The Provoke Moment

In the first of an ongoing series of interviews about Japanese photography with Tsuyoshi Ito, Curator Simon Baker discusses the radical new vision of the 1960s.

Provoke was founded in Tokyo in 1968 by Daido Moriyama, Takuma Nakahira, Takahiko Okada, Yutaka Takanashi, and Koji Taki. The magazine examined Japan’s socio-political situation with a radically inventive style. Although only three issues were published, the publication’s impact would prove to be profound, revolutionizing photography inside and outside Japan. Today, the influence of the work published in its pages can still be seen in new generations of image-makers. This article is the first in a series of interviews about Japanese photography, produced in collaboration with A/fixed, a new publication geared to English-speaking audiences.

Director of the Japanese Photography Project, Tsuyoshi Ito spoke with Simon Baker, Senior Curator of Photography and International Art at London’s Tate Modern, about the legacy of the storied publication.

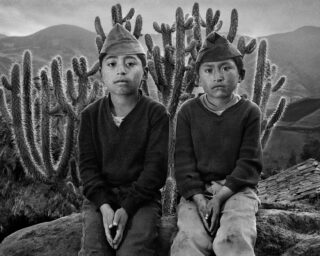

© Gen Nakahira and courtesy Osiris and Yossi Milo Gallery

Tsuyoshi Ito: How would you define or describe the photographers in Provoke?

Simon Baker: Often when people think of Provoke, they think of the magazine. They think of quite blurry, grainy shots of street-level photography. But actually it’s varied, and there are many different approaches even within one photographer’s work. Daido Moriyama, for example, had many different ways of making pictures at this time. If there is a unifying characteristic, it is an openness to chance, to experimentation, and to a radically different kind of photographic image—whether more like a screen print or a film still, an abstract painting, or however else we might think of it. It’s about being open to photography having different characteristics, potentials, and possibilities beyond the descriptive use of the photographic image.

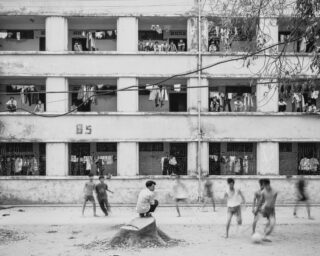

© Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Ito: Is there a particular image that you can think of, let’s say, of Daido Moriyama’s, that you have in mind?

Baker: Nakahira’s photobook For a Language to Come (1970) defined Provoke. Even the title suggests that there’s a new visual language that’s available. Nakahira is a great writer, somebody who’s interested in theory, and writing, and thinking about people like Walter Benjamin and Eugène Atget as well as previous generations of photography theorists. But really Nakahira’s aim with that book and title was to suggest a new visual language, a new way of describing one’s experience of the world. What marks out Provoke as avant-garde in the full sense, in the sense we might think of Surrealism, for example, is an attempt not only to make images, but to give a sense of the perspective from which the person making the images is seeing the world. So it’s about experience—how do we experience life in the world around us? In busy urban centers like Tokyo in the late 1960s and early 1970s, you are seeing, in the photography of Provoke, an account of lived experience, which is a very radical kind of image-making. It’s not photography as an objective, descriptive medium. It’s photography as an expressive, subjective, and quite radical medium.

© Gen Nakahira and courtesy Osiris and Yossi Milo Gallery

Ito: Can you put the Provoke photographers’ work in the context of what was happening in Japan at the time?

Baker: Well, the photographers associated with Provoke have very different politics. Moriyama, for example, always said that he was not particularly interested in politics. He photographed one student protest, but it wasn’t something that he was doing a lot of. Other members of the movement were engaged with not only student protests, but also with key social issues like the presence of American military bases. Miyako Ishiuchi made a lot of work, slightly later, about Yokosuka, where the American bases were located. And then there are big, pressing issues like the Narita Airport clearances and moving entire populations of people. There is a range of levels of engagement from the quite detached—viewing a world that was changing—to documenting specific protests and political issues. Rather than just the images that were in the magazine, the Provoke moment encompasses all of those different aspects.

© Gen Nakahira and courtesy Osiris and Yossi Milo Gallery

Ito: Can you relate their movement to what was happening in other parts of the world?

Baker: The global political upheavals around 1968 were happening in Europe and America (as well as in Japan) and were often student-led. There were demonstrations against the Vietnam War, a major issue that united people from different places in thinking about what American power meant. This had specific meaning in Japan. That global sense of urgent political issues united photographers. Remember that travel and the exchange of ideas were relatively limited. But you do certainly see exchanges of political concepts between Japanese photographers and those working elsewhere. There’s an amazing Provoke book about Che Guevara, for example, which is a very rare, very unusual book. It’s made by Japanese publishers and it keys into a kind of cause célèbre on the Left in Europe, in America, and indeed in Africa and the Caribbean.

© the artist and courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery Photography/Film

Ito: What kind of influence did Provoke have on photography inside and outside of Japan?

Baker: Soon after the Provoke moment, there were exhibitions of Japanese photography outside Japan. There was the famous New Japanese Photography exhibition at MoMA in 1974. It did not have much Provoke work in it, but included many of the photographers associated with that group. Outside of Japan, there’s a sense in the photography world that things are happening there. But beyond Moriyama, Shomei Tomatsu, and Eikoh Hosoe, many figures were not able to establish big, international careers. In the catalog for New Japanese Photography, Shoji Yamagishi (who organized the show with curator John Szarkowski), states that people outside of Japan need to understand that photography in Japan is about the series: it’s about groups of images; it’s about the book—and he said this in 1974. I think it has taken a long time for the rest of the world to learn that lesson and say, well, let’s not just focus on one famous image—Moriyama’s Stray Dog, Misawa, Aomori (1971) for example—but let’s try to understand where it came from, what the series was, how he was working, what he was doing. The same can be said of people like Yutaka Takanashi and Takuma Nakahira, whose work is now understood through the increasing interest in the photobook. The same goes for Miyako Ishiuchi.

But I think that sense of the breadth, depth, and complexity of Japanese photography has taken a long time to filter through to the rest of the world. Even with the most famous photographers, like Nobuyoshi Araki—we, outside Japan, know relatively little of what he was actually doing in relation to publishing. If you look at early Araki books, there is a lot of text and very little of that has ever been translated for non-Japanese reading audiences. There are some interesting issues in terms of the delays and the problems with creating a broader understanding.

© Gen Nakahira and courtesy Osiris and Yossi Milo Gallery

Ito: For people outside Japan, what is the fascination with Provoke, or about the people around that movement?

Baker: Well, there might be two things. On the one hand, the history of post-war photography for a long time was conceived of and delivered from quite an American-and European-centric point of view. If we think of the shift from William Eggleston and Stephen Shore to Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth, it gives a very particular view of what constituted progress, or what constituted something properly creative and avant-garde. But if you consider photography within its own avant-garde character, thinking about things like publishing and series, and the importance of connections to politics and other kinds of art forms, then Provoke seems like an interesting, alternative way of understanding the post-war period and the ’60s and ’70s. There is a cliché that 1972 was one of the best years for Conceptual art, but 1972 was also the year that Moriyama produced Farewell Photography and Hunter, so there are other ways of understanding that moment.

I think non-Japanese curators and historians and, indeed, collectors and critics, can see in Provoke something that they recognize as avant-garde, in that sense of Dada or Surrealism—a group of people working together, sharing ideas, pushing each other to more and more creative achievements. The people associated with Provoke were really investigating what photography could do as a medium, and that makes it really important. The radical potential of the photograph was pushed to these limits much more fully in Japan than in other places at the same time.

© the artist and courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery Photography/Film

Ito: Are there qualities or attributes that are unique to Japanese photography or to the time of Provoke?

Baker: Well, I wouldn’t ever distinguish things by geography and region. I don’t think that everything that was happening in Japan was unique, and I think some of things that were happening there were as a result of the Japanese photographers’ interest in, for example, William Klein—an American photographer based in France—or their exposure to Ed van der Elsken or Robert Frank. The interest in and the power of publishing in Japan was quite significant. Outside of Japan, there weren’t book designers of the same caliber as those working with Moriyama and Takanashi. Yutaka Takanashi’s Towards the City (1974) or Eikoh Hosoe and Tatsumi Hijikata’s Kamaitachi (1969) or Hosoe’s Ordeal by Roses (1961-62), are books that could not have been produced in any other context. That’s the history of the love of paper, of a particular kind of craftsmanship, skilled printing, which indeed are continued in the collotype workshop (at the Benrido Collotype Atelier in Kyoto). When you look at Japanese photobooks of the ’60s and ’70s today, they still look much more sophisticated than what was happening elsewhere.

A/fixed’s inaugural publication, Provoke Generation: Japanese Photography ’60s-’70s is due April 2017.