India in Full Color

Raghubir Singh, a protégé of Henri Cartier-Bresson, captured the fleeting beauty of twentieth-century India.

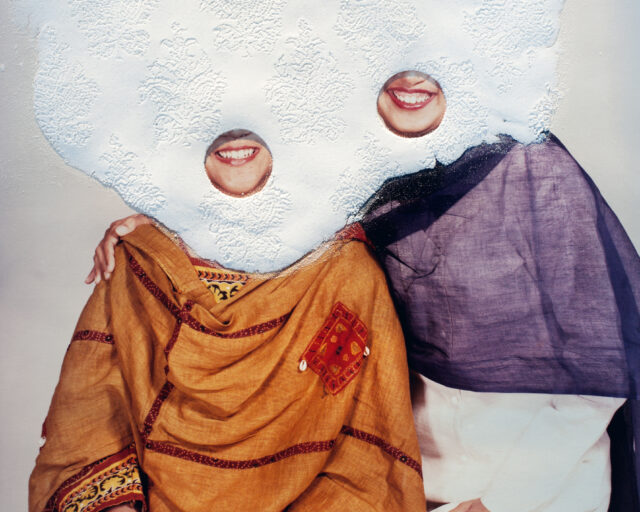

Raghubir Singh, A Marwari Wedding Reception in South Calcutta’s Singhi Park, Calcutta, West Bengal, ca. 1972

© Succession Raghubir Singh

In 1999, when photographer Raghubir Singh died of a heart attack at the age of fifty-six, his work was being shown at the Art Institute of Chicago in what was intended to be a midcareer survey. He had spent his adult life living in Hong Kong, Paris, and London, but his photography, which is now the subject of Modernism on the Ganges, a comprehensive retrospective at the Met Breuer, maintained a focus on his native India. The thirteen books he published over the course of three prolific decades—a fourteenth, which took the Indian-manufactured Ambassador car as its subject, was released posthumously—were organized geographically and helped push color photography from the fringe of the art world to the center. Together, these projects form an inimitable map of Indian culture, drawn in the vivid hues of Kodachrome, and mesh modernist photography with Indian aesthetic traditions.

© Succession Raghubir Singh

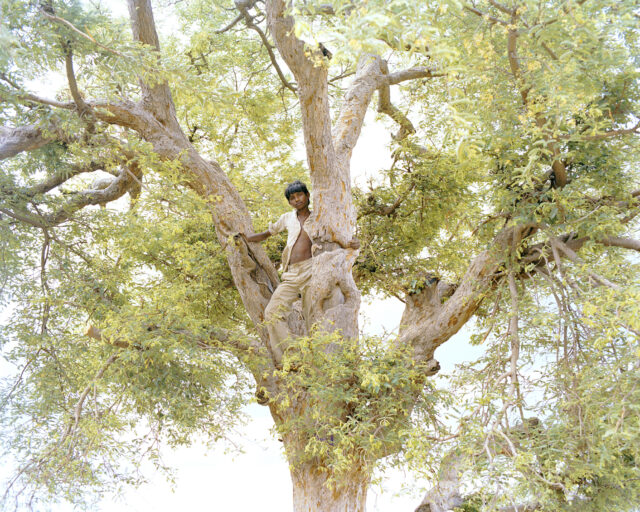

Space collapses and divides itself in Singh’s photographs, and his compositions move with speed from men and women to painted and sculpted figures, to animals, to cars, and across landscapes. In some of his earliest pictures from Calcutta (now Kolkata), people on the street sink into visual arrangements, as do a statue of Subhas Chandra Bose and a mural featuring Vladimir Lenin. Similarly, in a 1991 photograph from Bombay (now Mumbai), three mannequin figures appear like members of a crowd at the Ganapati Festival. Singh held a deep admiration for Henri Cartier-Bresson and, in his early twenties, had what must have been a formative opportunity to spend a few days with the French photographer in Jaipur. Like Cartier-Bresson, he had a keen eye for striking visual parallels: a man’s net seems to take up a statue of a lion at the Victoria Terminus in Bombay; a cockeyed green door reframes a monument.

© Succession Raghubir Singh

In front of Singh’s lens, bustling scenes look like carefully arranged collages. The effect can be playful or ironic, but his attention to marks of the past tie each image to a place. The reflective surfaces that appear in many of the photographs are not just an opportunity to make pictures-within-pictures, but also “suggest a future not the past,” as he told the writer V.S. Naipaul. Images with multiple focal points pack frames to capacity. Instead of avoiding visual incongruity, Singh embraces it: in a 1986 photograph from Calcutta, a split-screen effect separates household employees from the gathering that they watch. Singh composites signs of India past and future, disparate political ideas, and varied moods in a single frame.

© Succession Raghubir Singh

These same techniques allowed Singh to work in dialogue with of a wide range of artists, among them Helen Levitt, Lee Friedlander, Eugène Atget, and Ketaki Sheth. Such photographs punctuate Singh’s work on the walls at the Met Breuer. Hung among his projects are several Indian court paintings, images by other street photographers like Friedlander (whom Singh considered “the master modernist” of his time), vast landscapes of nineteenth-century British colonial photographers, and hand-painted studio portrait photography from the early twentieth century. In two comparative juxtapositions, Singh’s photograph of Holi revelers in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, from 1975, is joined by Cartier-Bresson’s depiction of dozens of refugees in Punjab, from 1947; and an eighteenth-century watercolor mirrors Singh’s photograph of two girls in Hathod Village, Jaipur, cutting through monsoon-season heat on a high-flying swing.

© Succession Raghubir Singh

As Singh saw it, Indian culture, with its central ideas about “the cycle of rebirth, in which color is not just an essential element but also a deep inner source” could not be coded in black and white, with its artistic modes built on the Western associations of black with “guilt, linked to death.” His undertaking required color. Novelist Amit Chaudhuri writes in the accompanying catalog that Singh’s self-assigned task as an artist was “to find a way of accommodating the joy that his cultural formation in Rajasthan gave him within modernism’s fragmentariness, its openness to texture and sensation.” This meant avoiding abjection as a subject, and opting instead to communicate what Singh called the “lyric poetry inherent in the life of India.” This accomplishment does not arrive forcefully in images that seem patriotic. Nor does color pop with oversaturation. His search for joy deals in subtleties, which allows for his photographs to appear fresh decades after they were made.

© Succession Raghubir Singh

In conjunction with Modernism on the Ganges, Howard Greenberg Gallery recently opened an exhibition of Singh’s photographs from Bombay: Gateway of India (1994). In Singh’s Bombay, his interest in a changing India, which can function more as subtext in other projects, sits on the surface of the images. We see the city in the early ’90s, with its eyes turned directly at globalization. The scenes are some of the most urban in Singh’s work, and, as Chaudhuri writes, “Bombay shows how one might desire to surreptitiously linger in and inhabit the places we visit in the time of globalization.”

© Succession Raghubir Singh

While researching the exhibition, the curator Mia Fineman learned that when you were with Singh on the street, you could see his eyes marking out the four corners of frames-to-be. Modernism on the Ganges helps us begin to imagine the index of images—the worldview—that Singh used to orient his own work. And, perhaps more importantly, it highlights the humanism he maintained while taking up all of India as his material. As the art historian Partha Mitter writes in his essay for the catalog, Singh “saw himself as an Indian, with deep roots in the land.” Whether borrowing compositional forms or taking innovative steps in his use of color, working from the influence of Cartier-Bresson or Indian paintings, photographing on the street or making a formal portrait of a writer, he was, as Mitter puts it, “on a quest to delve into the inner source of India’s art and culture, its moral foundation.”

Modernism on the Ganges: Raghubir Singh Photographs is on view at The Met Breuer through January 2, 2018.