extraordinary part of the experience, because while photographers so often work toward distilling a concise body of work, here we were dealing with this expansive, evolving, public, performative, dramatic thing. Some images were always included in the slideshows, but new ones were introduced all the time. Sometimes the chaos of the slideshow coming together—and often in the moments right before we had to throw carousel trays full of slides into bags, get in a cab, and show up someplace and present it—was unbelievable.

Pérez: Where were you showing it?

Heiferman: We would show it at clubs and places like OP Screening Room, on Broadway, which no longer exists. There was a notorious showing at the Saint [a gay club in the East Village that was open from 1980 to 1988], which I thought was going to be the end of my life.

Pérez: What made it notorious?

Heiferman: Just keeping things on a schedule and showing up on time was always a challenge, and it almost didn’t happen that night. People don’t realize that before The Ballad got programmed, which was for the Whitney Biennial in 1985, it was different every time we showed up. And when we did, there would be just two projectors, side by side, the music would start, and Nan would clutch the remotes, one in each hand, and the show would begin.

Pérez: So she would run it.

Heiferman: Yes, and there could be glitches. Slides would get stuck. Projector bulbs would burn out. We had to switch out slide trays on cue and as seamlessly as possible. So every time, for me, was a little suspenseful. The Saint was amazing, because it was probably The Ballad’s biggest venue at that point. There were hundreds, a thousand, maybe more—I don’t know how many people were there. I thought we were never going to pull it off, that it was never going to happen. And then it did, and when it was over, the place exploded. What is still vivid in my mind is a bunch of us frantically sorting out slides on Nan’s light boxes in her loft on the Bowery, just blocks away from the club, still traying slides as the show was scheduled to begin. That was a very different experience from working on the book, which we laid out on the floor of my loft in the Garment District in a much calmer process.

Pérez: It went from hundreds of pictures to how many?

Heiferman: The book has 127. That was the big challenge. It was clear that Nan wanted to do a book and wanted it to be an Aperture book, because she had an appreciation for what they did, and she wanted to be part of that history. That kind of ambition was, I thought, terrific, but at that point Aperture had never done anything like The Ballad. For me, what I learned when I was working in the ’80s was that you’ve got to make your own opportunities. The way the photography world was set up at that time, it was stratified, conservative, and dominated largely by straight white guys. If you wanted to make friction or make a break, you had to figure out how to do it yourself.

But I knew I could, pretty easily, take the book project to Aperture because I knew a lot of people working there. I just wasn’t sure they’d bite. I think I showed it to Mark Holborn [an editor there] before I showed it to Michael Hoffman [the former director of Aperture], but when I showed the work to Michael and he said, “We’ll do it,” I thought, Whoa. Whoa, we did that.

Courtesy Nan Goldin

Pérez: But then how did you actually do it?

Heiferman: We realized we had to stick to the sequence that the index of songs lays out, which drives the narrative of the piece forward. But first we’d have to edit The Ballad down, get rid of what, six hundred pictures, 550 pictures. If you’re always shooting people in bed, you’re going to have two hundred pictures of people in bed. If you’re always looking in mirrors, there are going to be two hundred pictures of people looking in mirrors. And then, there were always the favorite pictures, the pictures that worked best and, on their own, that created their own worlds, that had their own integrity.

Pictures were spread out on the floor of my loft for a long time. Weeks maybe. Me and Nan, and Mark Holborn, some of the time, and Suzanne Fletcher, some of the time. Sequencing books is very much like making music. The goal is to make things flow, to get somebody both to look and to turn a page. That was the challenge—to get rid of the extraneous stuff, keep the pictures we couldn’t live without, and then keep cutting from there.

Pérez: Were there a few that became the anchor points for the book?

Heiferman: The cover picture. The picture of Nan’s face battered. Some of the sex pictures. The drug pictures. The party pictures. Everybody’s got their own favorites. The Hug (1980) is one of mine.

When I was looking through the book earlier today, something I was struck by, and I’m sure we were conscious of, is the way the book moves from horizontal pictures to vertical pictures, from indoors to outdoors. There’s also the relationship between people looking at the camera versus people looking off to the sides of the frames, which Nan does consistently enough that it becomes an element in sequencing, too. You’re being directed. There’s the narrative. It’s like: Who are these people? What’s happening to them? What’s their relationship to one another? There’s the lush color that runs through the book. There’s the emotional roller coaster that takes you from pictures at parties and of people laughing, to pictures of people crying, and that hooks you. People have called The Ballad “operatic” and for good reason, because its grand scale and expressiveness sweep you along with it.

Pérez: Did you know it was going to be an important work?

Heiferman: Yeah. But it took ten years of convincing people. Because photography was still a confusing thing to people.

Pérez: It’s still this confusing thing to many people. It seems a little more accepted now, but I feel like people are still not sure to this day.

Heiferman: We’re still having that conversation, which is ridiculous to us.

Pérez: But we’re in.

Heiferman: Right, we’re in.

When we made the book, one of the challenges was getting model releases from people, which was dicey at times. I remember when Aperture asked, “Do you have model releases for everyone?” and I said, “No.” Something else I remember vividly is going down to the East Village to try to get hold of Brian, Nan’s ex, and get him to sign one and standing on the street, screaming up to his window, trying to cajole him to come down so I could give him a model release to sign—which never happened.

Pérez: And what about the text for the book?

Heiferman: The text that Nan wrote was the only text in the book. It didn’t dawn on us to go get somebody to write an essay for this book, to try to explain this book to the world. The difference between Nan’s text and the kind of postscript text in the back of the recent edition is interesting to see, too. It underscores that Nan always knew what she was doing.

Pérez: She writes, “I don’t ever want to lose the real memory of anyone again.” There is something about that “real memory” that is related to how visceral the book is.

Heiferman: The work’s intensity and authenticity were, and still are, palpable. It’s interesting now, in an Instagram world where everybody is projecting and branding themselves and figuring out how to represent themselves, that what Nan was doing was representing, but with a different set of criteria, a different set of brackets, a different kind of goal in mind.

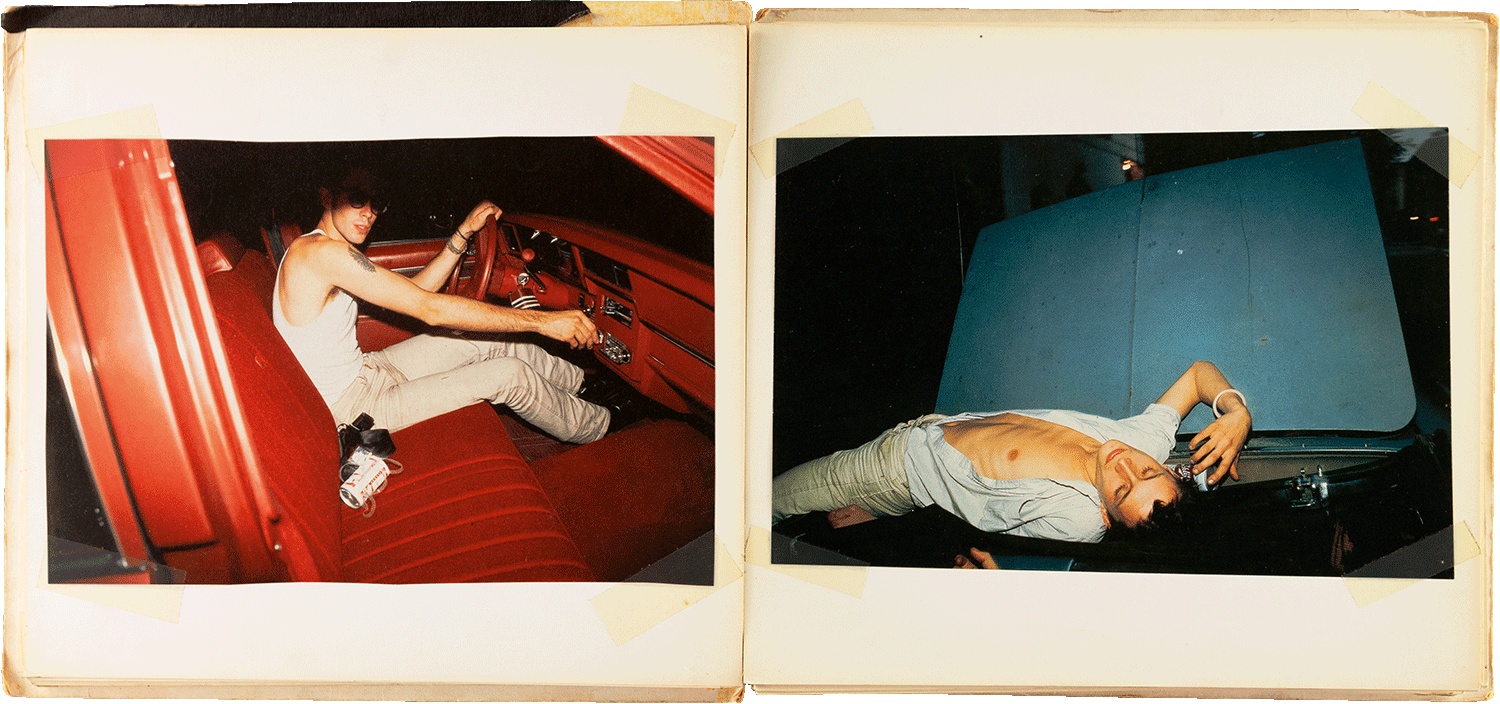

Courtesy Nan Goldin

Pérez: Totally. I think people in general are struggling with the claim that the camera can take control over a person’s own image. But, then, simultaneously, there’s a paradox, where people are very nervous now to use the camera to stake a claim.

Heiferman: You’ve got to take responsibility for yourself, the way you see yourself, and the way you see the world. That’s a tantalizing and scary thing, but that’s what identifies people as artists. Right?

Pérez: That’s a pull quote right there.

Heiferman: You want to see the world through somebody else’s mind or eyes, and Nan lets you do just that. It’s not that she wasn’t influenced by work that came before her. She was, and she knows it, and she has said it—and who wouldn’t be? Nan studied photography enough to know stuff. But what came out was something else.

The process of shooting all the time, which Nan did back then, gave her the option of constantly reediting the work and changing it. The kind of fluidity that the work documents, just on a process level, is also what it represents in terms of people’s lives—the fluidity of those lives. That’s another reason why the slideshow format was kind of perfect. And what makes the book so different is that it freezes The Ballad because people have such respect for and have put so much faith in books, where they experience pictures differently and privately. There was not a lot of opportunity to see The Ballad unless you were in New York, Berlin, Paris, or wherever it played. And there’s still not much opportunity to see it, because it’s such a big deal to mount it and dedicate viewing space to it. Back then, what was extraordinary was the experience of the slideshow, of seeing it in a club where everybody’s drunk and stoned, or at least lots of them are, and a good number of them are also in the pictures and are screaming when they see themselves on-screen.

Pérez: That’s amazing.

Heiferman: There’s also the difference of seeing a version of The Ballad when it’s the actual slides that are being projected, when you hear the clunking sound of them advancing in an irregular rhythm against the beats in the music, versus the experience of the digitized, smoother, synched-up versions where everything runs smoothly. No matter what, though, The Ballad works. Every time you see it, it’s different, because there’s so much to process and take in. And, for me, watching it is still a very personal thing, I just tear up. I remember all the stuff that went into it, my closeness to it, and, of course,

I can’t escape the theme of loss—that plays such a big role in it.

Pérez: That’s why I put such an emphasis on actually showing my ghetto version of the slideshow to my students. There’s something about the participation of it, too.

People always have these fantasies of bohemias, art worlds, and these communities of people. In fact, people create their own communities to support the work they’re doing—and here people got to see it celebrated in this kind of glamorous way.

Heiferman: That’s another quality of the work that’s wild. It is, in its own way, glamorous. You get to see this subculture that, for want of a better term, got turned into something cinematic. It’s a word that people tend to use a lot, but in this case the work really is. Nan always said she wanted to be a filmmaker, and I think that was always in her mind; she was always taking so many pictures. It was kind of like [Eadweard] Muybridge. She was both living life and capturing it in stop-motion.

Pérez: The other thing I’m thinking about right now is the relationship of this book to a book like The Americans (1958). That was something like twenty thousand photographs edited down to eighty-three pictures—how do you even reduce that? The Ballad went from some unknown number of photographs to eight hundred pictures. How many pictures do you need to make eight hundred good pictures? And then, to bring that down to 127. They’re both epics, in a way.

Heiferman: Look at Robert Frank and his move to video. Nan has made videos, too. I think there’s this recognition of both the power of individual images or images in a group, and the limitations of them.

Anybody who is making images a lot, and seriously, is going to grapple with that.

Pérez: When I first started making pictures, they were for all the punks up in the Bronx. I would put them up online, and then everybody the next day would look, and I would get immediate feedback. There’s something in the validation of showing things to your community first.

Heiferman: But then to be able to come up with work and narratives that reach beyond that audience is the interesting thing. As you were talking about putting stuff up online, I just kept thinking about Instagram. People’s Instagram feeds are their versions of The Ballad. How many pictures do you tell your story in? It’s an ever-evolving process. There’s a self-consciousness to that and, as The Ballad proved, a good reason to rely on photography to figure out who you’ve been and who you are going to be.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 239, “Ballads.”