How a No-Frills Zine Transformed a British Town

From Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019

Courtesy the artist

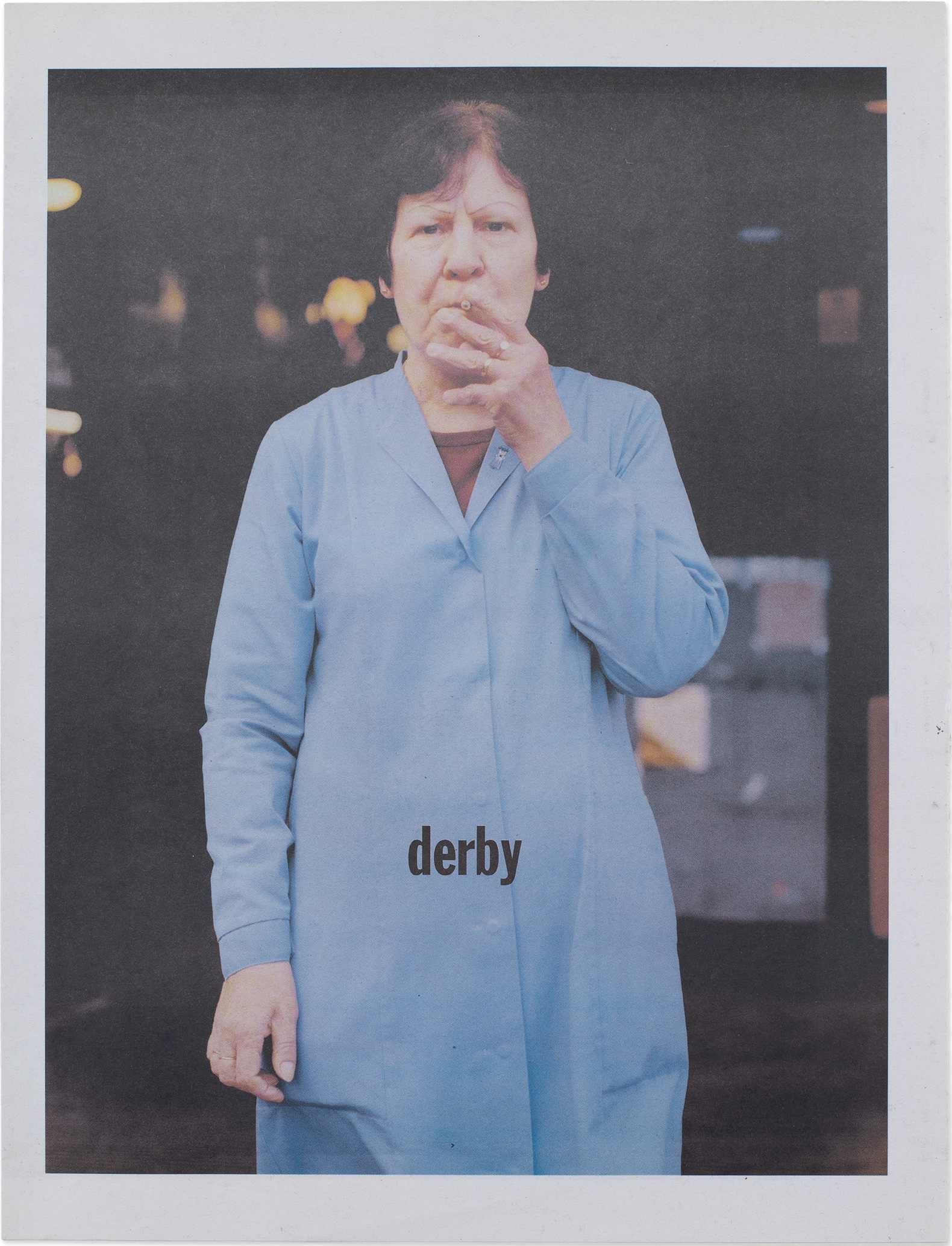

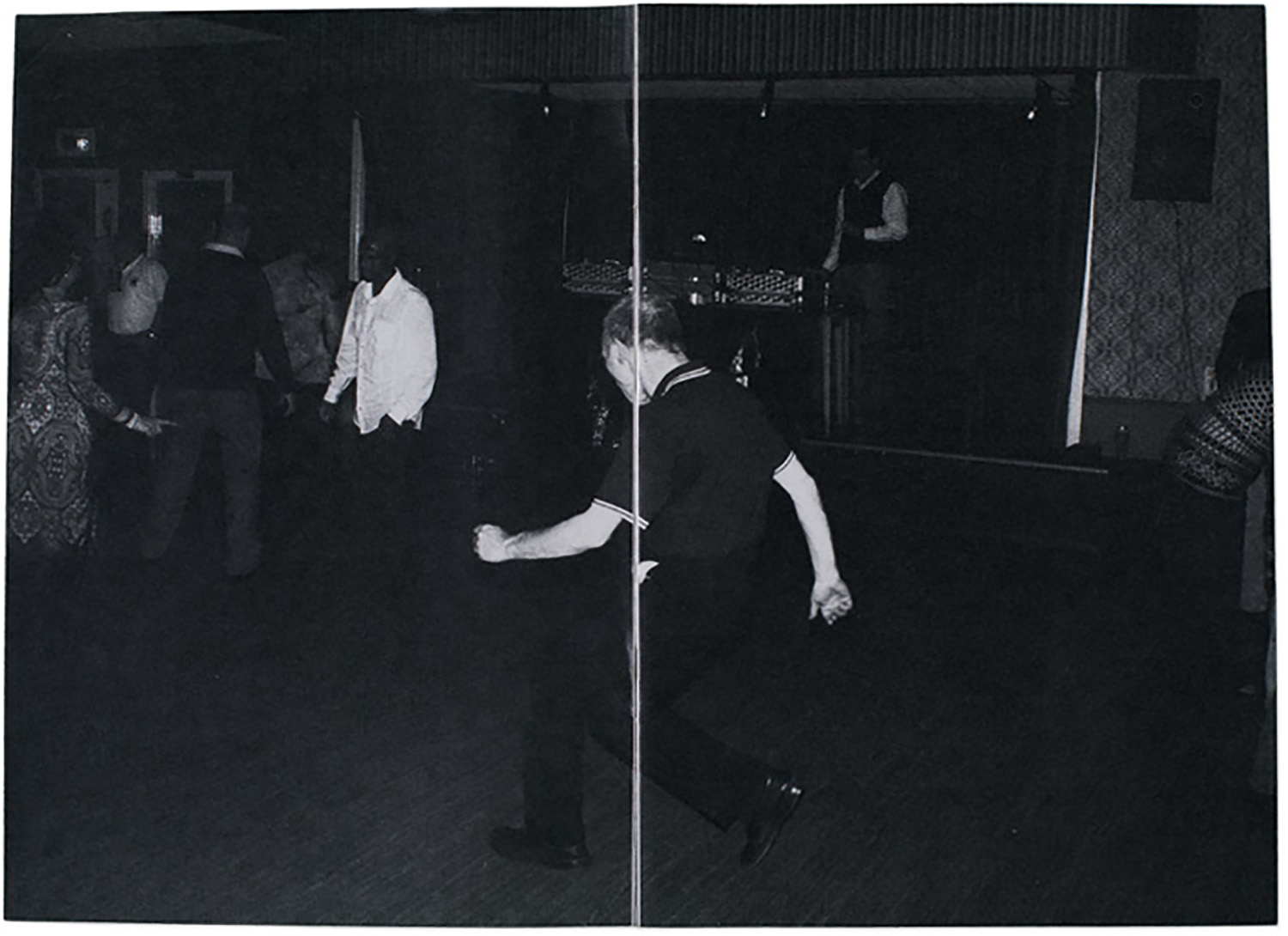

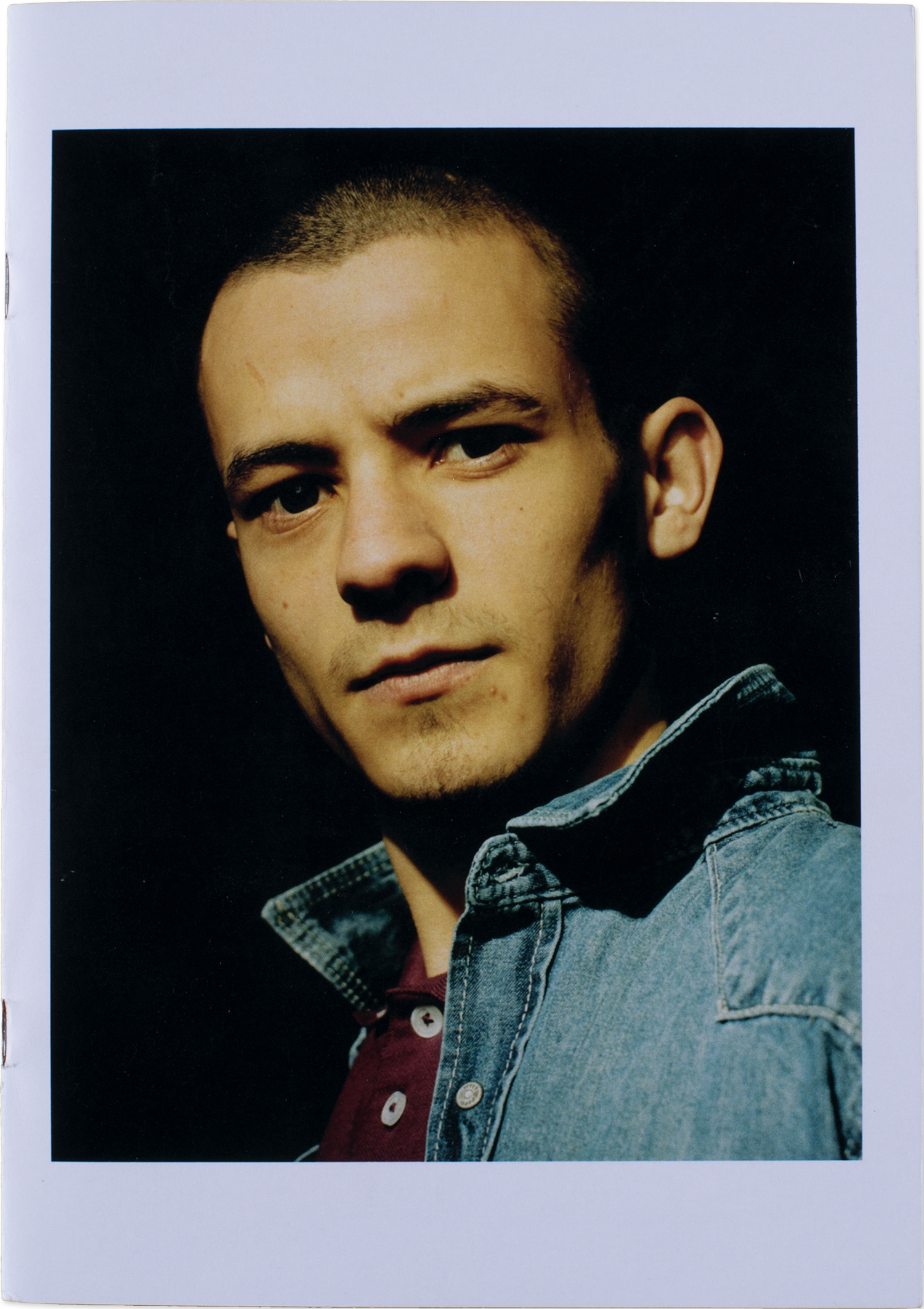

Britain’s ubiquitous graffiti-strewn carparks, rundown bus stations, and no-frills pubs might not seem like obvious subjects for artistic scrutiny. But these seemingly innocuous places hold a special kind of magic for Adam Murray and Robert Parkinson, who started documenting them a decade ago in Preston, the northern city where both artists lived and worked at the time. Now, the pair looks over the legacy of their collaborative project with a new book, Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019, presenting a slice of the huge amount of imagery they produced.

Murray and Parkinson met through University of Central Lancashire and quickly struck up a friendship through a mutual interest in photography, identifying the city’s relative lack of visual culture—particularly compared to its music and nightlife scenes. To fill this gap, they began producing a modest black-and-white, hand-stapled zine called Preston is my Paris as a way of celebrating largely overlooked areas of the city and the people that populate them (Murray is now a lecturer at Central Saint Martins and Manchester Metropolitan University; Parkinson still mainly works as a photographer). This DIY approach included new and found photos and random bits of ephemera, collated with little editorial intervention, along with modest distribution that consisted of handing the zines out for free.

From Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019

Courtesy the artist

“It was pretty simple, there wasn’t much concept—it was just for fun!” says Parkinson, who had no background in photography and only began shooting at Murray’s suggestion. “I picked up a camera two weeks after I graduated,” he adds, “and my first roll of film was in the first zine. We learned as we went along—simple things, like the fact you need multiples of four pages. We would print out a mock-up and everything would be out of sync. We had no idea about those things.”

This small-scale project—with a self-effacing title that Murray describes as “nicked off of a Clarks shoes advert that made British cities look like exotic places”—grew a local following, thanks largely to conversations initiated by the pair as they traversed the city looking for people and places to photograph, from young clubbers to older couples like Iris and John, who were snapped following a jovial chat in the pub. “It was a form of hyperlocal social media, because people would pick up the zine to see if they or anyone they recognized was in it,” Parkinson explains.

From Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019

Courtesy the artist

Murray and Parkinson’s self-published labors of love stand out because they are born out of two individuals who really understand the city that they live in. Their celebratory approach, with plenty of subjects actively embracing the presence of the camera, eludes any sense of voyeurism; it is unselfconscious and self-assured in a way that only comes from being comfortable in your environment—and perhaps a little bit naïve. In fact, Parkinson says that he is amazed by some of the images that he made with such a fresh eye, which can be hard to replicate “once you have trained yourself out of it.”

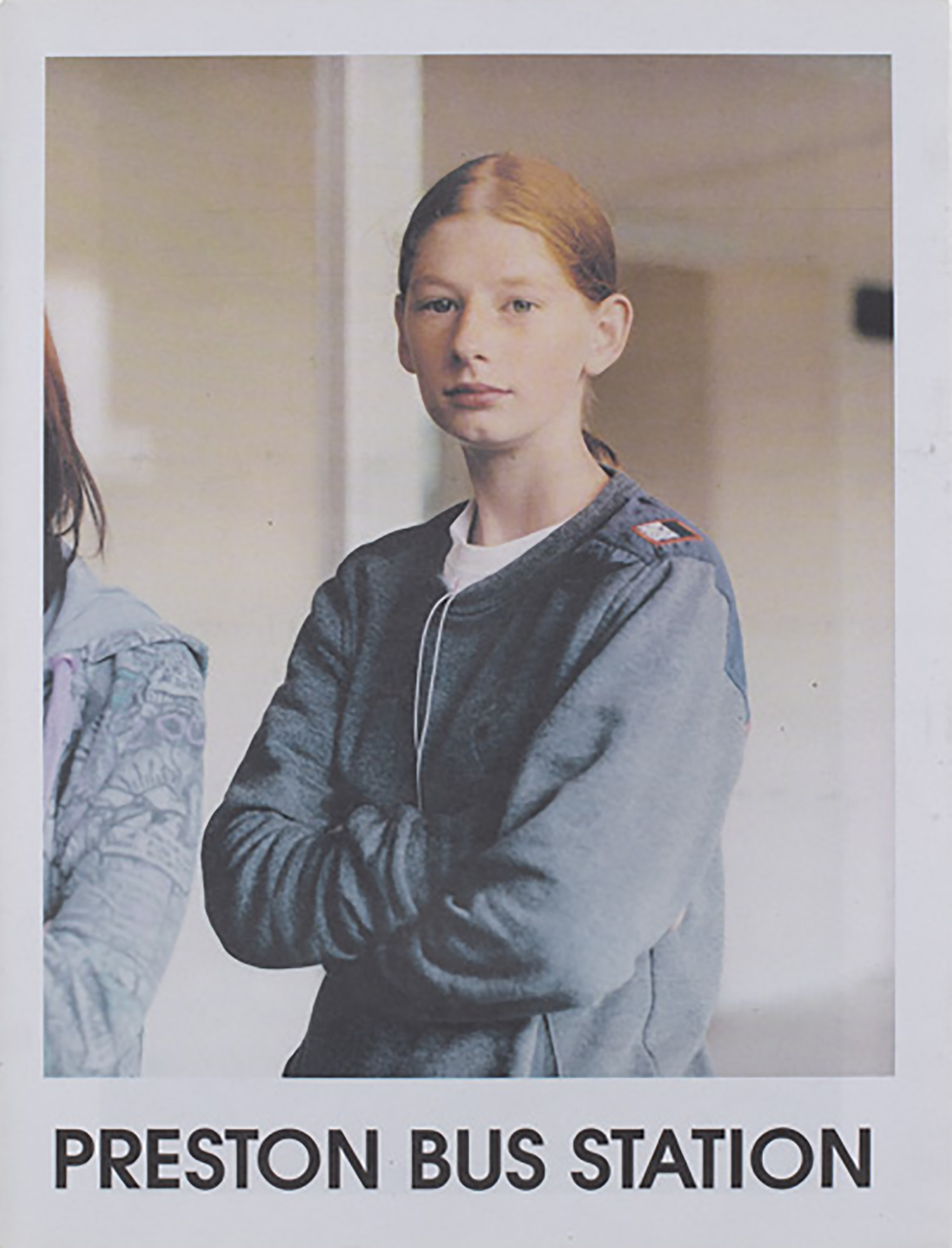

As the zine gained traction, so did new opportunities for Preston is my Paris to become a full-fledged imprint. Within their first year of publication, Murray and Parkinson mounted an exhibition in a disused shop, holding workshops and a pop-up portrait studio and relying on local foot traffic to get the message out. They also produced a newspaper showcasing the work of photographer Jamie Hawkesworth, whose images of Preston Bus Station celebrate its Brutalist architecture and the people who travel through it every day in alluring, saturated hues. Printing a paper both allowed for full color and was a format that many in the local community were familiar with and might be more likely to pick up. “It all comes back to understanding the city and how people might engage with what you’re doing,” says Murray. “In Preston, it is not necessarily on the top of people’s priority list to seek out art and culture, but that doesn’t mean they are not interested.”

From Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019

Courtesy the artist

As far as Parkinson is concerned, Preston is my Paris—a project that has gone on to produce over forty books and numerous commissions around the world—is a far cry from the platitudes that are so often offered by museums and cultural institutions in an effort to appear locally relevant. “There’s lots of talk of ‘socially engaged’ photography, which comes across as a bit elitist,” he says, “because when you think about it, that is what all people-focused photography is. If you’re taking their photos, you’re meeting them, talking to them, and getting their stories.”

The anniversary book reflects this outlook. “We had so much material,” says Murray. “But a lot of people haven’t seen the work, so we wanted to produce an edited portfolio of images, and also include our wider reflections on the project.” As a result, they invited a range of individuals to include their thoughts on Preston is my Paris and its legacy, including Jamie Hawkesworth (whose photos are featured) and Iris Lunt, who became a subject after she met the pair in her local pub. While their personal accounts exemplify the intimate, friendly atmosphere that Preston is my Paris fostered, City Council Leader Matthew Brown takes a broader view, commenting on the zine’s ability to capture “the reality of life in our city at that time,” as well as the changes the area has endured over the last decade.

From Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019

Courtesy the artist

For Murray and Parkinson, the new publication offers a chance to look back, but also to gain new audiences, who will hopefully feel inspired by the project. “One of the main purposes was to encourage people in Preston to do more. They might like what we’ve done or hate it, but either way, the hope was that it would encourage them to do their own thing,” says Murray. Parkinson echoes this sentiment: “We want people to really see the area. There’s something interesting in any town in Britain, you’ve just got to find it.”

Adam Murray and Robert Parkinson’s Preston is my Paris: 2009–2019 was published by Dashwood Books in November 2019. More information about the project can be found on the Preston is my Paris website.