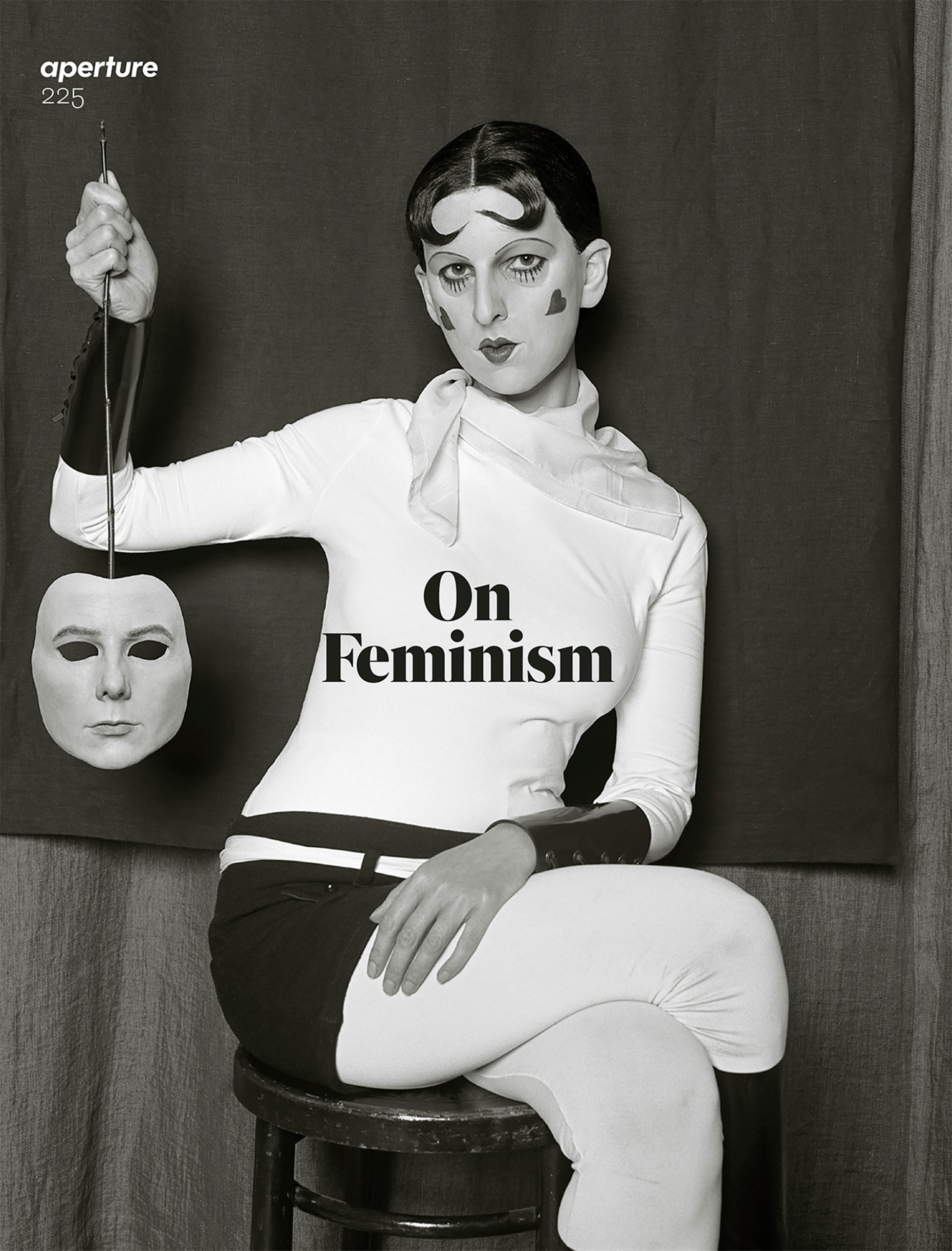

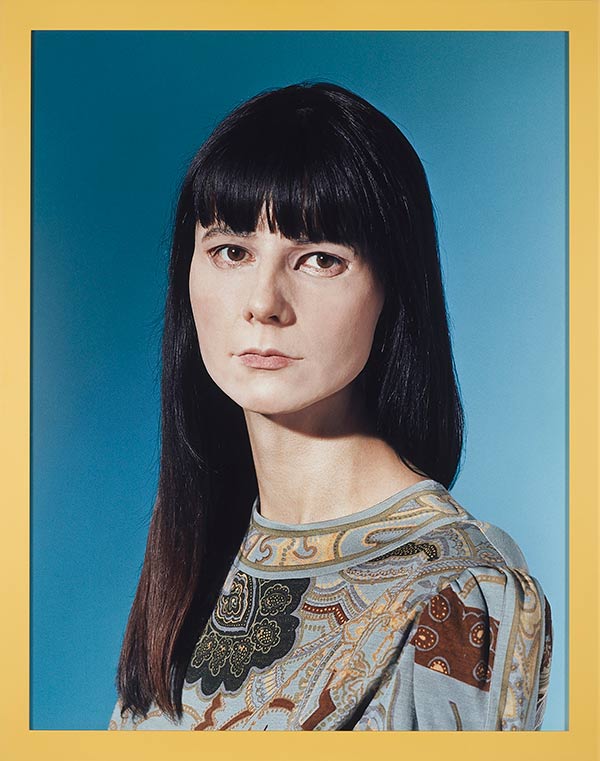

Gillian Wearing, Me as Cahun Holding a Mask of My Face, 2012

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London

On the cover of Aperture’s “On Feminism” issue is a photograph by Gillian Wearing, who recreated a 1927 self-portrait by the French writer and artist Claude Cahun. Rediscovered in the 1990s, Cahun was known for her gender bending, theatrical photography. “Wearing, like Cahun, conceives of gender as multivalent,” Jennifer Blessing writes in an introduction to a portfolio of Wearing’s previously unpublished early work. Ahead of her latest exhibition, Wearing spoke about Cahun, feminism, and her “spiritual family” of artists with Nicholas Cullinan, director of the National Portrait Gallery in London, where Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the mask, another mask opens in March 2017.

Nicholas Cullinan: I wanted to begin by asking you about Me as Cahun Holding a Mask of My Face, from 2012. When did you first discover Claude Cahun’s work, and what has it meant to you over the years?

Gillian Wearing: I read about Cahun in the mid-’90s; I think it was in an article in the Guardian. Her work was being written about as if it were a new discovery, although it was more of a rediscovery, as her photographs had been bought at an auction in the 1970s after her partner, Marcel Moore, passed away. The photographs seemed very playful, and also very apt for that moment, something that has not gone away over time. In fact, we are now finding new ways to look at her work.

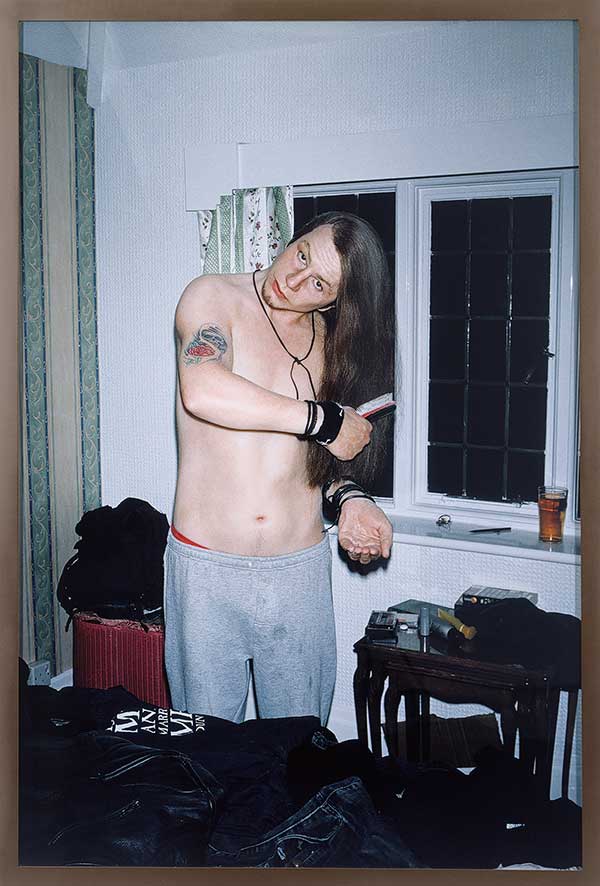

In the ’90s I thought about her work as performed versions of the self—something that now feels innate and even commonplace to anyone with an Instagram account. I can track my own sensibility to this from my teenage years onward; I felt compelled to take photographs of myself posing in order to crystallize a perfect image of myself, and mainly for my consumption only. It was not always about vanity and creating an illusion, but also trying to get close to how I might look or be at a certain point in my life. A lot of this is captured in my series My Polaroid Years, which look very much like selfies but were all taken with a Polaroid camera between 1988 and 2005. So when I became aware and interested in Cahun’s work, I felt there was some kind of affinity, a need that she had to take images of herself that I related to.

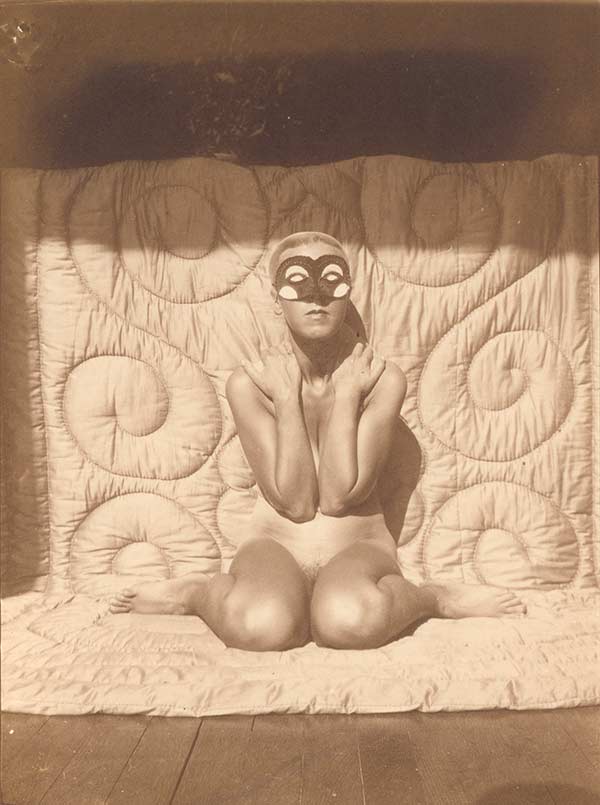

It’s only fairly recently I found out that she did not exhibit her photographs, and that she saw herself primarily as a writer. We don’t entirely know why she took the images, although some fragments of her photographs did appear in her collages. With very little to guide us, a lot of what we can say and think about Cahun and her photographs is only conjecture.

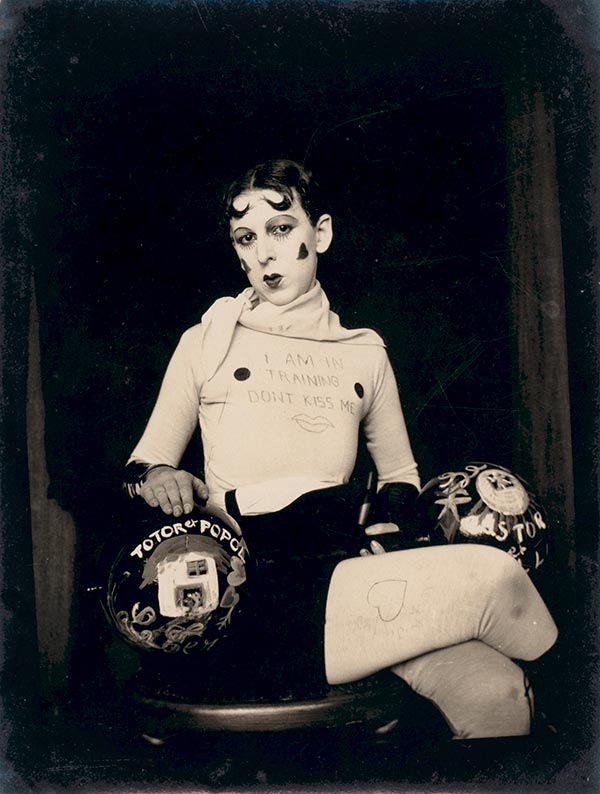

© Jersey Heritage and courtesy Jersey Heritage Collections

Cullinan: Leading on from that, why did you choose this particular image of Cahun’s to re-create? Could you talk a bit about the process behind making this work?

Wearing: I chose it because it was quite an emblematic photograph. I liked the way her face, which was painted, already resembles a mask, and that led me to thinking about introducing a mask of my own face into the work. So both of us are represented as masks in the image.

The whole process in creating the photograph takes about four months. A mask is made of Cahun’s face that will fit my face. So the sculpting of her face is done over a cast of mine. In the shoot I wanted to create a pose similar to her original one, with the head tilted down, the legs crossed. I didn’t want to have the text of “I am in training don’t kiss me,” as this image is about our relationship and shared interests in the masquerade. I shoot with film rather than digitally, and it was a ten-hour shoot. I think film makes me much more thorough. I know I can’t see the images before they are processed, so I try and have as many choices of shots and lens changes as possible.

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Cullinan: It’s fascinating that you take on the roles of artists, as well as your mother, father, sister, and brother, and yourself at different ages. So, is Cahun part of your “family,” so to speak?

Wearing: In my series Me as … (2008–13), apart from Cahun, Warhol, Arbus, and Mapplethorpe, there is Weegee, Sander, and Fox Talbot. I classify them all as my spiritual family.

Cullinan: How have Cahun’s example and the way she addresses issues of gender politics, identity, masquerade, performance, and self-portraiture through her work resonated with you?

Wearing: Like a lot of people, apart from my scant knowledge of her in the ’90s, I didn’t really have much exposure to Cahun until the last fifteen years, when quite a few books have been published on her life and work. And it is within this time that I realized she was an activist, as well as an artist, writer, etc; that she was prescient in her ideas of renegotiating what gender means, and that it can be neutral. So there is a really interesting convergence of her life and art.

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Cullinan: Is the fact that both of you work primarily using photography as your medium significant, or is photography simply a vehicle to explore both portraiture and self-portraiture?

Wearing: I have always classified my work as portraiture, from my filmic works to photography and sculpture. You could say the terminology is the vehicle. The word portrait is a very open term; it allows for experimentation, discovery, and the fact that almost anything can be a portrait, whether it is of a human face or a bouquet of flowers.

© the artist and courtesy Maureen Paley, London

Cullinan: I want to ask you about the exhibition we are working on here at the National Portrait Gallery, which will open next March: Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the mask, another mask. Of course, in doing this, we are generating an intergenerational dialogue between two woman artists. As such, does you consider yourself a feminist? Do you identify in particular with one or more periods/waves of feminist art?

Wearing: Yes, I am a feminist. I believe in equality, and I believe anyone who thinks the same is a feminist. I am indebted to many women over the years who have achieved change for other women through feminist art, politics, and writing. I don’t identify with any one period, as I identify with different things over different moments in time.

I remember what I consider the first feminist artwork I became aware of: Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1973–79). It seemed very radical, both as an idea of what art was and that something that would have normally been private was being put on display. I think women artists have really pushed that envelope in terms of the personal being art. In my own work over the years, people have said to me, “You can’t show that, it’s too revealing.” This has happened with the confessional works and even with my series Signs, both from the early ’90s. But I am glad I never took heed, because art is about challenging and changing dominant cultural hegemony. I feel the same way about Cahun’s work. She has left us with these images that show how she was disrupting ideas of gender and reconstructing what identity means, which is very topical at this moment in time.

© Jersey Heritage and courtesy Jersey Heritage Collections

Cullinan: Can you share with readers a bit more about how this exhibition has taken shape, particularly your research trips to Jersey, where Cahun lived for the last twenty years of her life, and your curatorial involvement and “collaboration” with Cahun in the new works you are making for it?

Wearing: The exhibition has really brought me much closer to Cahun’s work and to her life. By going to Jersey with curator Sarah Howgate from the NPG, I saw the house where she lived, which was next door to the church where she was buried, which was next to the beach where she walked her cat on its lead. It was so unusual to have such a huge part of someone’s life in this small area of land. I was able to imagine those portraits of her being shot on the beach, at the cemetery, or on the wall of her garden, and from that create my own idea of her biography as an artist. Also, the Jersey Heritage Trust has the largest collection of Cahun’s works, many of which we have borrowed for the exhibition. The whole trip was a real treat, this tiny island with a treasure trove of this great artist’s life and work.

Nicholas Cullinan is the director of the National Portrait Gallery in London, where Gillian Wearing and Claude Cahun: Behind the mask, another mask will be on view from March 9 to May 29, 2017.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.