Speak Loud and Embrace the Protest

© Luis C. Garza and courtesy the photographer and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

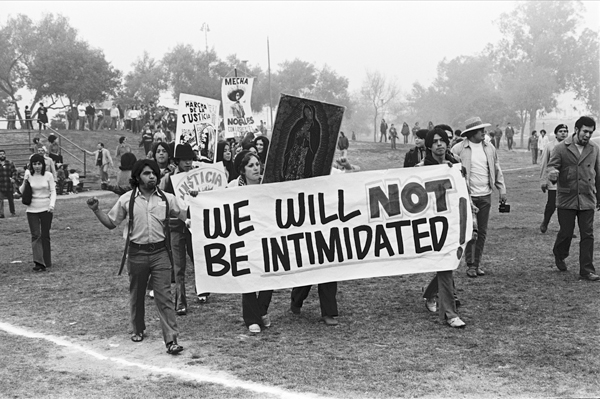

An image of a Latina yelling into a microphone while raising her fist marks the entrance to LA RAZA, an exhibition of Brown Power photographs currently occupying the ground floor of the Autry Museum of the American West, with the boldness of a late-1960s Chicano Blowout. LA RAZA (“The Race”) celebrates the boundary-smashing photography of the activist newspaper and magazine of the same name, which was published in East Los Angeles from 1967 to 1977. In each of the exhibition’s thematic suites are stunning images of protesters waving signs that say Aztlán es mi Tierra, police officers aiming weapons into the infamous Silver Dollar Bar and Café, and the resplendent Latina demanding that her voice be heard.

Why is it shocking to see Brown history here?

© La Raza staff photographers and courtesy the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

The Autry Museum has not always been first on the list of Latinx-friendly art venues. Founded in the height of the Reagan Era, the Autry is named after Gene Autry, the famous “singing cowboy” star of such history-erasing insults as 1939’s South of the Border and the 1940 classic Gaucho Serenade. The Autry’s nerve-rattling exhibits of Manifest Destiny romanticists like W. H. D. Koerner once earned the museum a boycott by the American Indian Movement in 2001: “Indians are not for sale,” AIM said.

Hope arrived in the form of the Autry’s current director, Rick West, who helped found the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), and is a citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Nation of Oklahoma. West has initiated a host of inclusive programs, including shows of Pomo basket maker Mabel McKay, Wiyot artist Rick Bartow, Chicano photographer Harry Gamboa Jr., and the Aztlán-tastic photo-feast that is LA RAZA.

© Luis C. Garza and courtesy the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

A bit of digging reveals that the Latina yelling into the microphone is Celia Luna Rodriguez, the 1970s leader of the Barrio Defense Committee. The photograph, taken by Luis C. Garza, then a staff photographer for La Raza and now an independent curator who co-organized the show, is a heady mix of star-making charisma and community solidarity. Garza’s black-and-white image situates Rodriguez dead center, in the midst of an outdoor crowd; a film camera at the bottom left corner shoots out a ley line of pure energy that leaps toward Rodriguez and up to a few observers perched high on rooftops to see her better. This icon of Latina political leadership was culled for La Raza out of more than twenty-six thousand images that Garza, as well as Maria Varela, Pedro Arias, Manuel G. Barrera, Raul Ruiz, and others, took during the publication’s all-too-short run.

LA RAZA brings back all of those exciting and harsh memories from the late 1960s and ’70s, when Latinx students exited their LA high schools en masse in order to protest unequal education. On the Autry’s floor spreads a relic of what became known as “blowouts.” Visitors to the exhibition step over an enlarged copy of a photo of a sidewalk sprinkled with pine needles and the spray-painted phrase WALK OUT. Up on the walls, in both enlarged, back-lit images and black-and-white prints made from the original negatives, a bouffanted lady gets hauled off by a tall white man, next to a fallen sign reading Viva La Raza. A squad of brown-bereted women takes back the streets in matching trench coats and black pants. A tiny, hollering Chicanita in pigtails grasps copies of the newspaper, whose banner headline reads La Raza Raided.

© Maria Varela

But it’s the photographs of the Chicano Moratorium March, which took place in LA on August 29, 1970, that really tear into old wounds. The march was led by Chicano rebels who protested the Vietnam War, but the peaceful walkers who set out from Laguna Park were met by hundreds of helmeted police from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s office. Soon, physical clashes between the activists and law enforcement sent shocks through the crowd, and the melee deteriorated into a frenzy of tear gassings.

Watching the fracas was Ruben Salazar, the Chicano columnist for the Los Angeles Times and a director of the Spanish-language TV station KMEX. Soon after, he retired to the nearby Silver Dollar Bar and Café. But a police officer shot tear gas canisters into the restaurant, and one hit Salazar in the head and killed him. In LA RAZA, images on display show the police attacking the poky-looking Silver Dollar. In one photograph, an officer aims his gun at two unarmed men, while two women hold up their hands in terror. Directly above it presides the last known picture taken of Salazar while he lived. He walks down a street crowded with marchers, wearing a white shirt and longish hair. You can barely see his face.

© Pedro Arias and courtesy the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

This image and the one of Celia Luna Rodriguez form two lodestars within LA RAZA’s constellation. The exhibition has been on view during a period in contemporary history that unfortunately recalls the era of the Autry’s origins, as the current president of the United States characterizes Latinos as drug dealers and rapists, police killings of Black people continue to traumatize people of color and result in scandalously low conviction rates, and Trump now threatens to end birthright citizenship through the illegal means of an Executive Order. In such a climate, it’s hard not to feel dragged down by your losses. It’s better, though, to follow the lead of Rodriguez, as pictured so beautifully by Garza, and the exemplars of the other La Raza photographers and their subjects: we have to embrace our struggle and speak out loud our protest.

Yxta Maya Murray is a contributor to Aperture, issue 232, “Los Angeles.”

LA RAZA is on view at the Autry Museum, Los Angeles, through February 10, 2019.