Glamour and Destitution in Los Angeles

In his first museum retrospective, Anthony Hernandez finds melancholy beauty in a city of contrasts.

Anthony Hernandez, Discarded #50, 2014

© and courtesy the artist

The paradoxes of Los Angeles, its polarities between glamour and destitution, are not lost on Anthony Hernandez. Since the late 1960s, Hernandez has revealed, with formal integrity and bleak beauty, the harsh realities of his Southern California environs. His retrospective at SFMOMA derives its power from an unerring eye. A native of East LA, Hernandez has been less widely known than other California photographers—he met peer Lewis Baltz in the early 1970s—but this survey makes for a satisfying and timely look at an artist whose innovations are subtle yet significant riffs on key themes in contemporary photography.

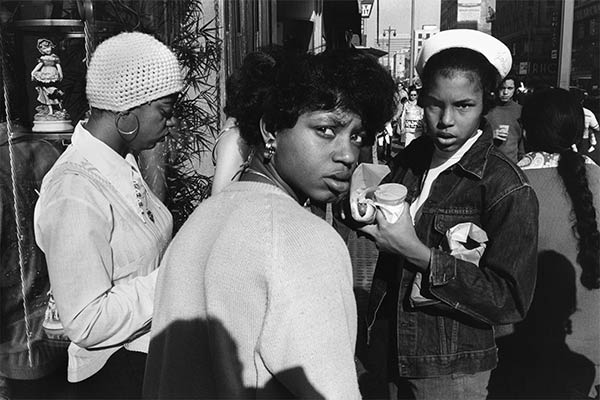

Anthony Hernandez, Los Angeles #14, 1973

© and courtesy the artist

The bodies of work on view, ranging from early figurative works to forms of landscape and still life, together form a dour, formally impressive vision that frequently achieves a quiet balance between aesthetic and social concerns. The exhibition initially draws an apt connection to street photography traditions, and the catalog notes that Hernandez met Garry Winogrand in the late 1970s when the elder photographer lived in LA. In the 2013 Winogrand retrospective, also at SFMOMA, Winogrand’s photographs of Los Angeles contained a profound sense of melancholy. In contrast to his pictures of the vibrant sidewalk culture of New York, Winogrand’s LA work reveals a place where those without automobiles are stranded on wide, otherwise empty sidewalks, and in failed Hollywood aspiration.

Anthony Hernandez, Santa Monica #14, 1970

© and courtesy the artist

Similarly, the first powerful iteration of Hernandez’s vision is a 1969–70 series of black-and-white beach photographs that depict sleeping figures adrift on fields of sand—a form of prostrate street photography. Most of the subjects are fully clothed, as though the beach is a safe site to nap, when necessary. In Santa Monica #3 (1970), a male figure seems to be destitute, crawling through the desert with paralyzed legs. In another, even sunbathers appear troubled: bikini-clad women are isolated from their environment and strangely exposed.

Anthony Hernandez, Rodeo Drive #3, 1984

© and courtesy the artist

Nearby is Hernandez’s first foray into color—which became his signature mode—a 1984 series of photographs shot on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills. The tony setting, with pops of red and gold, poses a striking contrast to the beach pictures, heightened by the camp factor of ’80s fashion. Still, the figures exude an existential hollowness; they are people slipped into an empty but overpriced lifestyle. Even if their hair is teased to mercilessly comic effect, the success of these pictures is in their cool humanity.

Anthony Hernandez, Forever #74, 2011

© the artist and courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

The show then backtracks chronologically to Hernandez’s transitional work in black and white. These photographs, in a section titled Absence and Presence (1978–1990), were shot with a large format camera and depict the vastness of the Southern California landscape. In content and style, they relate to the “New Topographics,” the term that coalesced around a group of photographers including Robert Adams and Stephen Shore, who reimagined the postindustrial American landscape. Hernandez’s Public Transit Areas pictures, from 1979–80, reveal the isolation of Angelenos as they congregate at bus stops on wide, desolate, smoggy boulevards. There’s more formal innovation to two other late 1970s series, Automotive Landscapes and Public Fishing Areas, which show, respectively, rough and tumble car repair shops and prosaic recreation areas from a slightly elevated perspective atop Hernandez’s VW van.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless #1, 1988

© the artist and courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

The centerpiece is Hernandez’s Landscapes for the Homeless (1988–91), a powerful group of images that capture makeshift domesticity in wooded areas devoid of their inhabitants, who have seemingly gone about their daily business, and left their “homes” vulnerable. There’s a palpable sense of trespassing upon a private space, but it’s a revelation to see a vast pit of cigarette butts surrounding a rumpled blanket, or brushes and combs laid carefully on a plastic bag on the dirt. In its drive to consider urban planning and social observation, Landscapes for the Homeless anticipates such practices as the Center for Land Use Interpretation.

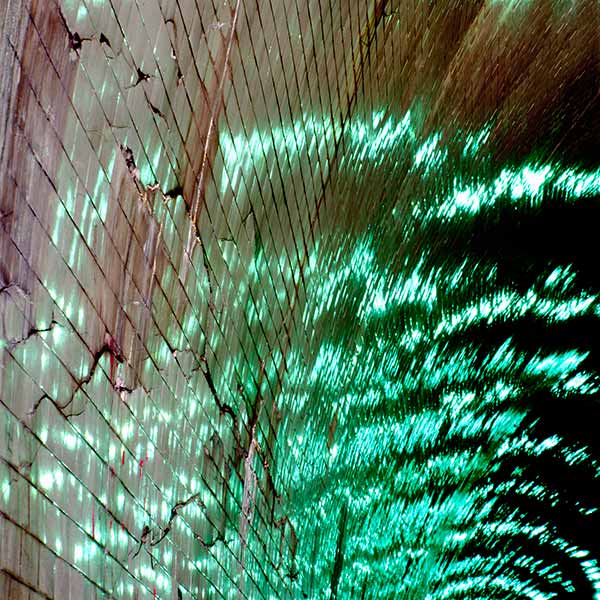

Anthony Hernandez, Pictures for Rome #17, 1999

© and courtesy the artist

Hernandez’s late-’90s work, set in abandoned buildings in Oakland, Rome, and Baltimore, and along the Los Angles river, become more abstract visions of locations buffeted by economic conditions—stalled construction sites, and abandoned buildings and sewage culverts. These photographs are less immediate but more poetic in their power. They provide evidence of beauty within fraught locations—a view from a homeless person’s bed, for example—though the aesthetic value of such a perspective seems as difficult to parse as redressing the social condition. Taken together in the sweep of this exhibition, Hernandez’s persistent vision rewards with its resolve.

Anthony Hernandez is on view at SFMOMA through January 1, 2017.