Queering “Straight” Photography

With a rush of color, David Benjamin Sherry’s new photograms gesture to abstract painting and gay history.

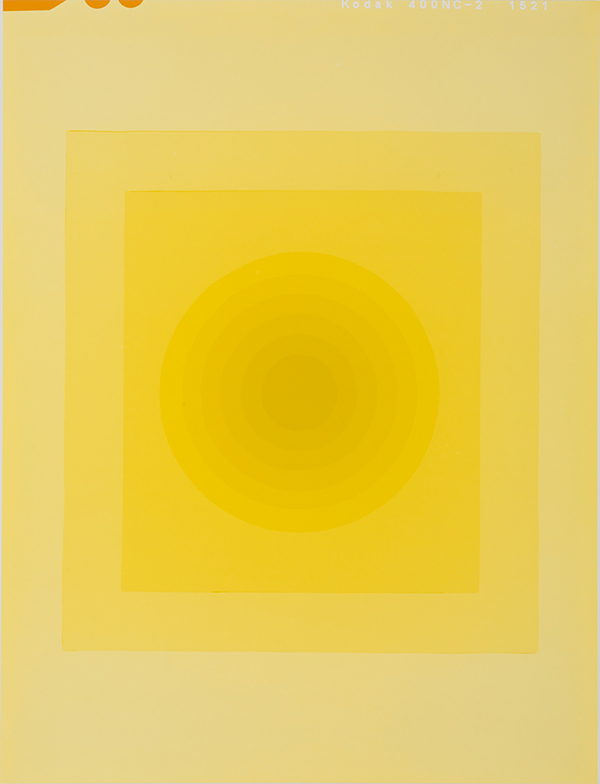

David Benjamin Sherry, Submission, 0C100M160Y, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Rare is the artist who can surprise you with a new body of work. David Benjamin Sherry, who is known largely for his color-saturated landscapes, created a new series of photograms for his latest exhibition, Pink Genesis, at Salon 94 in New York. Though bodies do appear, the photogram, by nature, is abstract—it is an index of an object and a shadow, a semi-formless copy. Sherry’s historical references are so complex, and so joyfully filled with the often-excluded formal presence of sexuality, that revisiting Pink Genesis is like rereading Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida (1980), with its seamless integration of concept, structure, and emotion. I recently discussed with Sherry the roots of this exhibition, as well as his personal, technical, political, and artistic references.

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

William J. Simmons: Darkroom photography often has the charge of preciousness levied against it, and you have never been afraid of that. What helps you remain steadfast in your commitment to analogue techniques, when some might see them as gimmicks?

David Benjamin Sherry: I have never once thought of darkroom photography as having a charge of preciousness. It’s a highly toxic, unstable, and intensely controlled process. For me, it’s also a strenuous, emotionally draining, bipolar performance that happens alone and in the complete darkness. It almost feels like I’m possessed in the darkroom. The entire act of printing in the dark has an aura of mystique and the unknown to it. I think people are now romanticizing the analog print and the unstable qualities of it, as well as the warmth that it exudes, versus the colder, less human, digital print. There seems to be a backlash happening in photography now, maybe against the digital image. I say this only because I love the analog process, and maybe my eyes are more attuned to it, but I have been noticing fewer digital images on gallery walls, and more human-oriented photographic work, which is often shot on film. It’s happening in Hollywood and in fashion photography.

The analog process—from shooting film to printing—satisfies many of my creative desires. A painter’s work comes to fruition through their materials, and my process is similar. I have experimented and taken courses in other forms of non-analog photography, but I am never fully satisfied with the process. It often feels too easy. Mostly my soul or hand feels out of the touch with the print in the end, and this is a crucial part of my work. There is sometimes an emotional disconnect with the physical print, and my work is often emotionally driven.

I love the instability of analog photography, the alchemical qualities of it, the dangers of it, the history of it, the mysticism tied to it, the exclusivity of it, the isolation of it, and the complete embodiment of it—meaning that once inside of a completely darkened room, using a small amount of light to expose a piece of paper, I actually become the internal workings of a sort of camera. While in the darkroom, I control the enlarger and the paper surface. My body becomes an integral part of the working machine. Through this process, I embody my print and become a working part of the camera. With Pink Genesis, I decided it was time to shed light upon my last seventeen years of working with film photography and to blow an analog kiss to all the other projects I’ve worked on. I decided it was time to let my hair down, to stop being protective of my darkroom process, and in fact celebrate it. And I wanted to do a show entirely of photograms, because they are in a sense the most primal form of the analog photographic process, hence “genesis” in the title.

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

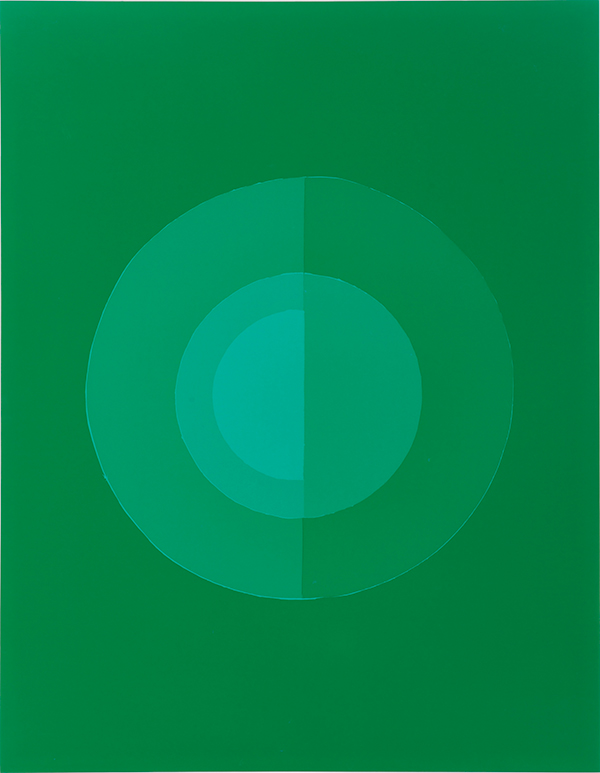

Simmons: Your work has often filled up the representational with the abstract, which I have always seen as a queer strategy. How might we understand use of abstraction in Pink Genesis? Is it comparable to Hilma af Klint’s emotional, mythological abstraction, or conversely to Josef Albers’s Bauhaus-inspired, disciplined images?

Sherry: I’m glad you see this connection, Will. I think for most people, they see my interest in abstraction as a “departure,” whereas anyone familiar with my repertoire would see that my work continually investigates the various modes of the photographic image. And, absolutely, you are spot on when you see this as a queer strategy. One of my primary goals is to locate the voids I see within the history of photography and fill them, so to speak, with a queer read on landscape, for instance, or social documentary, or the photogram. And to mingle genres and degrees of abstraction and representationality reflects that queer reality of code-switching for survival—the having to be two (or more) people depending on your context.

I hope to re-contextualize queer themes within a very “straight”-forward (pun intended) medium. (Think of the term “straight photography.”) The dominant, straight, white, male gaze and the resulting interpretation of the world was, and is, at the very heart and center of the history of photography. Once I understood this, it became a turning point for my work, which is often about being in conversation with my predecessors. I was deeply moved by Hilma af Klint’s paintings, as well as a slew of other artists whose work I’ve looked at in the past year, such as Agnes Martin, Francis Picabia, Georgia O’Keeffe, Frank Stella, Carmen Herrera, and Robert Rauschenberg—to name a few. I wish I were thinking more about Albers than I actually was, but yeah, I guess he’s always been a reference for me and he’s one of the ways through which I learned about color and how to use it.

And speaking more to my genre-hopping, for my show Paradise Fire (2015) at Moran Bondaroff in Los Angeles, I exhibited a group of pictures that represent the beginning of my first social documentary project, in which I traveled throughout the Southwest and western states following wildfires. Across many years of focusing on western landscape work, I often find myself in environmental or sociological situations that are dire, as if I can see America crumbling before my camera. The reality of our grim situation here on Earth consumes me.

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Simmons: A retreat from representation might emerge from the trauma of the rise of the Trump administration. Maybe you needed some time alone in the dark, to think and reflect. However, some queer and feminist artists, such as Nicole Eisenman, turn explicitly to representation in times of strife.

Sherry: I do find I need the balance that the more elemental, abstract work brings. It’s a way to ground myself while still tying in the ideas and themes that are important to me, and maybe to assuage some of the trauma I experience from my more literal, representational work about our current global circumstances. For instance, I began making photographs of pipelines inspired by the #NODAPL (No Dakota Access Pipeline) movement, which ultimately lead me to my first photogram in Pink Genesis titled Winter (2017). The work became not only a pipeline but also an escape tunnel, an evacuation route, and a portal to another place.

I began Pink Genesis while simultaneously photographing the protests immediately set off by the rise of the Trump administration. I documented with an 8-by-10-inch camera some of the major protests here in LA. I felt emotionally and psychically spent. Like you said, the darkroom offered a sense of internal solitude and helped me find my center again. So, yes, I turn to representation in these times of strife, and sometimes away from it! I also like to think of my work as a signifier of something to come. Paradise Fire was ominous. Maybe Pink Genesis is my attempt to cast a future spell upon the viewers and create a harmonious, peaceful, uplifting, self-loving balance spawned by one of the darkest years of my own and many others’ entire lives thus far. In all honesty, I believe this work saved me from completely falling to pieces in the last year.

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Simmons: There’s a delicacy or precariousness in the way the pieces in Pink Genesis are framed—the mounting of the photograms highlights the material presence of the image by creating distance between the paper and the backing. What was your thought process here?

Sherry: I wanted the photograms to embody the same feeling of floating that went into the work. Being in the dark while making this work really plays with one’s sense of gravity, like being in space or underwater. I worked to maintain a certain sense of disorientation and a feeling of flotation in the individual pieces. I felt it was only necessary to also “float” the works within their frames. I chose not to put glass or Plexi in front of the pieces, just for the duration of the exhibit, so the viewer can enjoy all the physical beauty in the actual print.

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

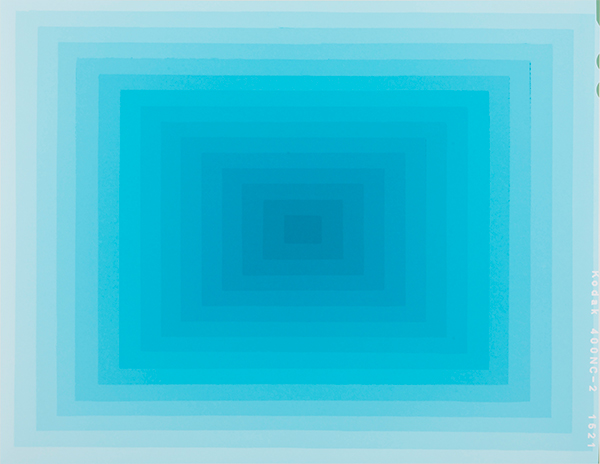

For this work, I used an unusual hybrid photographic paper, which can be used in analog or digital process. Most photograms are made with glossy paper. Sometimes this can have beautiful results, but I wanted to make minimal photograms that specifically had depth, like my favorite minimal paintings. On matte paper, these works often feel like watercolors, and this was intentional. I tried to make paintings prior to making this body of work, but it somehow looped back around into my photographs.

Simmons: Leaving the edges of the negative in the photogram, complete with the word “Kodak,” could be read as either ironic branding or a sincere homage. What prompted this decision?

Sherry: I intentionally left the film edge on a handful of the works on view to expose my process and counter the misconceptions about my work being digital. I thought it may be time to give my process more glory, while also flexing my “pink analog muscles” with the intention of bringing something new and queer to the genre of photograms.

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Simmons: How might we characterize a queer iconography in this exhibition? There are some very clear references, such as Sublime Bottom I, 0C180M0Y, and Sublime Bottom II, 150C40M0Y. But there are also some more subtle references, such as your homage to—or co-opting of—both Yves Klein’s masculinist spectacle Anthropometries, and Robert Rauschenberg’s Autobiography (1968). I’m also reminded of Chicago Imagist Roger Brown’s Peach Light (1983), a surreal illustration of the soft pink and orange light used in gay bars in the ’80s to mask the skin afflictions caused by HIV/AIDS.

Sherry: There is so much queer iconography in this show! The title itself is a play on James Bidgood’s 1971 masterpiece Pink Narcissus, a film that helped shape the way I view the world. I also was thinking about Robert Rauschenberg’s collaboration with Susan Weil in Untitled (Double Rauschenberg) and Female Figure (both ca. 1950), which used exposed blueprint paper. (I wasn’t thinking of Roger Brown’s Peach Light, but what an amazing piece of art, and I love that you are reminded of it!)

I was also thinking of a Robert Gober piece I remember seeing at his 2015 MoMA retrospective The Heart Is Not a Metaphor. That entire show was profound, but this one piece, in which he combined his face with his dogs in a self-portrait mask, really resonated with me, maybe because pets for queer people really become our family, our children, which I find poignant. So, I attempted to merge my own body in one piece from Pink Genesis, with Wizard, my dog, titled Metamorphosis (Self portrait with Wizard), 150C40M0Y (2017).

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

My work always feels slightly indebted to AIDS-related artwork. Once, in grad school, my professor at the time, Collier Schorr, said I made my art as if I was a survivor of the AIDS crisis. At the time, I didn’t really understand what she meant. And while I can’t pretend to understand what it was like, I do feel part of the legacy of a generation of gay men, artists, and activists who were felled by the disease. I also met many of my mothers’ friends at a young age, who all had lasting impressions on me—the first gay men I ever met—and many eventually died from AIDS. This had a profound effect on me. I feared that being gay meant I would automatically have AIDS, and at age eight, I wasn’t ready to die. So, to Collier’s point, I do mourn the loss of so many great artists, and I make work from this place of queer iconography. I was always shocked by how the recent history of photography and the history of art tried to tackle AIDS-related work—or didn’t, as was too often the case. Our art history books need to be re-written.

David Benjamin Sherry: Pink Genesis is on view at Salon 94, New York, through August 4, 2017.