On the Edge of the American Dream

John Divola, Untitled (woman watering, striped top), 1971–73

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica

When most people hear “Golden State,” they think of sunshine and Stephen Curry, but curator Drew Sawyer was thinking about the 1940s internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. He was also thinking about how photographers, since the 1970s, have challenged romanticized images of California. Currently on view at Marianne Boesky Gallery, his group exhibition Golden State includes photographs by Anthony Hernandez, Catherine Opie, Larry Sultan, and other California-based artists. At a moment when California is being heralded as a leader of “the resistance,” these photographers focus on various marginalized communities, demonstrating how not all Californians have access to a utopic, liberal vision of the Golden State. People there are still struggling to be recognized as citizens, to feel like they belong, and to survive.

Christina Fernandez, Lavanderia #11, 2003

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica

Will Matsuda: Why an exhibition about California? Why now?

Drew Sawyer: When the gallery asked me to organize a show, it was the day after the presidential election. I knew I wanted to do something that was timely but that wouldn’t feel dated by the time it opened in April. Already within the first week after the election, California was emerging as a state of resistance. There was talk of “Calexit.” In recent years, the state seemed to have become this liberal bastion. But many conservative movements have originated in California, and one would only have to go back ten years to when the state attempted to ban same-sex marriage.

Catherine Opie, Flipper, Tanya, Chloe, & Harriet, San Francisco, California, 1995

Courtesy the artist; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

California, in some ways, represents the country as a whole, and also the country’s ideals. Many of our ideas of California, influenced by Hollywood shows like HBO’s Big Little Lies, have to do with an idealized vision of the American Dream. So I was particularly interested in the contradictions of the state. California has one of the largest economies in the world, and it has one of the greatest number of billionaires. At the same time, it has the highest rate of poverty in the country. It felt necessary to think about these polarities, since the country is so polarized right now.

From an art historical standpoint, the state also seems relevant because many of the California photographers I ended up selecting have had major survey shows in the last few years: Anthony Hernandez at SFMoMA in 2016 and Larry Sultan at LACMA in 2014 (and now currently at SFMOMA). But neither of those shows have travelled to the East Coast. Neither of those artists even have commercial galleries that represent them on the East Coast. It seems like the perfect time to bring this work to New York.

Anthony Hernandez, Rodeo Drive #19, 1984

© the artist and courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Matsuda: The title, Golden State, evokes the usual California connotations: sun, surfers, and LA. But the exhibition seems to attack these romanticized visions straight on with images portraying the hardships endured by Latino day laborers, Japanese Americans facing internment, and other marginalized identities. What were you looking for when you were selecting photos?

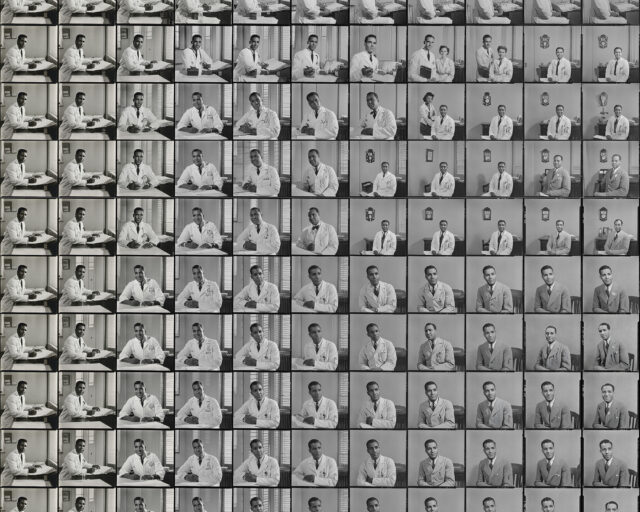

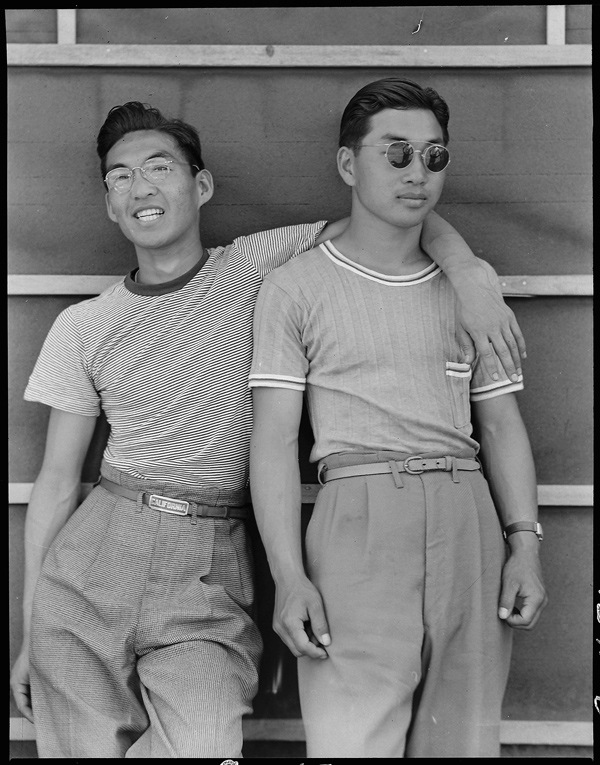

Sawyer: I wanted to complicate that idea of California, the one that gets represented so often. You mentioned the Dorothea Lange photographs of the internment of Japanese Americans, and those really were the inspiration for the exhibition. This spring is the seventy-fifth anniversary of the internment. In 1942, the federal government commissioned Lange to document the process of interning over 100,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans. Even before she started photographing the roundups and the camps, Lange photographed Japanese Americans in their homes and at their workplaces. The mandatory internment announcement had already been made, so the people in these photos knew what was coming and knew what they would be forced to leave behind: their homes, their businesses, their jobs, their college educations. Those are the photographs I ended up choosing. In some ways, I think they are the most subversive because Lange really showed the degree to which these individuals were truly American and so fully integrated into the economy and American society.

Dorothea Lange, College students of Japanese ancestry who have been evacuated from Sacramento to the Assembly Center, Sacramento, California, 1942

Courtesy National Archives

Matsuda: I know this history because I am Japanese American and I know Lange’s work. But for people walking into the gallery, the context of internment is not entirely clear. A suburban family poses on a manicured lawn, or two hip guys strike a pose for the camera. There are no captions to explain that these were taken right before their entire communities were uprooted and imprisoned. Don’t you think these kinds of photographs need context?

Sawyer: I did think about that, but of course commercial galleries don’t usually have wall labels, so the full captions are on the checklist and in the accompanying catalog. In the end, I also wanted the show to be beautiful, to be visually enticing, and I think those contradictions are even more interesting. I could’ve shown work that was more explicitly about internment, but I selected a series of portraits that felt more cohesive with the rest of the exhibition.

Matsuda: Right, your focus is on people. But, another common vision of California is the grandeur of the landscape—places like Big Sur and Yosemite.

Sawyer: The landscape, particularly the suburban landscape, does appear. When you think of California photography, you may think of Ansel Adams or nineteenth-century photographic surveys of the landscape. But for me, that is a separate tradition. Since Lange was my starting point, I really wanted to look at images that examine California’s economic systems, and that might be more rooted in cultivated landscapes than in natural ones.

Buck Ellison, Pasta Night, 2016

Courtesy the artist and Park View, Los Angeles

Matsuda: John Divola, Buck Ellison, and even Larry Sultan’s images feel quite suburban. What is it about this setting that makes it a productive backdrop for the exhibition?

Sawyer: I think the idea of suburbia and California are linked with the American Dream. Even looking through the current issue of Aperture, “American Destiny,” a lot of the photographers or photographs are actually from California. But each of those photographers gives a very different picture of suburbia. In John Divola’s work from his San Fernando Valley series, from the early 1970s, there seems to be a certain sense of postwar conformity in the pursuit a middle-class life. I chose several images of people watering their lawn. They are comical but also a bit sad.

Buck Ellison, the youngest photographer in the show by far, has a very different portrayal of suburbia. He’s concerned with depicting a very specific elite, white culture—not the middle class. And to me, his work provides a really interesting dialogue with Dorothea Lange’s photographs. While Lange’s photographs show the failure of liberalism in the face of war, Buck’s photographs seem to capture how certain progressive or liberal ideals have not only succeeded to some extent but also become commodified into identities, brands, and luxuries. In Buck’s staged photograph of the gay couple making pasta, it’s sort of like, “Oh, they’ve won their equality, and now all they want to do is make homemade pasta with their expensive culinary equipment in their beautiful suburban kitchen.”

Larry Sultan, Canal District, San Rafael, 2006

Courtesy the Estate of Larry Sultan, Casemore Kirkeby Gallery, San Francisco, and Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

A lot of Sultan’s work also has to do with home and suburbia too, especially the San Fernando Valley where he grew up. I chose work from Homeland (2006–9) partially because it was his last show and he hasn’t had a show in New York since he passed away in 2009. He shot the work in Marin County, a wealthy and liberal enclave just north of San Francisco where Buck Ellison happens to be from. I thought the series also provided another conversation with Lange’s photographs, since he hired immigrant day laborers to act out scenes in these sort of interstitial suburban spaces, like fields and creeks between housing developments. He made the series both before and after the subprime mortgage crisis, so the landscapes probably took on new meanings for him. And these images of immigrants walking in fields probably take on new meanings for us today. I hope the show provides a variety of perspectives on suburban lifestyles.

Matsuda: And who has access to it.

Sawyer: Exactly.

Will Matsuda is the Social Media Associate at Aperture. Drew Sawyer is the William J. and Sarah Ross Soter Associate Curator of Photography at the Columbus Museum of Art and the Arts Editor at Document Journal.

Golden State is on view at Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, through April 27, 2017.