How a Xerox Became a Time Machine

By using a copier to reproduce other artists’ photographs, Aaron Stern raises questions about authorship, circulation, and the persistence of the printed image.

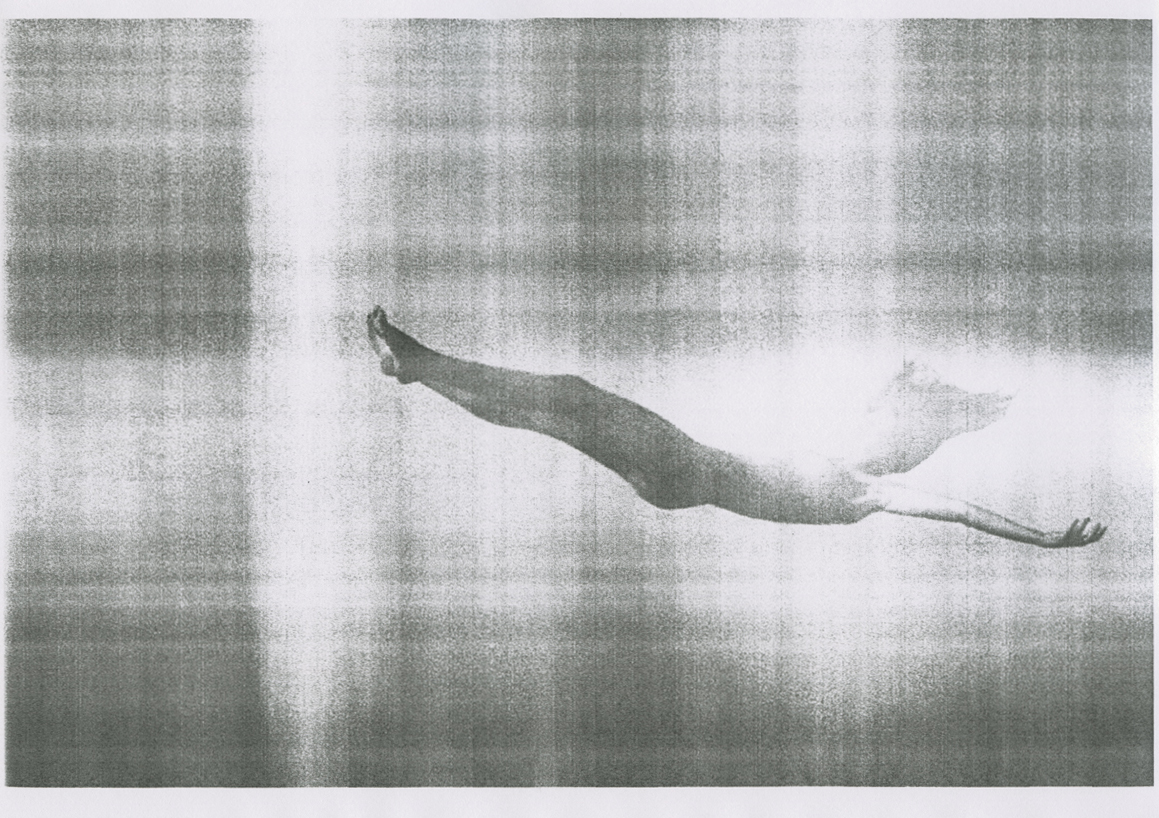

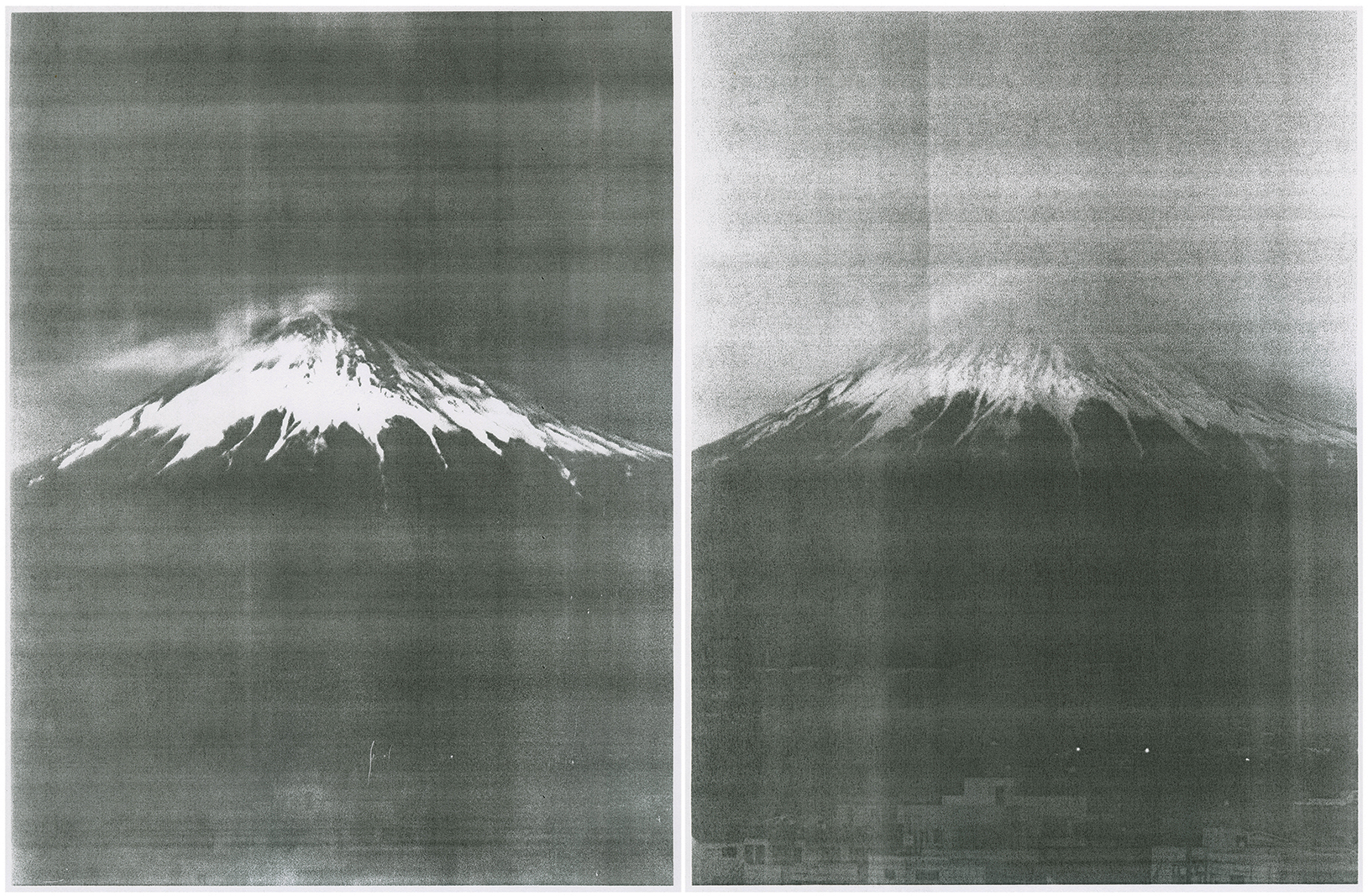

Asako Narahashi, Kawaguchiko #2, 2003/2025. Photocopy by Aaron Stern

© Asako Narahashi

Aaron Stern is an artist and curator who has long been fascinated by alternative modes of printing photography. His latest foray into exhibition-making, Hard Copy, is currently on view at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York. The show is a study of a dated process: toner seared onto paper, images recycled through old copy machines, photographs we often see on screen rendered tactile again and taped on the wall.

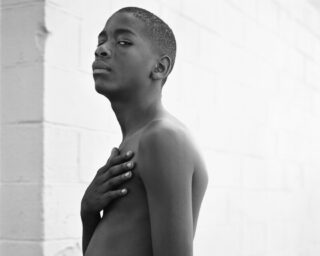

But Hard Copy is equally concerned with aesthetics as it is with friction—between reproduction and originality, circulation and authorship, intimacy and scale. Stern’s appropriations and translations of works by artists like John Divola, Ryan McGinley, and Shaniqwa Jarvis show how images accrue meaning not despite their reproducibility, but because of it. As David Campany, the cocurator of Hard Copy New York, notes, “With Hard Copy given proper gallery space alongside shows of framed contemporary and canonical vintage work, the photocopied image feels both welcome and like an intruder.”

When Hard Copy Los Angeles was on view last year in LA, I spoke with Stern about his long-standing fascination with Xerox as a medium and how the democratic nature of copy machines continues to bring new understandings of images we know and love.

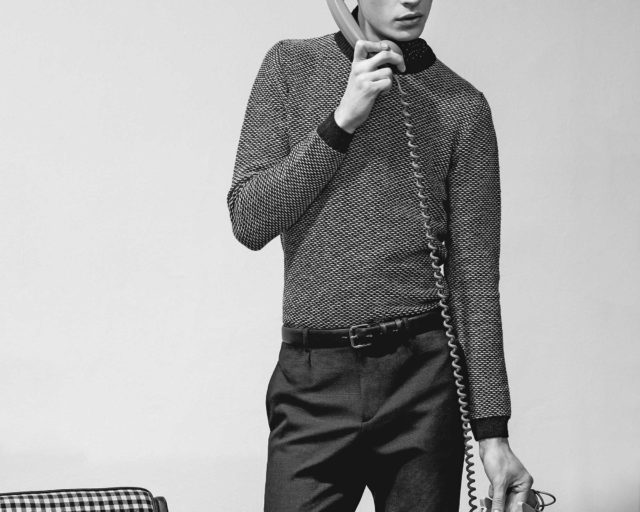

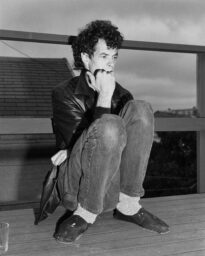

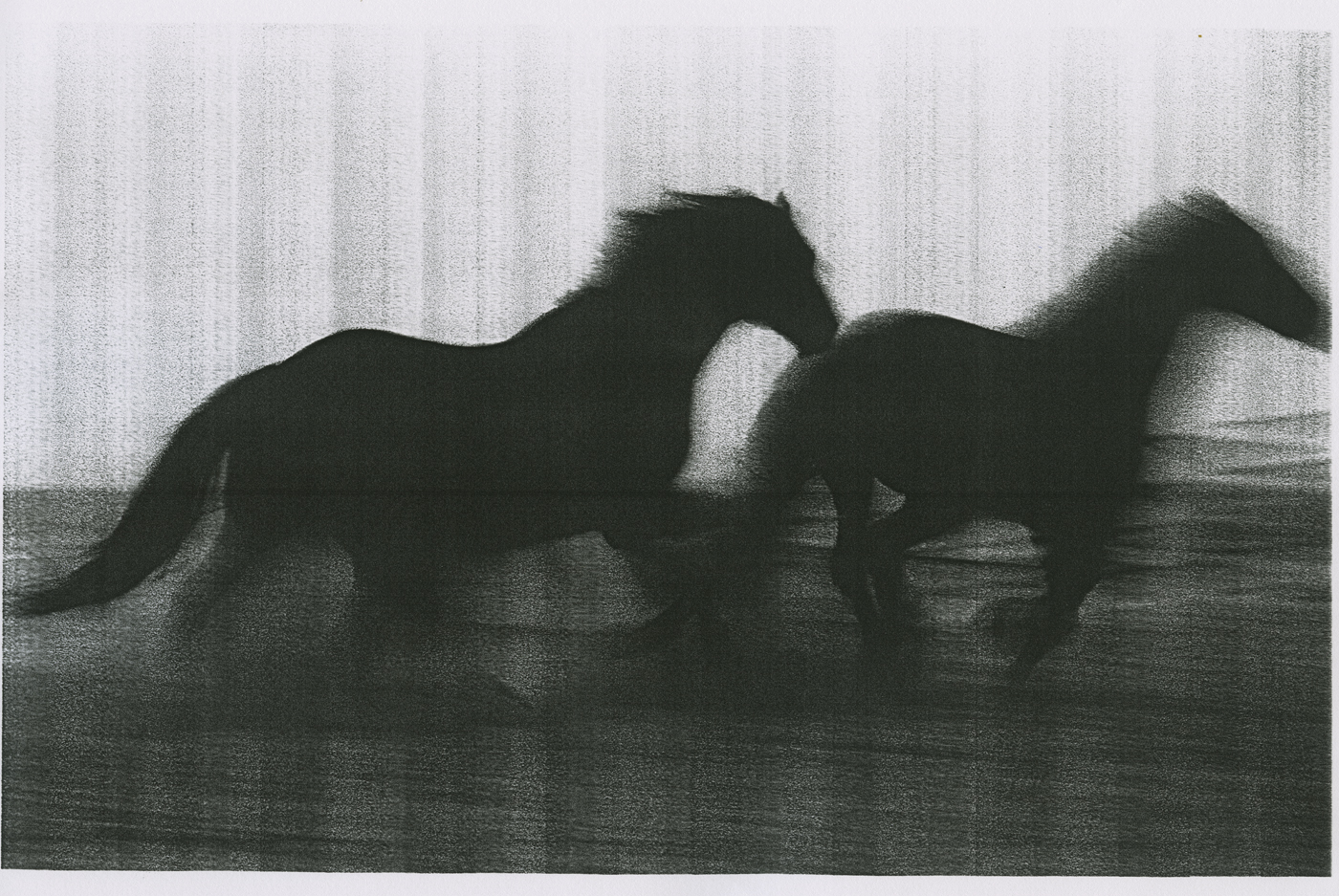

© Ryan McGinley Studios

Noa Lin: Why Xerox? What got you thinking about this form?

Aaron Stern: I did a book with Lucy Helton and Twin Palms called OK, No Response (2021) where we would exchange images between us and other artists through fax machines. But before that, I used to have a laser printer in my studio, and I used to make homemade zines.

My first two books were printed offset, with a year of planning and book design and all that. It’s a great process, and I learned a lot. But it’s hard. It’s a really long process, and sometimes you want to make something quick, where it feels more in the moment. With a zine, you can just print something and make ten copies and do it overnight. I mean, I made the zine for Hard Copy LA, and it usually takes me a month to design a book, and I did it over the weekend. It was a lot of fun.

I’ve always been a fan of artists like Raymond Pettibon, Richard Prince, Wolfgang Tillmans, and David Hammons. I love all of the postcard art that Cy Twombly and all his contemporaries would send to each other. I love public art, and I like the idea of something that’s not so precious. There’s a sense of flexibility, trial and error, experimenting, bending the rules, and doing things that sometimes might ruffle feathers. It goes against a pretentious idea of art, not necessarily to piss people off, but just to mix things up.

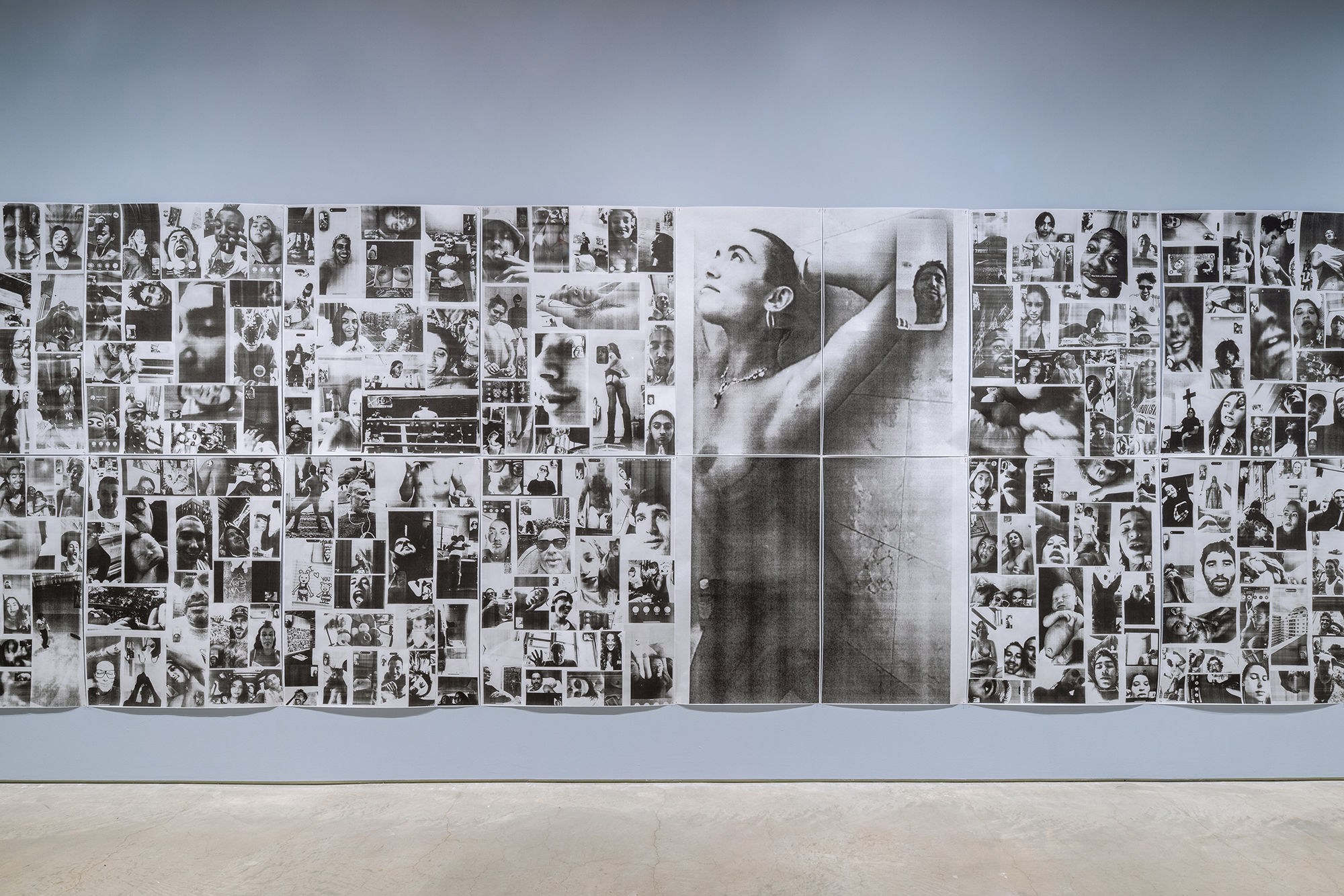

Courtesy the International Center of Photography

Lin: I was curious about how you’ve been thinking about Xerox in today’s art world. In the wall text for the Hard Copy LA exhibition, Xerox is likened to craft, in opposition to the flood of digital imagery we find on the internet today. But that’s sort of an interesting logic for me. In its own way, Xerox has had a connotation of being infinitely reproducible, a cheap facsimile, with easy means of distribution, no?

Stern: I think that’s an interesting point, but I think that people don’t make Xeroxes anymore. I think maybe twenty-five, thirty years ago it was used by corporations and lawyers and people to make mass amounts of documents to pass around. But most things are digital now, and I don’t think that’s the case any longer.

Photography is a powerful art form, but it rarely gets shown. And photography galleries are closing and showing less photography. I think that’s just because everyone has an iPhone and can take a picture.

When I first started taking pictures, I was taking pictures of music. A lot of my friends were in bands, or they were managing bands, and they gave me photo passes. I wanted to be out and listening to music, so I used it as an excuse to shoot them. I’d be down in the photo pit for the first three songs and then was on the side of the stage, and it was cool. Then one day, the iPhone came out, and I turned around and everyone was taking pictures right behind me. And I realized my picture was irrelevant because everyone can take it. And if you see that picture, it just reads as, Yeah, you were at a concert. It loses its power.

I think that’s the case with everything, sadly, but it goes both ways. It’s amazing that I can take a picture with my phone and send it to the mechanic about something in my apartment that’s broken. But at the same time, the individual power of an image loses its strength. Also, you’re only seeing images on this little screen all the time. I wanted to create something that was big and impactful and would give people a different experience.

© Shaniqwa Jarvis

Lin: Between the meticulousness of a fine art print and the immediacy of digital, what is it about Xerox that holds that middle ground for you?

Stern: It’s the aesthetic. It’s the way it looks. But it also gives me the ability to experiment inexpensively. I can make thirty copies of something and get it right for the cost of a dollar. The experimentation really opens a lot of doors in terms of being able to get something to look the way you want, without having to sit in front of a computer for several hours.

It also gives you the ability to make something consistent across many artists and build a concept out yourself, which is both fun and a challenge. I remember the first time I was showing my own work; it was a month of back and forth with the printer to get eight prints right. It was tough. Sort of like making an offset book: You get a wet proof, it doesn’t look right, you send it back, they send it back again. It’s months of work for something, but Xerox is totally opposite of that.

Lin: Yeah. It’s very DIY. Like you said, it gives you the space to really experiment without spending so much money, or having to deal with separators, or paying for some lab to help you.

Stern: I think it’s less about the money and more about doing what I want to do without having roadblocks. For example, being able to experiment until two in the morning by myself. I like being hands-on, and fax and Xerox and all that technology is really accessible. I also like the idea that it wasn’t meant for this purpose.

Courtesy the International Center of Photography

Lin: It looked like some of the prints were pretty big. How are you thinking of scale?

Stern: They’re very big, yeah. It was fun to experiment and figure out ways of problem-solving and making things bigger. The original idea was for me to just appropriate lots of people’s work and make the show just of my work, like the Thomas Ruff pictures, the thumbnails of porn that he appropriated. I wanted him to be in the show, and then that’s what sort of gave me the idea. But as I was talking to a few friends, I thought it would just be a lot more fun to do it with the photographers and artists together. And it was.

Lin: Yeah, there’s something collaborative about that that I feel plays well with Xerox and copy machines. For example, in OK, No Response, the method of making are these correspondences that happened over fax.

Stern: Definitely, and it was fun. Some photographers in the show were in my apartment together, and we were hanging out and bouncing ideas off each other. We were getting ice cream at 10:00 p.m. and then coming back to work on it more. That was a really fulfilling experience.

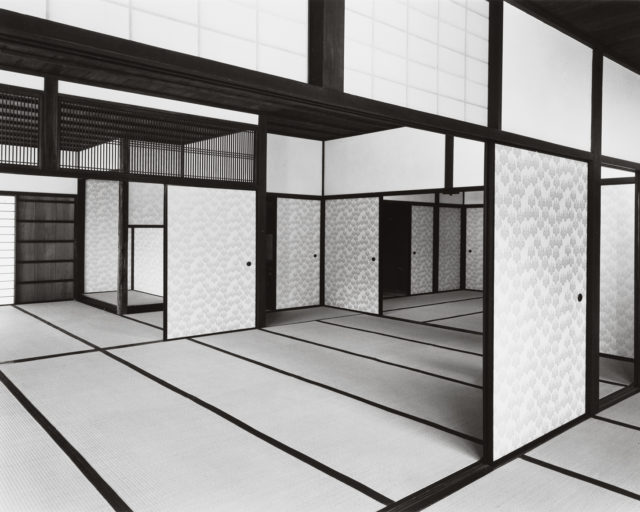

© Takashi Homma

Lin: Was the history of Xerox and art—protest materials, DIY culture, zine-making, all of that—were those kinds of considerations in your mind? How did that inform your thinking?

Stern: Well, I was definitely thinking about it in terms of why I wanted to do it. It was definitely in the back of my mind. In choosing the people that were in the show, not so much. After doing the fax book, I kind of got an idea of how certain work would render after being reproduced on a fax. So that was sort of my theory, my process of it.

Lin: What was the aesthetic that you found in people’s images that you thought would translate well to Xerox? What were you looking for?

Stern: I knew who I wanted to work with because they’re people I’m close with, and other people in the show are people that I’ve always wanted to do something with. It was more about them and then finding a work that would translate well as a Xerox. And then there were certain pictures by people I knew that I wanted to have in the show because I knew that they would work well as a Xerox, so it wasn’t so strategic.

I met Jeff Wall ten years ago, and we stayed in touch over email a bit, and I just always was waiting for the right thing to ask him to be part of. I thought this was a good opportunity for that. Here’s an artist that shows in museums around the world, and I think it’s a non-precious, not-for-sale, punk thing to be part of. I just had a feeling that he would get it, and he did, and that was really cool to have him see what I was doing and want to be in it. He doesn’t need to do this, but it was fun to go back and forth with him over email. Same with Takashi Homma. He was the first person I thought of. I knew that the Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji would look great xeroxed.

Lin: So, this is really a work of translation on your end—identifying artists and works, and then creating these Xeroxes of certain pieces.

Stern: Yeah, exactly.

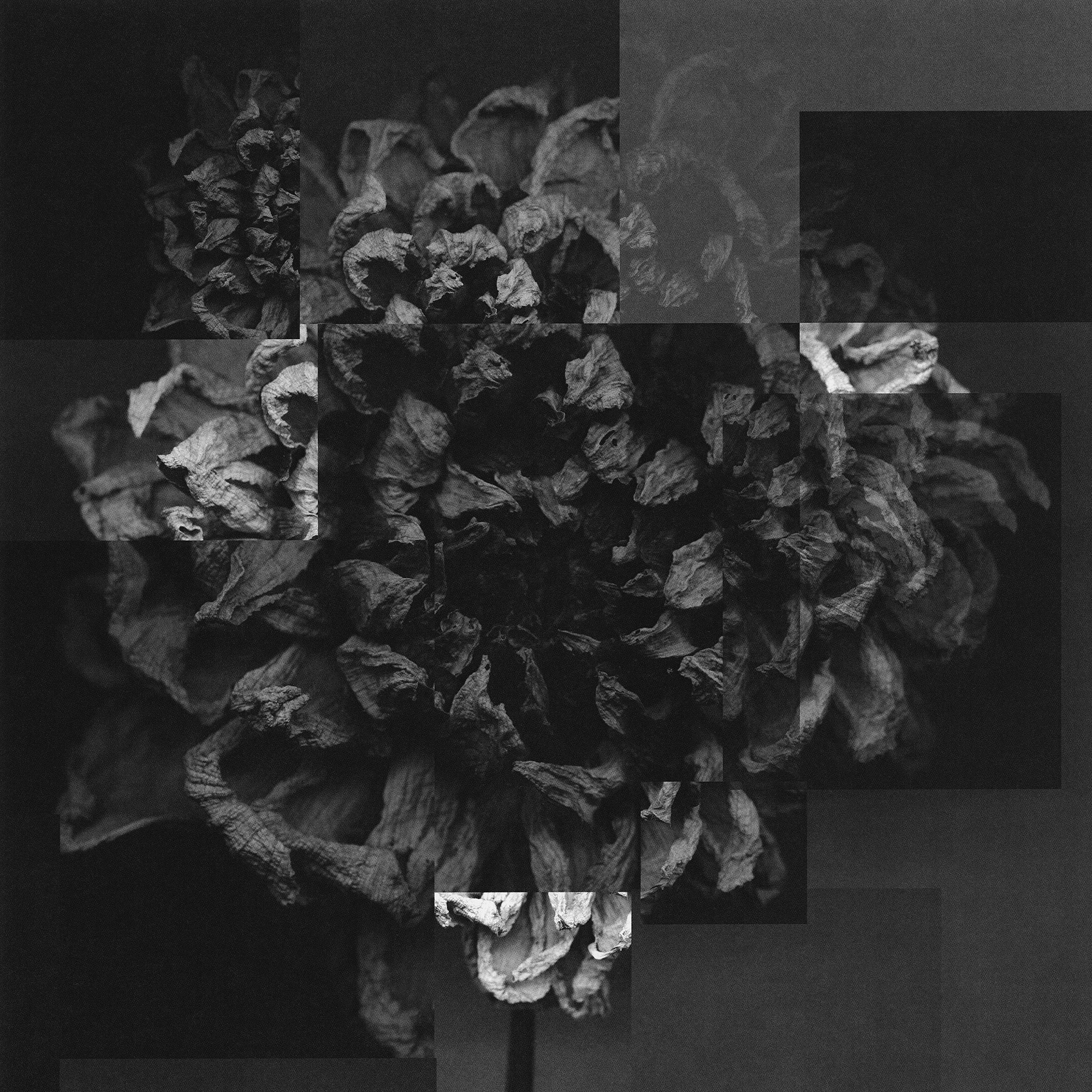

© John Divola

Lin: The show includes both established and emerging photographers. Can you speak to your thinking behind an intergenerational selection of artists?

Stern: I think it’s cool to have older, established photographers with younger, emerging photographers. You want to inspire people to be in the show that are younger, because it makes them feel good to be in a show next to someone that maybe they look up to. For an older artist, I think it’s cool for them to be in a show with younger artists because younger artists and a younger audience learn about their work. I think it benefits both. There were people that I’ve always had in mind that I knew I wanted to show, young and old.

Another thing is you need a lot of money to show 30-by-40-inch John Divola prints. Or anyone’s prints. It costs a lot of money to make C-prints and to frame them. And it takes a lot of time to do that. You need a solid three months to print and frame, and get it right, at the minimum. And this was a great way to show people’s work that I like without having to do that.

Lin: Many of the exhibitions you’ve curated engage with nontraditional or ephemeral print media. What draws you to these forms as a curatorial focus?

Stern: I think some of it is about that barrier of entry and the challenges of thinking: I want to do this, and I don’t want there to be a roadblock. Something’s too expensive, or it’s too expensive to ship, or it takes too long to make. Those are all big roadblocks in wanting to show photography.

Someone said to me when I first started taking pictures, Photography is about problem-solving. I’m a good problem solver. Both shows were a challenge. How can we do this on this budget, with this amount of time, in this location? And how are we going to make it great?

That’s sort of the idea behind the show. Figure out a way to do it yourself, and experiment and make it look the way you want to look. It takes down this barrier of entry.

Lin: Totally. Anyone can do it if they have a copier or a fax machine or home printer.

Stern: Yeah, and a good eye and some taste.

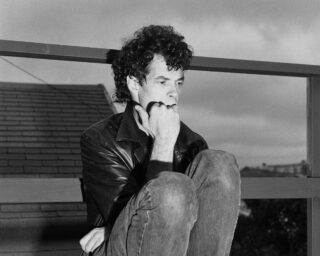

© David Black

Lin: What, if anything, is different between Hard Copy Los Angeles and this iteration at ICP?

Stern: The ICP gave me what I have never had before: a cocurator in David Campany, and a full team of support. This all translates into a cleaner, more focused version of Hard Copy.

Ari Marcopoulos being included felt different as well, as the show is partially inspired by his book, The Chance is Higher (2008). Having artists like Collier Schorr, Ryan McGinley, and Stephen Shore in the show is important, too, as all three were artists I looked to when I was starting my career. Thomas Ruff’s work being represented also felt like a full-circle moment. His Nudes series was the first work that I xeroxed when I started experimenting for the first version of Hard Copy in early 2024. I had reached out to David Zwirner to include his work in the first two shows, and unfortunately it didn’t happen. With David Campany’s help, this time we were finally able to include him.

I’ve always felt like a bit of an outsider in photography. For the last fourteen years, I’ve scrapped together exhibitions with razor thin budgets and hustled to try and show work, whether it be in a book or exhibition. As someone who’s self-taught, with a nontraditional background, curating a museum show like this is a huge thing.

Hard Copy New York is on view at the International Center of Photography, New York, through May 5, 2026.