Beyond the Wall

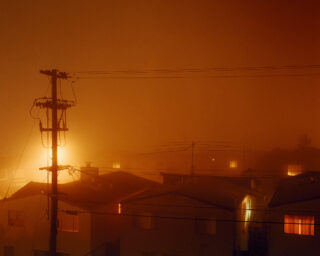

Richard Misrach, Wall, east of Nogales, Arizona, 2014

© the artist

There is a line between Richard Misrach and composer Guillermo Galindo.

On the cover of Border Cantos, it is little more than a keystroke, a simple design flourish to mark an interdisciplinary collaboration: Misrach, photographer, to the left; Galindo, composer and musician, to the right. On the pages that follow, however, that line becomes something else, a hieroglyph of a new coauthored artistic language and a symbol of all the lines that both connect and divide them. It is a line between English and Spanish, between the United States and Mexico, between white and brown, and between sight and sound, looking and listening. It is a line between an American photographer who is perfectly happy driving the nearly two thousand miles of the U.S.-Mexico border in a rented 4×4 with a tripod, a high-definition camera, an iPhone he uses for shooting, and a bottomless supply of trail mix, and a Mexican composer living in the U.S. who is perfectly happy to stay where he is, hundreds of miles away from the border, free from checkpoints, suspicion, and Border Patrol stops.

Richard Misrach, No More Deaths, 2016. Pick-up truck filled with water and food to be placed in remote regions of the Arizona desert

© the artist

The line treats them differently and they treat it differently in return.

It is also, of course, not just a line, but the line—la línea, la frontera, el límite, el bordo—the international boundary first drawn in the sand and along the shifting banks of the Rio Grande to end the Mexican-American War in 1848. Back then, the U.S.-Mexico boundary commission set out to draw a “boundary line with due precision, upon authoritative maps, and to establish upon the ground landmarks which shall show the limits of both republics.” For most of its early years, the border was just that, little more than desert dirt and river currents punctuated by marble obelisks that ran like exclamation points from the Pacific to the Gulf of Mexico to help remind everyone—the ranchers, the vaqueros, the governors, the generals, the Indians, the tourists—what side of the line they were on. There wasn’t even a fence until 1911, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Bureau of Animal Industry built one in California to keep “stray Mexican animals” that might be infested with ticks from wandering onto U.S. land. “Such a fence,” the bureau wrote thirteen years before the U.S. Border Patrol even existed, “will also assist the customs officials in preventing illegal traffic between the two countries.” The border of today, with its dedication to security against human and drug traffic, its dedication to the spectacle of national defense, was an afterthought.

Guillermo Galindo, Fuente de lágrimas (Fountain of Tears), 2014

© the artist

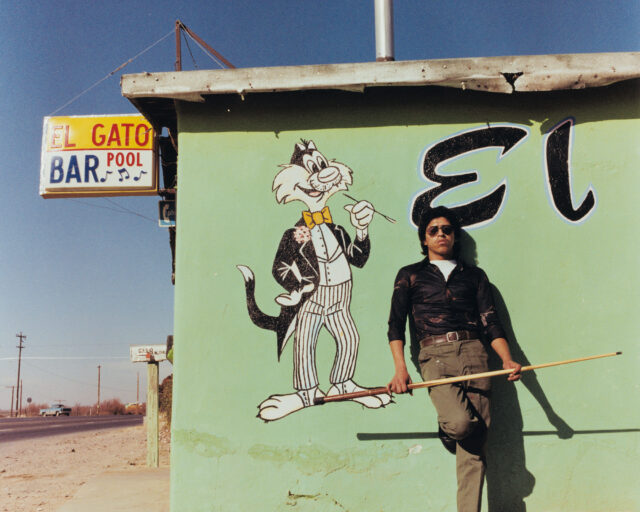

Since the 1970s, Misrach has been photographing the shifting environmental and political landscapes of the American West, the border lurking in the background of his portraits of the new desert frontier but never actually in their frame. Since the 1990s, Galindo has been making music informed by the aesthetic and cultural avant-gardes of the U.S. and Mexico, the border always audible—without it, he would still be living in the Alta California of Mexico—but never pushed too high into the mix. In 2012, their paths crossed when both of them began responding to the effects of the most recent wave of border militarization. Misrach shot the Western landscape as it was being reshaped and remapped by hundreds of miles of new steel border walls, and Galindo turned the detritus of those new walls—animal skeletons, rusting Jumex juice cans—into electro-acoustic instruments.

Richard Misrach, Border Patrol Target #3 (detail), near Gulf of Mexico, Texas, 2013

© the artist

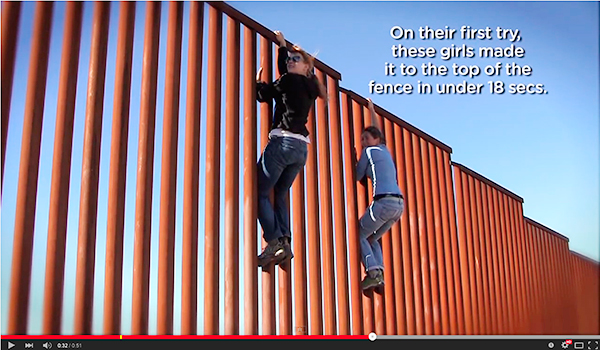

Most materially, the border of these cantos is the one that dates back to 2006, when President George W. Bush signed the Secure Fence Act and gave a green light to over seven hundred miles of new border construction and surveillance technology, a high security cocktail of imposing steel walls, checkpoint stations, radar towers, ground sensors, thermal imaging, drones, and beefed-up Border Patrol ranks. To “control the border,” between 2005 and 2015, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection paid out over $23 billion in private contracts to companies like Boeing, Raytheon, IBM, and Lockheed Martin, not to mention all of the private architectural design firms hired to make the secure border “aesthetically pleasing” (as the federal mandate put it), and all of the private prison firms—the Corrections Corporation of America, the GEO Group—who profit from upticks in enforcement and detainment. The cost of the new wall was estimated to be $4 to $12 million per mile (dependent on terrain and difficulty of construction), a hefty price tag for any addition, but especially hefty when you consider that it can be scaled by a teenager in seventeen seconds flat, without a ladder. Even a 2008 Army Corps of Engineers blueprint suggested, in fine print, just how impermanent these new walls and fences might be by their very design: “This fence construction is to be dismantled readily.”

Richard Misrach, Effigy #2, near Jacumba, California, 2009

© the artist

The vast industry of this new border extends, informally, into Mexico as well, where drug cartels and human traffickers benefit from the increased desperation and vulnerability of Mexican and Central American migrants looking for safe passage across punishing, burning deserts. This too is part of the border of these cantos, what Pope Francis has called “the humanitarian emergency” produced by overzealous border enforcement and strict detainment and deportation policies. In the past decade, some expanses of desert borderlands have become sun-bleached death zones, blistering and unforgiving sites of mass migrant death and disappearance littered with the personal effects of the missing—miles and miles of trace evidence, forensic clues to lost lives and divided families that mostly lead nowhere. They have also become a particular staging ground for unprecedented femicide, a systemic naturalization of violence against women that the border’s merger of global industry and labor exploitation has helped nurture.

The Arizona-Mexico border can now be mapped the way the Humane Borders organization does it, through RHR maps, or recovered human remains. “Each dot,” their maps read, “represents one RHR.”

The maps are full of dots.

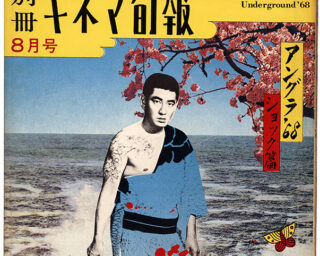

Roy Germano, still from The Other Side of Immigration, 2009

Courtesy the artist

The border wall, then, is not simply the material, built result of politically expedient legislation buttressed by defense budgets and national chauvinism. It is an ideological, social, and economic pressure point where the pulls and pushes of multiple political forces, past and present, converge in volatile and often tragic ways. To speak of the contemporary border is to speak of nineteenth-century U.S. expansionism and twentieth-century economic imperialism, decades of labor recruitment and labor deterrence, post–WWII industrialization and post–9/11 terror wars, pro-trade policies and antidrug policies, Mexican drug supply and U.S. drug consumption, the pursuit of human rights and the violation of human rights, U.S. golf courses with their ninth holes in Mexico and two-bedroom American homes with the border wall in their backyard, and the open frontier of the Old West and the carceral frontier of the New West, where campfires become klieg lights and young mothers carry their infants across live gunnery ranges because, somehow, they’re safer than the open desert.

Richard Misrach, Protest sign, Brownsville, Texas, 2014

© the artist

In her influential 1979 essay, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” art critic Rosalind Krauss noted a new school of American artists making large-scale sculpture that differed from traditional monuments because they were not commemorative or historical; they were the monument’s “negative condition.” Decades later, the border wall has truly become the monument’s “negative condition” but in moral and ethical terms, a statue of un-liberty that funnels the tired into desert bottlenecks and tracks the poor through gulches. It is a monument to the aesthetic and fiscal reaches of political theater, and a thuggish mirror of national and cultural phobias—to the limits, not the depths, of the democratic imagination.

The photographs of Misrach help us understand this. The musical instruments of Galindo help us hear it. When experienced together, however, they have the potential to do something else: to activate our own visions and our own scores for the American monuments that might still be possible to build.

Or tear down.

This essay is an excerpt from “Misrach/Galindo,” originally published by Aperture in Border Cantos (2016).