A Different Kind of Protest

How did Michael Schmidt’s independent workshop change postwar German photography?

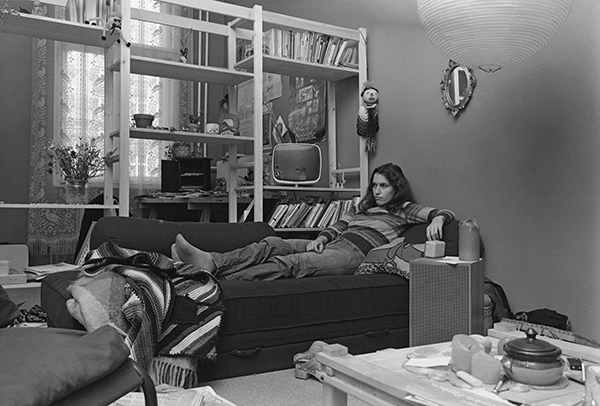

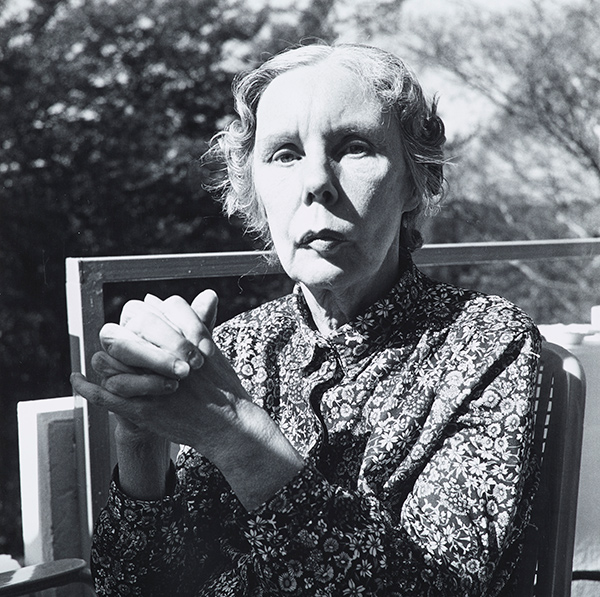

Uschi Blume, Untitled, from the series Worauf wartest Du (What are you waiting for), 1980

In 1976, the same year that Bernd Becher inaugurated his now-famous photography class at the University of the Arts in Düsseldorf, Germany, the photographer Michael Schmidt founded the Werkstatt für Photographie. Sprung from a need for creative dialogue about the medium, for the following ten years the Werkstatt offered an elaborate program of classes, and invited German and international photographers, including Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Larry Clark, William Eggleston, Robert Frank, John Gossage, and Stephen Shore, to hold workshops and exhibit their work. Often, this was their introduction to a German audience. In what was then West Berlin, it was by no means inevitable that an independent workshop would be at the heart of change in German postwar photography. Now, with the expansive catalog Werkstatt für Photographie. 1976–1986 (2016), produced for the occasion of three exhibitions organized by the curators Florian Ebner, Felix Hoffmann, Inka Schube, and Thomas Weski, a hidden chapter of the country’s photographic history has been rediscovered.

© Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

© Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

The Werkstatt was not a school in the traditional sense. Despite its quick development as Germany’s leading institution to develop, teach, and advocate for a new understanding of documentary photography, it did not provide a degree. Independent, yet part of the Volkshochschule Kreuzberg (Adult Education Center Kreuzberg)—one of the country’s public adult-education centers, many of which still exist today—the workshop’s operating principle was accessibility based on passion. The school was open to anyone, as Schmidt stated in a 1979 interview with Camera magazine, who was interested in studying “photography as a serious means of personal expression.” With darkrooms, various cameras, an office, and two spaces that served simultaneously as classrooms and exhibition venues, the idea was to provide an alternative to standard institutions—to allow for a less technical, more creative, approach to teaching, focused on innovations in content and style, as well as lively discussions about the medium.

© Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

As Ute Eskildsen, one of Germany’s first photography curators, describes in the 1995 exhibition catalogue Michael Schmidt: Fotografien Seit 1965 (Michael Schmidt: Photographs since 1965), Schmidt, who was born in Berlin in 1945 and who hadn’t trained as a photographer, encountered the medium by chance while working as a policeman. Intrigued by a colleague’s camera, he began to make pictures in 1965. At first, eager to acquire the skills needed to master the camera as a technical tool, he joined the Verband Deutscher Amateurfotografen (Association of German Amateur Photographers). In 1969, Schmidt’s growing need for a more creative dialogue, and the development of his own practice of subjective response to Berlin and its inhabitants, had exceeded the association’s educational capacity. Instead of looking for other classes that could provide such an exchange, which, in any case, didn’t exist, he began to teach at the adult education centers in the Berlin districts of Kreuzberg and Neukölln.

© and courtesy the artist

By the mid-1970s, like Schmidt’s career, West Germany’s photographic infrastructure was heading in a different direction. Schmidt had successfully published his first book, Berlin Kreuzberg (1973), had held several exhibitions in Berlin, and was teaching and working full time as a photographer. Meanwhile, a few commercial and nonprofit galleries had been established in Aachen, Berlin, Cologne, Essen, Hamburg, Hannover, and Kassel. Museums had begun to recognize photography as a medium worthy of display, and art schools offered photography classes, although often not with a degree in creative photography. The increasing exposure of the visual language of photojournalism, promoted through a variety of magazines, also informed and influenced a number of individual photographic practices, including Schmidt’s.

© the artist

According to Eskildsen, however, it was Camera magazine—through which Schmidt was introduced not only to historic photography, but also to contemporary, international approaches, particularly in American photography—that would have a more significant impact on him. In 1976, after Schmidt had already been developing the Werkstatt’s concept and program, he became a member of the Gesellschaft Deutscher Lichtbildner (Society of German Photographers), where he met André Gelpke, Heinrich Riebesehl, and Wilhelm Schürmann—all photojournalists, yet each pursuing a distinct personal practice. (All would be future guests of the workshop.) In sharing their desire for a photography that was not compromised by commercial pressure, Schmidt must have felt confirmation that is was time for an alternative network to emerge.

© and courtesy the artist

As Thomas Weski and Enno Kaufhold have described, to attend the Werkstatt’s program, participants who did not already have a background in photography first had to sign up for a series of introductory classes. After acquiring the necessary technical skills and presenting their portfolios to the faculty—initially consisting of Schmidt and his former student Ulrich Görlich, and joined by Wilmar Koenig and Klaus-Peter Voutta in 1977—students could attend core and advanced courses. Classroom debates around content, aesthetics, and intention were grounded in Schmidt’s belief in a “sincere” photography, which required photographers to probe their personal relationships with their subjects. Given that these images were, therefore, intimately connected to the person who made them, the critiques could be quite tough. This new generation of photographers made images of landscapes and cityscapes, neighborhood studies, interiors, and portraits. Hildegard Ochse’s photographs of Berlin courtyards and street views, for example, focus on the tamed or uncontrollable appearances of nature, whereas Wolfgang Eilmes’s Kreuzberg (1979) is a sociological study of that neighborhood and its people.

© the artist

While the Werkstatt and its faculty did not impose a specific type of imagery or genre, Weski, and former students, have stated that the photographic method taught throughout its first years was closely connected to Schmidt’s creative practice: a sober, factual, almost analytical style of documentary photography, as exemplified in Schmidt’s 1978 book Berlin-Wedding. Divided into two sections, “urban landscape” and “people,” Schmidt depicts Berlin’s Wedding district as a complex fabric of postwar architecture, pavement, and wasteland particular to construction sites. While these fabricated spaces are deprived of any human presence, the neighborhood’s inhabitants are portrayed at work and at home, juxtaposing the manifestation of their personalities in social and private spaces.

© the artist

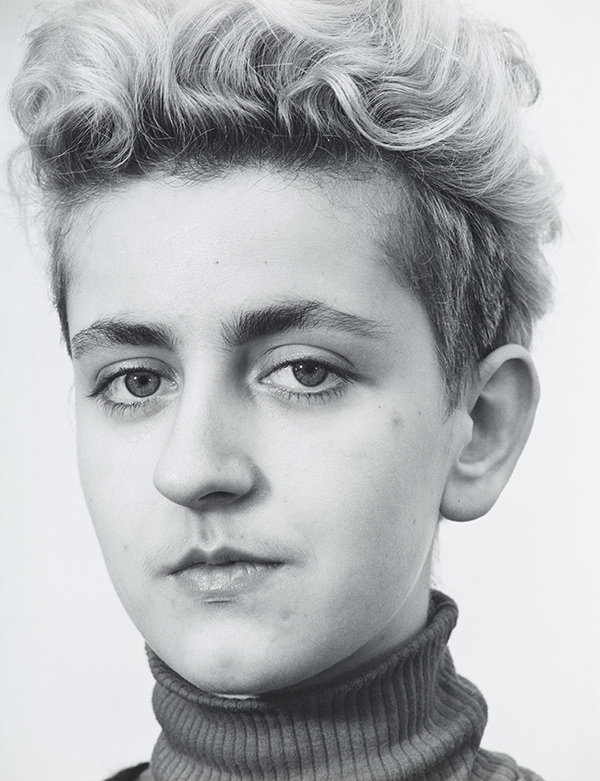

To focus on his own work, Schmidt stopped managing the Werkstatt in 1977 and was replaced by Ulrich Görlich, yet he continued to teach and to assist in developing the workshop’s profile. The following years were marked by the Werkstatt’s increasing interest in American photography and establishing a dialogue between Berlin and the United States, mainly organized by Wilmar Koenig. Individual and group exhibitions were presented by Ralph Gibson, Larry Clark, Lewis Baltz, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, and Stephen Shore, who introduced his pioneering approach to color photography; the collective influence of these photographers, in addition to Schmidt’s increasingly looser involvement, the influx of new photographers, and changes in the Werkstatt’s leadership—Wilmar Koenig and Klaus-Peter Voutta replaced Görlich in 1982—allowed for a more subjective photographic language to emerge, as revealed in the portraiture of Christa Mayer and Uschi Blume.

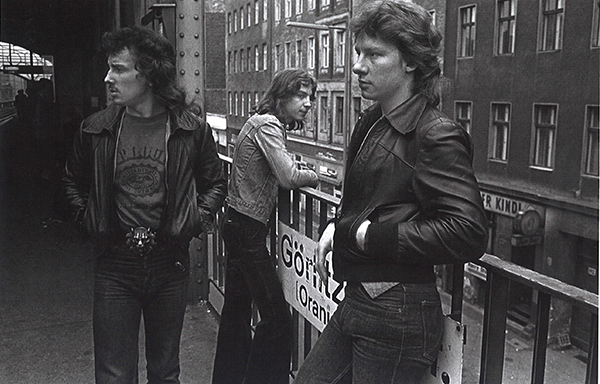

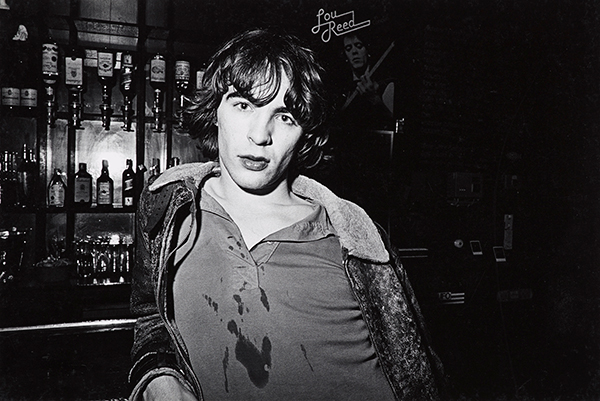

Instead of observing from a distance, Mayer and Blume engaged with their subjects in close proximity, at times even including the photographer’s shadow. In fact, they are part of their environment: Blume of the punk scene she depicts at a Berlin nightclub, and Mayer of the psychiatric ward where she worked as a therapist. As much as Blume’s Worauf wartest du (What are you waiting for) (1980) and Mayer’s Abwesende. Portraits von einer psychiatrischen Langzeitstation (Absentees. Portraits from a long-term psychiatric unit) (1982–86) resonate, respectively, with the grunginess of Larry Clark and the oddity of Diane Arbus, the series are also innately German. Blume and Mayer, together with this new generation of German photographers, reacted to the country’s sociopolitical past and its ramifications in the present, and posed questions about the relationship between society and the individual, as well as the complex notions of place and belonging.

© Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive

From 1984, when the Werkstatt underwent its last change of leadership, until its eventual dissolution two years later, an increasing number of photographers continued to push the subjective possibilities of the medium, culminating in the 1986 exhibition Remains of Authenticity at the Museum Folkwang in Essen, which was organized by one Ute Eskildsen. Many of the exhibition’s participating artists and photographers were connected with the Werkstatt or were former students of Schmidt. In her essay “Remains of Authenticity. Notes on photographic perspectives in 1980s Germany,” Carolin Förtster remarks that in different ways, most of them, including Schmidt, questioned not only the narrative, but also the representational capacities of the medium. Yet, it was not a disenchantment or crisis in photography that brought the Werkstatt to an end, but a change of management of the Volkshochschule Kreuzberg, ultimately leading to budget cuts and restrictions regarding the workshop’s autonomy. With the collective resignation of its members, the Werkstatt closed in the summer of 1986.

There’s more to rediscovering the Werkstatt für Photographie than only amending the history of German photography, or giving artists the credit and exposure they have earned, such as recognizing the striking imbalance between male and female teachers. The Werkstatt was first and foremost driven by the idea to make a difference, to create an environment that other institutions did not or could not provide. In doing so, it became a place of autonomy and a proof that art, indeed, can change our consciousness of what is possible.