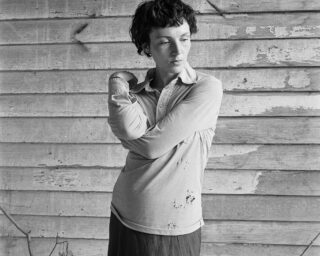

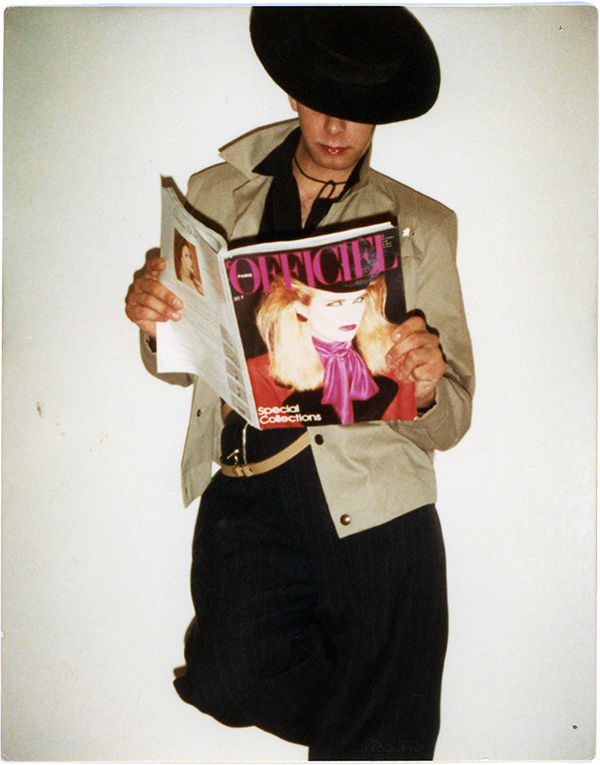

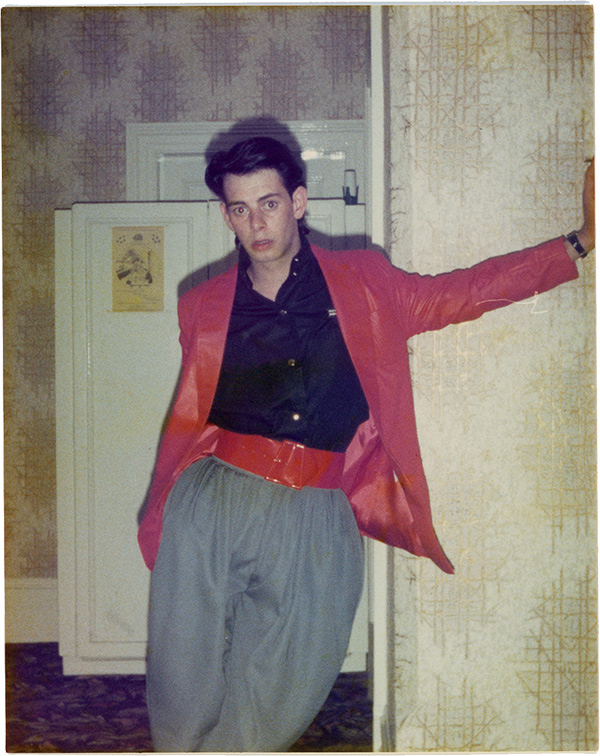

Untitled photograph, ca. 1977–84

Yvonne Taylor and her daughter Amelia Lonsdale are from Doncaster, a town in Yorkshire, northern England. I first encountered Taylor’s archive of photographs as a visiting lecturer at Leeds Arts University, where Amelia was studying photography. This personal archive consists of photographs predominantly featuring Yvonne and her partner at the time, Dennis Shedrick, produced while they were both living in the north east of England. The following are excerpts from a conversation I had with Amelia and Yvonne; I am currently working with them both to include the work in a group exhibition that I am curating with Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool, scheduled to open in spring 2020.

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Adam Murray: Can you explain the story behind this collection of photographs?

Yvonne Taylor: The photographs are from the period around 1977–84. At the time I was living in Doncaster, living at home with my mum in a mining village, and worked at Doncaster Council.

At the end of 1977 I started going out to Outlook Club in Doncaster, which on Monday nights featured different kinds of bands. This became a really important club in my life, as it changed the way I looked at fashion and music. The love of music and dance and fashion was what inspired me to start sourcing clothes that were different. At the time, there was no fashion shops like there is now—there was only things like C&A and Chelsea Girl. The main source of my clothes came from jumble sales, or from raiding my mum’s and my grandma’s wardrobe.

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: When did you first start becoming aware of the importance of photography to you?

Taylor: I don’t have a lot of photographs from the early days, because basically I didn’t own a camera. Not everybody had cameras of their own and we certainly didn’t take them with us when we went out. But something that did make me start thinking more about image and how you looked was the emergence of fanzines. I’d made friends with a lad called Stephen Singleton, from Sheffield, who was in a band at the time and later became part of ABC. He wrote a fanzine and used to put photographs in of his friends. They were all in black and white, just printed on a local printer. But it made us start to think about how we looked. We would be inspired by other people and how they looked in magazines, which were starting to documenting real people, not celebrities or film stars and pop stars that we’d seen in magazines before then.

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: What was your relationship with Dennis?

Taylor: I met Dennis in 1978, when punk was slowly dying and we needed something to take its place, and along came what is now called New Romantics. That was very fashion-focused; it was important to look different, to be as unique as possible, so I started making clothes. Sometimes I only adapted things, or changed the buttons or added a bit of fur to make it look different. We wanted to keep a record of that, so I bought Dennis a camera. Dennis was really into fashion and it was important to him how he looked, and he loved taking photographs of me. He liked to have photographs in his room of me. We didn’t live near each other—he lived in Scunthorpe, he worked on the steelworks, got grotty and dirty, came home, changed into somebody different, and it was documented in the photographs. There was photographs all over his room; he was an artist, he liked drawing, and he’d get inspired by taking photographs and then making them into drawings.

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: Did you take a lot of photographs?

Taylor: Later on, when I got my own camera, I’d set up little sets, scenes, and I took photographs of my friend Carol modeling some of the outfits that I’d made. I wanted to be able to look back and think, this was me then. The photographs represent a really happy time in my life, a time that was filled with love, when I first met Dennis, and the excitement of going to new places and meeting new people.

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: Amelia, when did you first become aware of Yvonne’s and Dennis’s archive?

Amelia Lonsdale: Mum and Dennis both took a lot of photographs, and until Dennis passed away in the late 1990s, they were kept separately. When a friend was clearing Dennis’s house, he came across a box labeled “In result of my death please return to Yvonne Taylor.” So, he took them back to my mum, and there were old pictures of her, love letters that they’d sent to each other. Until that point there were a lot of pictures that she hadn’t seen for fifteen to twenty years, so that was really special for her.

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: Has the archive changed since you became more involved with it?

Lonsdale: I don’t think my mum has understood herself how special the archive is until now, since I’ve started talking to her about the photographs and other people have shown an interest. So for me to be able to provide a platform for her to realize that is the most important thing for me. I would like to make a publication, but I really want to do it justice. I don’t want to rush into anything. It’s important to me that I do it right because it’s such a big responsibility. Even more so than my own photographs that I’ve actually taken.

I’ve taken pictures for as long as I can remember, and I ended up studying photography and becoming a photographer, so the archive has had an influence on me that way. In the last five years, as I’ve started really looking into the pictures, they’ve helped me understand why people take pictures, and that’s become more interesting to me than actually taking photographs.

Courtesy Amelia Lonsdale and Yvonne Taylor

Murray: How do you feel about the archive being displayed in public?

Lonsdale: It makes me really proud of my mum. It’s crazy because, while obviously there’s elements of the woman I know now in the photos, and although she’s always been the life of the party and she’s always been into fashion, it still feels when I look at them like I’m looking at someone I don’t know.