An Exhibition Where Every Opinion Matters

At the Art Gallery of Ontario’s annual photography prize, four artists compete for your vote.

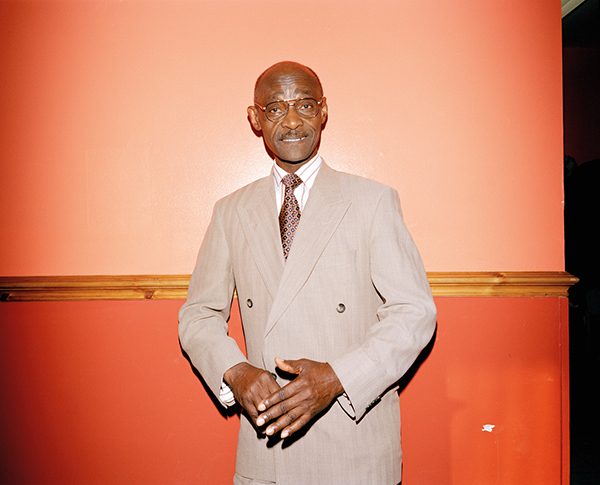

Liz Johnson Artur, Untitled, 1986–2010, from the Black Balloon Archive

Courtesy the artist

The AIMIA/AGO Photography Prize makes a critic out of all who enter. Throughout the Art Gallery of Ontario’s annual exhibition, touchscreen monitors encourage visitors to vote for the “artist whose works speaks to you.” Handed the role of juror, viewers interact with the exhibition with a critic’s eye, forming their own responses and judgments, and assessing the work through aesthetic, concept, or both. The four finalists this year—Raymond Boisjoly, Taisuke Koyama, Liz Johnson Artur, and Hank Willis Thomas, who share an interdisciplinary approach—have already been vetted in two rounds in a nomination process led by the AGO’s photography curator Sophie Hackett.

By asking the audience to vote, the prize pits each artist against one another, resulting in four separate mini-shows rather than one unified exhibition. The transition between each artist’s area, or between each separate show, is signified by a small video screen with headphones where an “expert”—the director of a science museum, a talk show host, a curator—campaigns for why you should vote for a certain artist. These acts of rhetorical persuasion, along with the voting screens and wall text, however, are the only hints that this is not a typical museum exhibition.

Raymond Boisjoly, From age to age, as its shape slowly unraveled, 2015. Installation at the Art Gallery of Ontario, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Catriona Jeffries Gallery, Vancouver

The first mini-show is Raymond Boisjoly’s installation of large-scale photographs, From age to age, as its shape slowly unravelled (2015). Printed on vinyl and placed directly on the wall, the images become part of the cavernous room. The photographs, which range from life-size to larger-than-life, often require a tilt of the head to view in their entirety. To create this series, Boisjoly scanned Statues Also Die (1953)—an anticolonial French film by Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Ghislain Cloquet—while it played on his iPhone and iPad. As Boisjoly explains in a statement, “the distortions in the images result from the scanner’s inability to fix the film’s movement.” By replicating the repulsion of movement inherent in daguerreotypes, Boisjoly’s hypercontemporary images recreate technical pitfalls that existed more than a century ago.

Raymond Boisjoly, Station to Station (detail), 2014

Courtesy the artist and Catriona Jeffries Gallery, Vancouver

The results of these distortions are seen in various ways. From afar, the dust particles on Boisjoly’s photographs resemble constellations, bringing attention to the physical origins of the work. In The Objects Themselves (And Now Their Image) (2015), a triptych of statues’ heads appear like mannequins detached from the rest of their bodies. The video’s rapid movement has altered one head so that it looks in both direction at the same time, a contemporary Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and endings. In another, Subsequent Categorizations (Institutional Framings) (2015), the scan has splintered the statues from the video, crushing them into the right side of the photograph; they appear as if they’re invading the image, an apt metaphor for the colonialism that Boisjoly grapples with. The only deviation from grayscale is a tricolor shading, the same effect of viewing a 3-D images without the requisite glasses.

Liz Johnson Artur, Untitled, 1986–2010, from the Black Balloon Archive

Courtesy the artist

A few steps away, Liz Johnston Artur’s Black Balloon Archive (1991–ongoing) emphasizes the importance of the everyday. Instead of being mounted and framed, the photographs are displayed in vitrines, or adhered to the wall by magnets—an ode to hanging photographs on the refrigerator. And Artur’s photographs are exactly the kind you would hang on the fridge. Full of joy, Black Balloon Archive documents a broad range of Black experiences. “Whether congregating at parties or clubs, on streets, in parks or at churches, the groups in Artur’s photographs emphasize family, friendship, style, and joy without generalization,” the exhibition text explains. Artur captures her subjects in settings of celebration, where they’re looking, and maybe feeling, their best. The vitrines showing Artur’s collection of archival documents, both her own photographs as well as ephemera she has gathered, double as light boxes. The scrapbook-like documents become photographs; light shines through the newspaper image, becoming an accidental negative.

Taisuke Koyama, Rainbow Variations, 2009–ongoing. Installation at the Art Gallery of Ontario

Courtesy the artist and G/P Gallery, Tokyo

In the same room, scrolls of colorful photographs by Taisuke Koyoma are draped over black frames. To view the images themselves, visitors must weave in and out of a maze of these photo–sculptures. Unfortunately, the display is the most interesting component of the work. The aesthetically pleasing gradations—fading in and out of blue, pink, yellow, and green in vertical lines—disclose slight imperfections when inspected closely: watermarks, hair, and dust particles. Yet, Koyoma’s proposed line of inquiry, investigating the “relationship between organic processes, natural phenomena and imaging technologies,” remains ambiguous.

Hank Willis Thomas, Raise Up, 2014

Courtesy the artist and the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

The clear winner is Hank Willis Thomas. His work takes up the most physical space in the show, spanning two separate rooms and a hallway. In the first room is Thomas’s sculpture Raise Up (2014), from the series Punctum (2014–ongoing). Bronze heads and arms peak over a long white pedestal. Cut off at eye level, or sometimes right below, at first it might appear as if the Black men portrayed are drowning. And then you realize: maybe their arms are raised in surrender to police. Looping back, the reference for this work appears: a photograph by Ernest Cole from the early 1960s of gold mine recruits stripped down for medical evaluation. By referencing an archival photograph and using bronze, Willis creates a memorial.

One room over are seven of Thomas’s photographs, screen-printed onto retro-reflective vinyl, and activated with the flash of a camera or LED flashlight. Once hit with light, the photograph flares into focus, goes dark, and then lights back up for a final time. An artist statement reads, “When we activate the works with light, they become vivid evidence of historic moments easily forgotten in our fast-paced visual culture.” Do you look at the photograph as an image on your phone, or in the ambient light of the gallery? In mandating that these pieces be illuminated with a flash, Thomas puts the viewer in the role of the photographer, sharing some of the agency of not only viewing, but also of making the photographs, and bringing often-forgotten historical moments back into focus.

Hank Willis Thomas, Turbulence II (left), The Law of the Land is Our Demand (right), 2017

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

By allowing the audience the agency to choose which photographer they think should win, the AIMIA/AGO Photography Prize encourages visitors to actively interact with the works, as opposed to passively viewing them. Each artist mirrors this with work that also invites participation, enhancing the interactive experience. Yet whether a visitor views the art aesthetically or conceptually, Thomas is ahead on both fronts. (The official winner will be announced on December 4.) Thomas’s work requires viewers to engage with his photographs, participating in the development of the images in a novel way. The work itself is striking, and the fact that you can “develop” photographs—by taking pictures of them—means you get to revisit the images over and over again on your own camera-roll. While this exhibition’s framework turns you into a critic, Thomas turns you into a photographer.

The AIMIA/AGO Photography Prize is on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario through January 14, 2018.