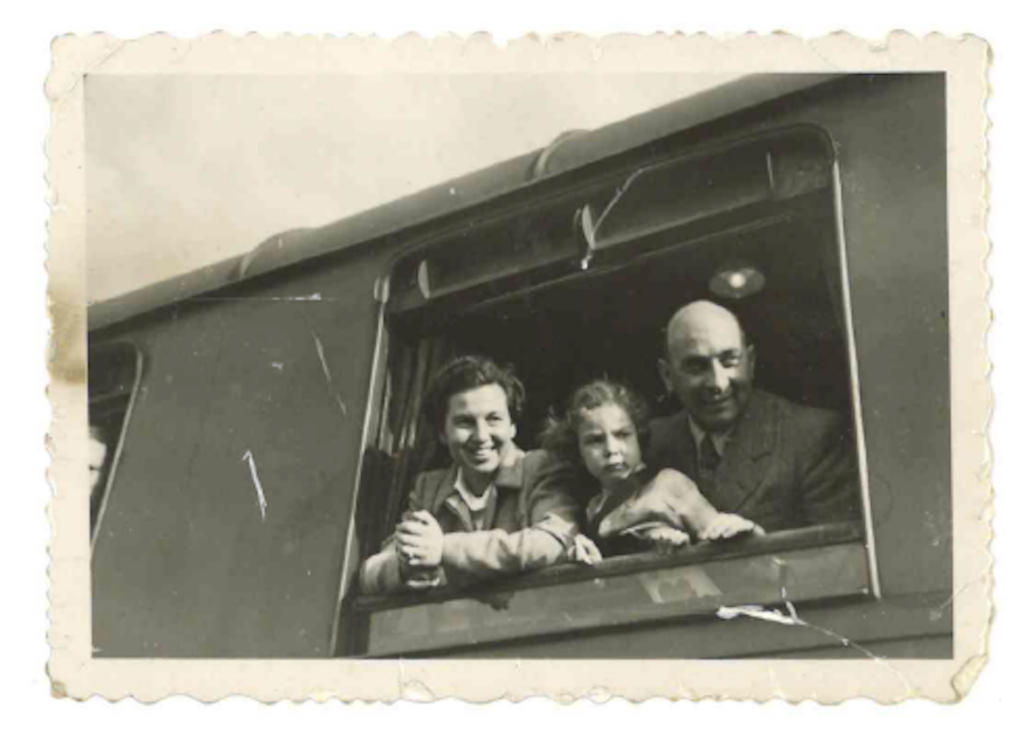

Malcolm with a camera, date unknown

“Taking a picture is a transformative act,” Janet Malcolm once wrote. As photography critic for the New Yorker from 1975 to 1981, she developed an understanding of the camera not as a mirror—that naïve, and now passé belief that photographs simply reflect reality—but instead as a light source: illuminating, even coloring, and leaving plenty in the shadows. “The images our eyes take in and the images the camera delivers are not the same,” she reasoned. An artist herself, with collages and photographs exhibited and published, she was practiced in the ways the lens can transform.

Malcolm’s critical view is not Susan Sontag’s charge of photography as aggression; nor is it Roland Barthes’s dirge for what is no longer. Malcolm, who died in 2021, was drawn to the form for its confounding potency and evasive, expansive nature, particularly in quotidian images like the snapshot. She was interested in the chasm, not only between the eye and the camera, but between the images our eyes take in and what we later recall. Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory, published posthumously at the beginning of this year, shows a writer drawn to the photo as it relates to memory, the ultimate object of Malcolm’s suspicion.

Family photographs are a way into personal writing for Malcolm. Through the twenty-six vignettes that form Still Pictures, she follows almost as many images toward memories and associations that together form a life in snapshots. A portrait of Malcolm’s mother as a girl; neighbors and friends of her parents; “my bad-girl friend Francine”; a scene from Camp Happyacres; a family trip to Atlantic City; Malcolm grinning with her husband; Malcolm looking writerly in the 1990s, around the time she saw a speech coach to prepare for a libel lawsuit against her—these are just some of the images that “stir” Malcolm to remember.

Born Jana Klara Wienerova to a Jewish family in Prague in 1934, Malcolm and her family fled Nazism in 1939, and by the next year were living in a Czech neighborhood in Yorkville on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Still Pictures includes tender moments and instances of Malcolm’s love of the absurd, a humor inherited especially from her father. One of two opening pictures shows a tiny Malcolm, age two or three, sitting on a step, her hands on her knees in an “assertive pose” that she finds interesting but that she cannot identify with. “If I were writing an autobiography, it would have to begin after the time of that photograph,” Malcolm writes. “My first memory dates from several years later.”

Consummate eye-narrower and precise observer, Malcolm is perhaps best known in her writing for her authoritative persona and interrogation of the official narrative. Throughout a long career, she drew attention to the ways in which writing and reporting can be not only acts of transformation, but hostility. The opening of The Journalist and the Murderer—“Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible”—is one of the better-known sentences in literary nonfiction (and though at first one of the more controversial, many now consider it conventional wisdom). And while Still Pictures treads some of this familiar territory (“Do we ever write about our parents without perpetuating a fraud?”), in her last book Malcolm flirts with the possibility of doing what she vowed she never would: autobiography.

“I cannot write about myself as I write about the people I have written about as a journalist,” Malcolm explained in 2010. “No one is dictating to me or posing for me now.” Through old family photos, Malcolm finds many a willing model, most of them conveniently dead. It is an appropriately oblique way in for a writer who saw autobiography as “an exercise in self-forgiveness,” as opposed to her unforgiving—and, according to Malcolm, unforgivable—work as a journalist. Photos allow Malcolm to make her way toward personal writing, but at times she still cheekily refuses to play. Recalling an ornate Italian plate she bought long ago to use in an apartment where she met the lover who would later become her husband, Malcolm writes: “What did it mean to me? Why did it come to mind after so many years? I know the answer, but—like a balky child—I find myself reluctant to give it. I would rather flunk a writing test than expose the pathetic secrets of my heart.”

The creation of an honest former self always gave Malcolm serious pause. “Not only have I failed to make my young self as interesting as the strangers I have written about, but I have withheld my affection,” she noted in 2010. Critics have appraised the efficacy of Still Pictures as memoir (though apparently Malcolm did not characterize the essays as such), including Vivian Gornick, who wrote in the Nation, “After reading the collection, I felt obliged to agree with her. Malcolm does withhold affection from her long-ago self, and as a result the most important element in memoir writing—a satisfying persona—is missing.”

And yet, despite or because of this, in Still Pictures Malcolm follows memory’s lead—as if “simply by going with the camera instead of against it,” as she wrote in 1978 to describe when “photography went modernist.” The book could be said to mimic memory’s natural, often unsatisfying rhythms, embodying its inconsistencies, whims, repetitions, and blind spots. If Malcolm is a memoirist at once seduced and repulsed by memory, Still Pictures is a memoir that takes memory’s artistry as both muse and captor.

Photography finds itself a partner to this reluctant but inspired tango with the past. “Most of what happens to us goes unremembered,” she writes. “The events of our lives are like photographic negatives. The few that make it into the developing solution and become photographs are what we call our memories.” And yet, “Occasionally… like memory itself, one of these inert pictures will suddenly stir and come alive.” A memoir-in-snapshots may be the only form up to the task of “memory’s perversity.”

Though she never fully trusts memory to tell a good story, the sharp-eyed critic and journalist manages a memoir-in-snapshots by looking.

The book’s formal conceit could seem an apt conclusion to a fifty-five-year, career-long preoccupation. “People tell journalists their stories as characters in dreams deliver their elliptical messages,” Malcolm wrote in The Journalist and the Murderer, “without warning, without context, without concern for how odd they will sound when the dreamer awakens and repeats them.” In Still Pictures: “as psychoanalysis has taught us, it is the least prepossessing dreams, disguised as such to put us off the scent, that sometimes bear the most important messages from inner life. So, too, some of the drab little photographs, if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us.” At the end of her writing life, Malcolm was as skeptical as ever about our ability to interpret our own lives. And yet, as both dreamer and journalist, she attempts to parse hers.

One vignette, titled “Lovesick,” was stirred by an image of a group of high-schoolers found in a box in Malcolm’s apartment labeled “Old Not Good Photos.” The number of times throughout the book Malcolm refers to love as a sickness, a virus “for which there is no vaccine,” a habit, a contagion, is striking. Letting her narratorial guard down briefly, she revels, almost childlike and at times approaching cliché, in life’s inexplicable timing and force, the elusiveness of what remains. Though she reports boredom at the randomness of what’s lost and what’s retained by memory, Malcolm was also clearly fascinated by the mystery, the art of it. Of her own collages, she once wrote to a colleague, “There does seem to be something occult going on here, and I don’t think I believe in the occult.” This tension is felt throughout Still Pictures.

In the introduction to Diana & Nikon, a 1980 collection of her photography criticism rich with literary reference, Malcolm describes the medium as at once fascinating and baffling—“Defying anyone to say what exactly its place in the arts is. The force of this singular orneriness is felt by every critic of photography and gives writing about photography its own peculiar atmosphere of unease and uncertainty.” Photography’s reputation as untrustworthy—elusive, even suspicious, implicated—would congeal during and after Malcolm’s days as a photo critic. (The title’s “Diana” refers to a plastic camera meant for hobbyists but taken up by artists such as Nancy Rexroth and Jo Ractliffe.) Decades later, in Still Pictures, Malcolm seems to trust the famously compromised medium to explore something more spacious than fact, some greater truth about time, subjectivity, and memory.

All photographs courtesy Janet Malcolm

Malcolm’s reliance on pictures from everyday personal collections allows for an intimate excavation of the chief concern of her photography criticism, after the medium’s relation to painting: how the artform was influenced by utilitarian uses of the camera like the snapshot. This was long before democratization via the smart phone, but around the time of the invention of the digital camera, a boon for amateur photographers. In the final vignette of Still Pictures, “A Work of Art,” Malcolm reveals that alongside her title essay in Diana & Nikon, which discusses the “deliberately artless photography” collected in Aperture’s Fall 1974 issue, “The Snapshot,” she snuck in an “outstandingly terrible snapshot” of a couple on a tennis court that her husband kept as a joke. That this random photo was printed without question alongside photographs by Rexroth, Joel Meyerowitz, and Robert Frank, inspired great delight in Malcolm.

A playful yet serious interest in authenticity animates Still Pictures. Who is the authority on our own lives? Malcolm had her answers and, daring finally to turn the lens on herself, she answers anew. Though she never fully trusts memory to tell a good story, the sharp-eyed critic and journalist manages a memoir-in-snapshots by looking, a skill long honed; then she follows memory, the ultimate absurdist artist.

Janet Malcolm’s Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory was published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2023.