Envisioning the Right to Vote

Coinciding with Aperture magazine’s “Vision & Justice” issue, students in Sarah Lewis’s Harvard University class “Vision & Justice: The Art of Citizenship” contributed essays on the relationship between images of social unrest and landmark Supreme Court decisions. Here, Jonathan Karp reflects on Bruce Davidson and voter ID laws.

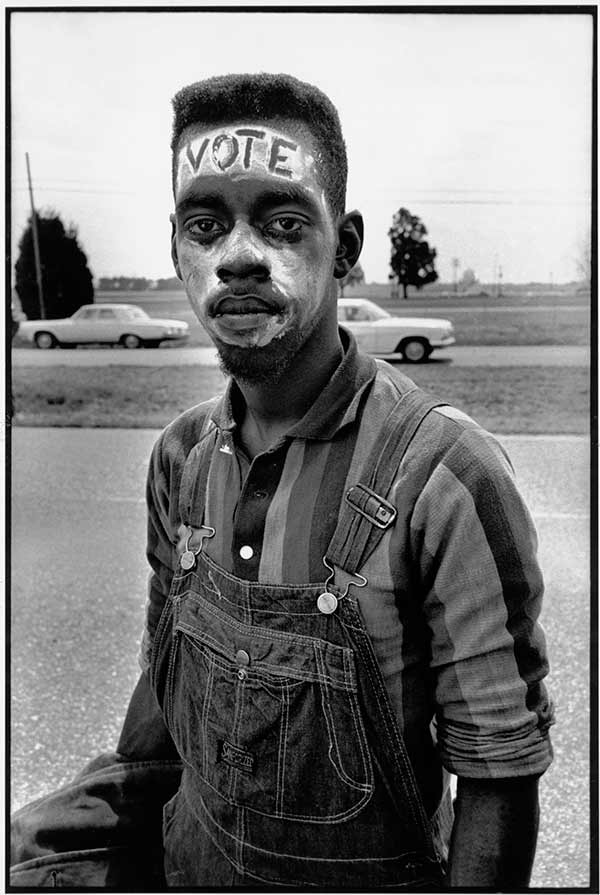

Bruce Davidson, Young man with “Vote” painted on his forehead walking in the Selma March, 1965

© Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Somewhere between Selma and Montgomery, in the first days of spring 1965, Bruce Davidson took a photograph of a young black marcher. The young man’s name is not recorded, but he appears in several of Davidson’s photographs of the march from Selma to Alabama’s capital. It’s no mystery why. The young man’s painted face illustrates the fight for voting rights in literal, stark relief: “VOTE.” The word is his skin, his blackness. Whiteness, in the photo and in the United States, is required for both the word’s legibility and the citizenship it represents.

In other photographs, the young man moves. He marches, eyes forward and fixed beyond the frame, his mouth open in mid-chant. The sound and action of these photographs makes the “Vote” photograph seem still in equal measure. Here, the young man looks directly at the photographer’s lens. Although Davidson was working in the context of documentary photography, the angle of his subject’s torso and his direct gaze places the image in the tradition of portraiture. It’s the combination of this formal stillness, the provocative face paint, and the context of the civil rights movement, which, paradoxically, suggests a relationship between the photograph and a Supreme Court case that would be decided fifty-three years after it was taken. In fact, Davidson’s photograph finds its echo in the modern debate on photo ID laws.

Crawford v. Marion County Election Board, decided in 2008, holds that an Indiana law requiring voters to show photo identification does not violate the Constitution. Though voter ID laws have existed in the United States since 1950, Indiana was among the first states to require photo IDs specifically. These laws serve to discourage or outright prevent those without photo IDs—a disproportionate number of whom are African American—from voting. What does it mean for the state to require a portrait in exchange for exercising one’s rights as a citizen? In this context, Davidson’s photograph reveals how photo IDs are merely the latest visual site where ideas of race, citizenship, and justice collide.

ID photographs are a form of portraiture, but also the portrait’s fraternal twin, the “type,” which establishes norms and compares subjects against those norms. Through a scientific gaze as dispassionate as any at the DMV, nineteenth-century types codified racial difference and justified racism. Photo IDs, as a contemporary type, are similarly relied upon for their accuracy, their ability to classify, and their existence as proof of citizenship.

In the spring of 1965, a young man marched to claim his rights. A half-century later, his image might now exist in a state archive, allowing him, in some states, to vote. A century earlier, his image might have entered an archive and marked him as subhuman. These multiple visions mark the end of slavery, the maintenance of state power, and the uninterrupted life of photography as an apparatus with which black Americans must negotiate their humanity and their citizenship.

Jonathan Karp studies race, protest, and performance in Harvard University’s Ph.D. program in American Studies.